A Paleoindian Grave

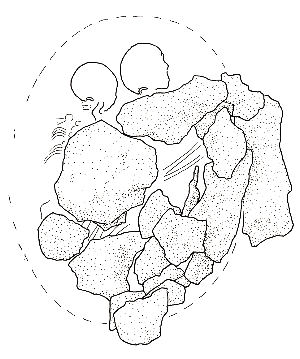

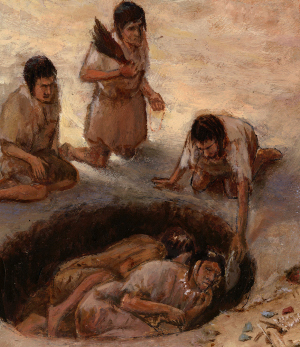

Burial ceremony at Horn Shelter, about 11,000 years ago. A group leader wearing a badger headdress shakes turtle shell and deer antler rattles as members of the funeral party place special items within the grave of the man and child. Although many aspects of this scene are based on actual archeological evidence recovered from the site, it is not intended to to be an exact reconstruction of the event, but rather one plausible interpretation of what took place in the past. Painting by Frank Weir. View full scene and details. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

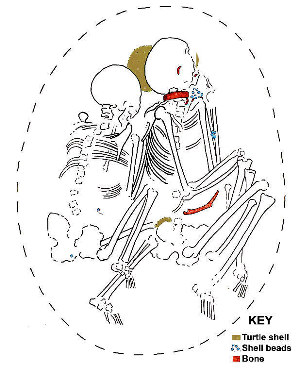

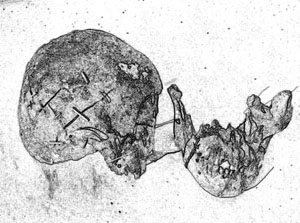

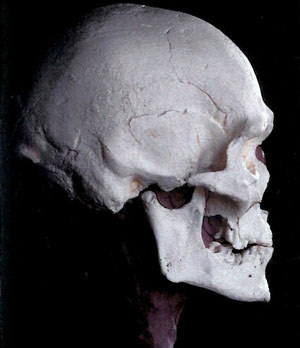

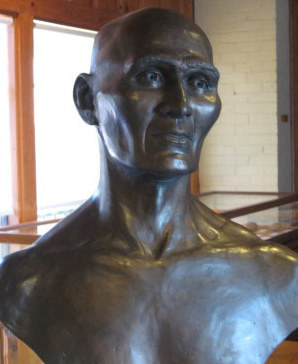

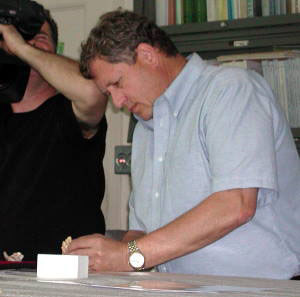

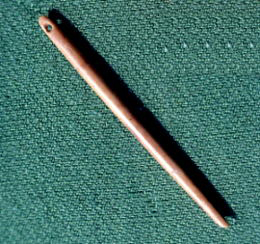

In all, more than 100 items have been associated with the burial. Notably, only one artifact, the bone needle, seemed deliberately placed with the juvenile. This finely crafted small tool may have been used for sewing, beading, or net weaving. Only one of the shell beads found near the child was unweathered; it was found between the radius and ulna, perhaps having been worn on an arm band. Interestingly, two of the unweathered beads found with the adult male were in a similar position. Certain items associated with the adult male—turtle shells, raptor talons, coyote teeth, badger claws, and exotic marine shell—may have symbolic meaning and denote high status or power. The pendants and some of the shell beads likely were strung as a necklace, armlet, or clothing adornment. A precious commodity, the shell came from the Gulf Coast, over 300 miles away. Interestingly, although the three turtle shells positioned under the man's head formed a hollow enclosure, nothing was found within. Among the most fascinating new interpretations of the burial items were of those originally thought to be a flint knapping kits. Jodry and others have suggested these, and other items, were components of a tattooing kit (hematite used for pigment; deer antler pestles for grinding the pigment in turtle shell bowls; stone biface as a source for small flakes for cutting; sharpened coyote canine for incision; and slender bone stylus for applying the pigment into the wound). Dating the DepositsRadiocarbon assays, diagnostic projectile points, and cultural stratigraphy have helped date the stratum (5G) from which the burial originated. Two charcoal samples from this layer yielded radiocarbon determinations of 9980+/-370 years B.P. (11,590+/-606 calibrated years B.P). and 9500+/-200 (10,810+/-277 calibrated years B.P.). Snail shell samples provided assays of 10,310+/-150 years B.P. (12,121+/-331 calibrated years B.P.) and 10,030+/-130 years B.P. (11,621+/-259 calibrated years B.P.). The materials dated were composite samples from Sub-Stratum 5G, that is, they were not found within feature contexts or within the burial. More recently, however, Smithsonian Institution physical anthropologist Douglas Owsley has obtained AMS dates of 9710+/-40 B.P. from bone of the adult male and 9690+/-50 B.P. from bone of the juvenile. The close correspondence of these various returns confirms the age of the burial, and validates its distinction as one of the oldest in North America. Brazos Fishtail (or San Patrice) dart points, found within the layer from which the burial was dug, as well as that below it, also point to an early time period for the burial. The base of an apparent Wilson point also was found in 5G; the remainder of this point was found in underlying layer, 5F. Both San Patrice and Wilson have been found in earlier parts of Late Paleoindian contexts at other sites, including Wilson-Leonard in nearby Williamson County. A human burial, dated between 9750-10,000 B.P, also was found at this site and is attributed to Wilson peoples. Analysis of Human RemainsDiane Young conducted initial analysis of the human remains from Horn Shelter under the guidance of Gentry Steele in 1985 at Texas A&M University. Additional analysis by Douglas Owsley is ongoing at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. Osteological studies such as these provide insights into the diet, health, appearance, activities, and origins of early peoples in North America. The adult male is estimated to have been near 40 years old at the time of his death, based on measurements, growth and aging indicators. In stature, he would have measured between 5 feet 3 inches and 5 feet 4 inches (162 to 166 cm). Of particular interest is evidence indicating he had been engaged in strenuous, repititve activities involving use of his forearms, resulting in well-developed muscle attachments, and robust development of his right thumb and forefinger, indicating repetitive gripping motion. Jodry and Owsley suggest these unusual attributes may relate to shamanic drumming and repetitive healing tasks, such as body painting. There were few signs of disease or medical disorders in the male skeleton. The man had suffered an infection of the left maxillary sinus and a fracture on the left foot, which had healed completely. Other foot bones showed abnormal growth, possibly due to mechanical stress or infection. Transverse, or Harris, lines on the femur and tibia (lower limb bones), may indicate he had experienced disease or nutritional deficiences while young. The individual had lost permanent teeth (a maxillary incisor and portions of the mandibular molars) before death, causing him to have only two or three functional chewing surfaces. Those teeth remaining were heavily worn, likely related to a coarse hunter-gatherer diet and, as Owsley has noted, possible use of teeth as tools. The bones of the juvenile were much thinner and less well preserved than those of the adult. Age of this indivdual was estimated at 10 to 12 years old, based chiefly on dental eruption and dental calcification. All of the permanent teeth had emerged, although one deciduous, or baby, tooth (left maxillary secondary molar) was still present. The deciduous molar showed heavy attrition, its chewing surface worn into a concave depression and down to secondary dentine. There were only light to moderate signs of wear on the other teeth. Only a trace of shoveling was observed in the central maxillary incisors, and none on the lower incisors. Both Young and Owsley noted small pits on the lingual surfaces of the juvenile's upper first molar. Identified as Caribelli's trait, or cusp, this feature is not common in Native American populations. Caribelli's trait has a higher incidence among Caucasoid populations than Mongoloid, based on a scorings by physical anthropologist Christy Turner. The sex of individuals this young is often difficult to determine, especially given deterioration of post cranial elements typically used to make this assessment. Although Young tentatively identified the individual as male, there are aspects of the dentition suggesting the juvenile was female. The presence of a bone sewing needle, traditionally associated with females, also suggests this identification. The causes of death of the Horn Shelter individuals were not revealed by osteological analyses and, for the present time, remain a mystery. Other than signs of a minor sinus infection in both the man and child, there were no indications of serious medical conditions or signs of trauma. Both Redder and Dee Ann Story have suggested that the apparent simultaneous death of both persons is noteworthy and would seem to lead to certain interpretations. Either the two were both struck down by an unknown calamity, or the youth was sacrificed following the death of the adult male. Given the richness of the grave offerings, the man obviously held high status in his group. And, if the young child were female, she may have been his wife. As Story noted, the loss felt by the group, or perhaps the extent of the man's power, is evident in the careful burial at Horn Shelter. Face from the PastBecause of the rarity of Paleoindian skeletal remains, little is known about the physical characteristics of earliest peoples. A number of features, however, suggest that Horn Shelter man derives from different ancestry from modern Native Americans. His long, narrow skull and relatively short face more closely resemble the Ainu of Japan, who are known to carry European traits, rather than the more round skulls, broad faces, and pronounced features represented in some modern Native American populations. Certain evidence in the teeth of the Horn Shelter juvenile also tends to set her apart from Native Americans, including shallow depth of incisor shoveling and the presence of a small cusp of Caribelli. Interestingly, physical anthropologist Matthew Taylor has found a lower incidence of shoveling in prehistoric skeletal remains from the Texas Gulf Coast compared to more inland sites in the state. Caribelli's trait is common among prehistoric coastal populations, based on Christy Turner's scoring. Additional analyses of early human skeletal remains in the U.S. are detailed in Arch Lake Woman, Physical Anthropology and Geoarchaeology (2010 Texas A &M University Press) by Owsley, Margaret Jodry, and others. In addition to reporting findings from the Arch Lake site in New Mexico, the book also synthesizes and compares skeletal and cultural materials from several other early burial sites, including Horn Shelter. In his analysis, Owsley found dental traits in common between the Horn Shelter No. 2 juvenile and Arch Lake Woman in New Mexico. In certain aspects of cranial morphology, the Arch Lake woman was most similar to the Horn Shelter No. 2 male as well as Gordon Creek woman from a site in northern Colorado. These traits, he notes, are not representative of recent Native Americans. DNA analysis of bone from the Horn Shelter remains currently is underway. Results of these studies may provide further clues on the ancestry of these ancient people. Today, a bronze bust of the Horn Shelter man stands at the entrance to the Bosque Museum in Clifton, enabling visitors to gaze at a likeness of this face from the ancient past. Sculptor Amanda Danning performed this reconstruction based on a cast of the reassembled skull of the Horn Shelter adult made by physical anthropologist James Chatters. Working under the guidance of Owsley and others, Danning produced an approximation of facial features of the man, one of the earliest known inhabitants of North America. In addition to the sculpture, the museum holds an interpretive display of the burial scene and excavations at Horn Shelter. |

|