In addition to the human remains and funerary objects, clues regarding the identity and lifeways of the Horn Shelter people may be provided by the stone tools and weaponry, animal bone, and hearths found in the stratum (5G) associated with their burials. This dark gray midden deposit clearly reflects a great deal of activity by the groups or groups of people using the shelter: fires for cooking and warming were laid, tools and other gear fabricated and maintained, and a diverse variety of foods consumed.

Among the many stone tools were projectile points, bifaces, drills, gravers, unifaces, quartzite choppers, burins, utilized flakes, hammerstones, debitage, and red ocher. Animal bone, some of it worked, crushed, and/or burned, included remains of small mammals (rabbits, voles, rodents), birds, frogs, turtles, snakes, fish, and freshwater mussels. Deer and a few bison bones also were recovered. Except for a few charred walnut shell fragments found with the burial, there was no evidence of plant use, although a quartzite chopper tool may be an indication of processing. Like their predecessors at Horn Shelter, Late Paleoindian campers built their fires directly on the ground, leaving an imprint of ashy burned or stained soil. Rockless features such as these have been found at other early sites in Texas.

Stone dart points—Brazos Fishtail and Wilson—were found in both Sub-Strata 5F and 5G. Additional specimens of these types were recovered from Stratum 7, a location beyond the shelter's drip line which may be equivalent to Stratum 5 in the shelter interior. The possible correlation of Stratum 7 and its contents with the interior cave deposits should be of interest to future researchers.

Significance of Brazos Fishtail

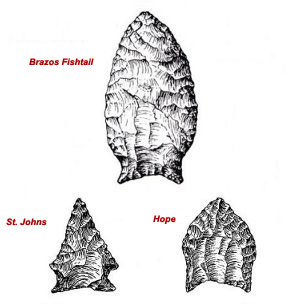

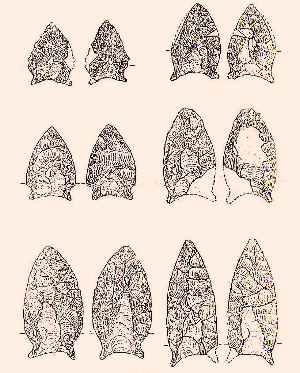

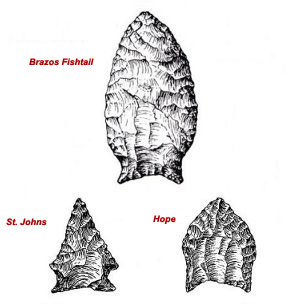

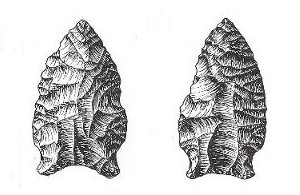

The Brazos Fishtail point, proposed as a separate type by Frank Watt in 1978 based on the Horn Shelter specimens, has been observed to resemble a variety of the San Patrice point found in eastern Texas and much of Louisiana. This southeasterly region is considered to be the “San Patrice heartland,” although the type also has been found in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Two “classic” San Patrice variants have been proposed: the notched St. Johns variety and the more lanceolate-based Hope. Both have been found at the Wolfshead site in San Augustine County, Texas, and at the John Pearce site in Caddo Parish, Louisiana. Other named San Patrice varieties from the Wolfshead site and sites at Ft. Polk, Louisiana are not as widely recognized as St. Johns and Hope.

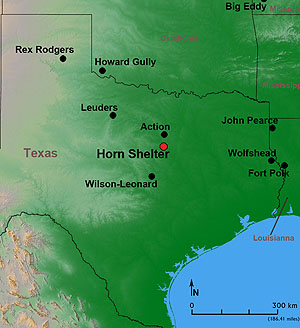

It is the St. Johns variety of the “classic” San Patrice point that the Brazos point seems to resemble, closely enough that the Brazos point is thought to reflect the westward movement of San Patrice peoples out of their home territory in the eastern Woodlands. A single St. Johns point was found upriver from the Horn Shelter at the Acton site in Hood County. Fragments possibly representing St. Johns points also were recovered from the Wilson-Leonard site in Williamson County.

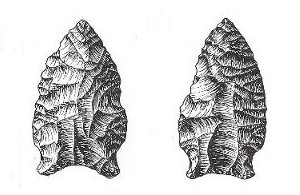

The Brazos point also resembles several specimens found at the Rex Rodgers site, well to the northwest of Horn Shelter. This Plains site is located near Tule Creek, a tributary of the Red River emerging from the Caprock Escarpment of the Llano Estacado in Briscoe County, Texas. Three points recovered from the site were observed to be within the San Patrice range of variation, and, within that range, to most resemble the St. Johns variety. However, authors of the Rex Rodgers report suggested that the points in question not be associated with any then-existing type and be characterized instead as “Rodgers Side-hollowed” points. Redder has noted that fluting on Brazos Fishtail compares favorably with the side-hollowed points from the Rex Rodgers site, although the ears of the Brazos Fishtail are finer and more delicate.

Another specimen resembling the Rodgers Side-hollowed points has been recovered at the Leuders site (41SF20) near the Clear Fork of the Brazos in Shackelford County, Texas, an intermediate location between Horn Shelter and the Rex Rodgers site. Archeologist Thomas Hester notes resemblance of this point to the large early stage Brazos Fishtail from Horn Shelter, particularly in its length and relatively unresharpened state. The point was made on fine-grained glossy gray chert, with pink coloration suggestive of heat treating. Long thin flutes were removed from both faces.

Other points classified as San Patrice-like, resembling Side-hollowed or Brazos variants, have been found in Texas Archeological Research Laboratory collections from other northwestern Texas counties, including Runnels and Callahan. A particularly intriguing specimen, collected by E. B. Sayles in the 1930s, was made on a fine-grained material with vertical basal thinning flake scars emmanating from the base, hinging on an embedded fossilized plant on one face. An additional western San Patrice-like point was reported at the Steadman site in Fisher County, Texas. Further to the southwest, a dart form with V-shaped basal concavity and concave haft, resembling some Hope or Side-hollowed forms, was recovered at Kincaid Rock Shelter in Uvalde County at the southern edge of the Edwards Plateau.

Perhaps the westernmost site with San Patrice points is the Hardwick site in New Mexico, just east of the Clovis site and 1 km north of Blackwater Draw. As reported by Stance Hurst and others, four San Patrice points of the St. John variety were recovered from a blowout area within an upland dune deposit. This locale, along with others previously noted, demonstrates connections between San Patrice and Plains cultures and the possibility that San Patrice was a Plains adaptation during the Late Pleistocene.

Wilson and Possible Connections

Stratum 5 of Horn Shelter also yielded a complete, although broken, Wilson point, one fragment in Sub-Stratum 5F and the other in 5G. Wilson points, so named by TxDot archeologist Frank Weir for the Wilson component of the Wilson-Leonard site and associated with the Late Paleoindian burial there, have been described by archeologist Britt Bousman as representing one of the “earliest stemmed projectile point occurrences in North America.” These large, relatively thick points have expanding stems typically with ground lateral and basal edges. The Horn Shelter specimens may suggest a temporal or cultural relationship between the two burials.

Four San Patrice basal fragments also were recovered from Late Paleoindian contexts at the Wilson-Leonard site, although these appear to post-date that burial and the Wilson component containing Wilson points. Nonetheless, the recovery of San Patrice-like Brazos points and Wilson point fragments from the same stratum of Horn Shelter suggests the possibility of a temporal overlap of two technologies and/or two related population groups. Recent analysis of Paleoindian material recovered from other sites may be relevant to that question.

The Big Eddy site, reported by Neal Lopinot, Jack Ray, and others, is located in western Missouri on the lower Sac River valley, along the west flank of the Ozarks in an ecotonal setting at the juncture of Plains and Eastern Woodlands. Excavations at the site recovered 13 San Patrice points within a rich Late Paleoindian deposit dating to ca. 10,500 to 9,800 radiocarbon years B.P. Two of the San Patrice points were classified as Hope variety, and the others as St. Johns. The apparent contemporaneity of the two varieties led the authors to suggest that the different styles represent co-occurring, rather than sequential, variations in technology.

This suggestion appears to have at least indirect support in findings reported by Thomas Jennings, who has concluded that San Patrice groups used both point variants concurrently. Using measurements on haft portions of 150 San Patrice points (representing both varieties and sites in Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas, including Horn Shelter specimens), Jennings conducted cluster analyses to determine frequency of occurrence of the two varieties and the degree of variation between them. He found that the points did not grade from the more lanceolate Hope form to the notched St. Johns form, but, rather, that the two varieties formed discrete clusters that represent “an abrupt technological shift.”

The Big Eddy site also has yielded evidence of a potential intersection of groups using San Patrice and Wilson, or Kirk Corner Notched, points, as well as Dalton points. Four corner-notched points/knives, three of which were identified as Wilson, were recovered from Late Paleoindian contexts at the site. Two apparently were made from non-local stone. With no other previously identified occurrence of Wilson points in southwestern Missouri, and San Patrice points relatively infrequent there, the Big Eddy investigators posit “forays of relatively short duration” into the area by the non-local groups represented by the San Patrice and Wilson points.

While at Big Eddy, some San Patrice toolmakers apparently shared a large knapping area with makers of Dalton points, the predominant type found at the site. From the debris they left behind, including bifaces, preforms, and waste flakes, archeologists have reconstructed point-making sequences for both San Patrice and Dalton types. Of interest, all but one of the 17 Dalton points recovered from Late Paleoindian contexts at Big Eddy were made of local stone. As characterized by Lopinot and Ray, the Big Eddy site appears to have been a gathering spot and "home away from home" for San Patrice groups during Late Paleoindian times.

Jennings similarly finds support for the likelihood of wide-ranging movement by San Patrice people, whether for subsistence or trade. Source analysis of the portion of his San Patrice point sample recovered in Oklahoma found that seven specimens were made from Edwards chert. Three of these were recovered in Marshall County, Oklahoma, which borders the Red River in the vicinity of Lake Texoma. Another specimen was from Jackson County, which borders the Red River near the Texas panhandle. The other three were from Caddo and Washita counties, both in western Oklahoma and north-northeast of Jackson County. These last three counties—Caddo, Jackson, and Washita—are all within 50 miles of each other. Jennings measured the distance from these counties to an Edwards chert outcropping at 240-285 miles. Distance from Marshall County was 330 miles.

Two additional specimens made of Edwards chert and resembling Rogers Side-hollowed and Brazos Fishtail were found at the Howard Gully site in Greer County, Oklahoma, in association with a 10,214 year-old bison kill. As archeologists Stance Hurst and others observe, the new data from Howard Gully suggest the manufacture of these "elusive" shallow side-notched points on the Plains occurred early, following Folsom. Metric comparisons indicate a relationship with San Patrice.

These varied reports and studies do not necessarily demonstrate that the makers of Brazos/San Patrice at Horn Shelter traveled widely or had extensive intergroup connections along or across the Woodlands-Plains border. They do suggest that contacts may have been likely, that any such connections may have occurred at a time when their hunting technology was changing rapidly, and, if so, that those two phenomena might be related.

Distinctions without a Difference?

The distinctions among Brazos Fishtail and San Patrice-like point varieties, as observed by those who have examined the specimens, have been noted at some length in this section, although it is not clear, as yet, whether these distinctions are meaningful. Similarities between variants of San Patrice and certain types within the Dalton Cluster in the southeastern United States, including Greenbrier and Hardaway Side Notched, have been observed. Based on basal fluting and outline of early stage points, some have suggested that both San Patrice and Dalton evolved from earlier fluted point types. This possible common ancestry is important, as may be the variant offspring and their geographical distribution.

Many archeologists, however, have advocated lumping Brazos, St. Johns, Hope, and other variants within the larger clasification of San Patrice, arguing that they represent a continuum of variation. Further studies on lithic materials from Horn Shelter and other sites, including raw material sourcing and technological analysis, may be useful in determining possible significance of these style distinctions. Whether they reflect cultural expressions of local groups, interactions with others, or differences in use or hafting technologies, may be further revealed.

Wilson points also have relevance in this discussion. Corner-notched points including Wilson and possible Wilson were recovered below, within, and above the layers holding the burial deposits at Horn Shelter. Based on use-wear analysis and co-occurrence of corner-notched Wilson with San Patrice at Big Eddy, archeologists Lopinot and Ray have suggested that Wilson may have been used as a knife by San Patrice peoples.

The unfluted lanceolate points, adzes, and perforators from the overlying deposits (Stratum 8) at Horn Shelter are of importance as well. Originally classified as Plainview, the lanceolate points strongly resemble southeastern Dalton variants; some display characteristic edge resharpening, beveling, and blade serration, or Meserving. Others in the lanceolate group bear further examination alongside types St. Mary's Hall and Golondrina-Barber. In general, the points are morphologically distinct from Plainview and are related to Late Paleoindian, rather than earlier, peoples. Similar points have been found at Wilson-Leonard and Big Eddy, as well as the St. Mary's Hall site in San Antonio.

The Horn Shelter Legacy

Evidence from Horn Shelter provides remarkable new insights but raises compelling questions, perhaps most particularly:

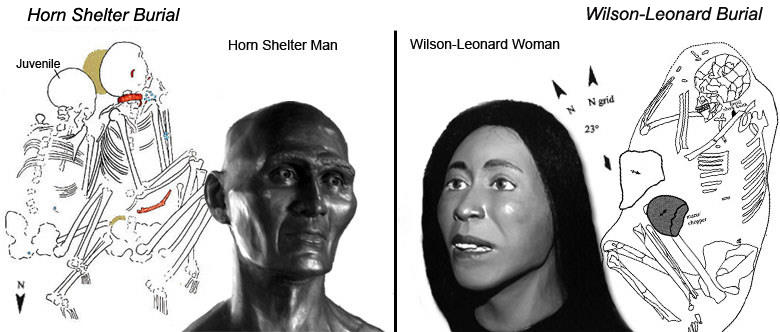

Who was Horn Shelter Man and who were his people? A number of features observed during osteological analysis of the human remains suggest that the two individuals derive from ancestry different from modern Native Americans. DNA analyses, currently underway, may offer additional insights and may indicate whether the man and young girl were related.

What was the extent of their "territory" for procuring natural resources, or trading with others? Several types of technical analyses may help identify sources of the raw materials used for tools. Such information helps us conceptualize the mobility patterns of the Horn Shelter people and their possible contacts or trade with groups in other areas. Redder has noted, based on visual inspection, the use of non-local materials such as Alibates flint (or dolomite) and novaculite among early Paleoundian tools, and an increasing use of local river gravels over time. The use of marine shell for ornaments placed in the Late Paleoindian burial clearly indicates connections to the Gulf Coast, via trade or travel.

Does the Horn Shelter grave represent the makers of Brazos /San Patrice, Wilson, or ? Both Brazos Fishtail and Wilson points were uncovered in the stratum from which the burials originated. At sites such as Big Eddy in Missouri, both San Patrice, Dalton, and possible corner-notched Wilson knives appear to have been used concurrently. With comparison of Late Paleoindian toolmaking technologies and subsistence patterns from the Horn Shelter and others of the time, including the nearby Wilson-Leonard burial site, the relationship of these point traditions—and the peoples who made them—may be better understood.

Other items, such as the eyed bone needle laid with the juvenile at Horn Shelter and the antler shaft straightener placed with the male, may hold technological clues and connections to ancient traditions. Similar eyed needles were found in Sub-Stratum 5D at Horn Shelter., as well as at the Lindenmeier Folsom site in Colorado and the ca. 10,500 years B.P. Buhl burial site in Idaho. Both types of tools have been found in Late Paleolithic sites in Europe.

At Horn Shelter, the unique double burial and grave offerings, along with the associated tools and food remains from the campsite, provide an unparalleled glimpse of an important, but little understood and much-debated period of North American prehistory. Because of the site’s careful excavation and documentation, future researchers will be able to apply new technologies to further analyze this outstanding and important set of remains.

|

Examples of the numerous and diverse unifacial tools from Horn Shelter Sub-Stratum 5G. A diverse assortment of other campsite remains were found in this dark midden layer including other tools, weapons, and animal bone. Photo by Albert Redder.  |

Brazos Fishtail from Horn Shelter and classic San Patrice point variants, St. Johns and Hope. Images adapted from Johnson 1989 (top), and Turner and Hester 1993. Enlarge for more detail.  |

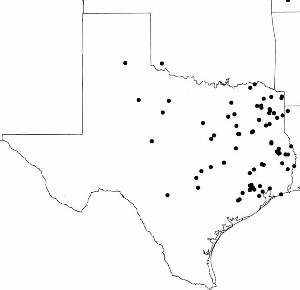

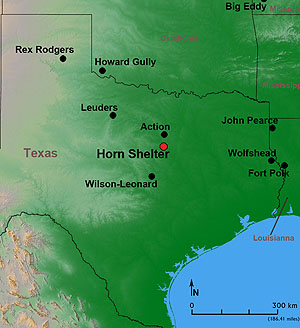

Locations of selected sites discussed in text, including those on western margin of San Patrice "heartland" in east Texas and northwestern Lousisiana. Map by Heather Smith, adapted from Jennings 2008.  |

Side-hollowed points from the Rex Rodgers site, drawn by Richard McReynolds from Panhandle-Plains Museum collection. (Inset of image from Turner et al. 2011, courtesy of the authors.)  |

Unusual fluted points from central northwest Texas counties. At left, fluted point from Shackleford County with similarities to Rodgers Side-hollowed variant. Photo courtesy of Thomas R. Hester. At right, point with vertical thinning of base interrupted by embedded plant fossil, Callahan County. TARL Sayles Collection; photo by Laura Nightengale.  |

Examples of Wilson points including refit specimen from Horn Shelter, top left, photo by Susan Dial, and examples from Wilson-Leonard site, TARL Archives. Enlarge to view additional specimens.  |

Examples of points identified as San Patrice from Big Eddy site, Missouri, including St. Johns and Hope varieties. Based on their position in a Late Paleoindian deposit, these two variants appear to have been used contemporaneously. Photo courtesy Center for Archaeological Research, Missouri State University. Enlarge to see additional specimens.  |

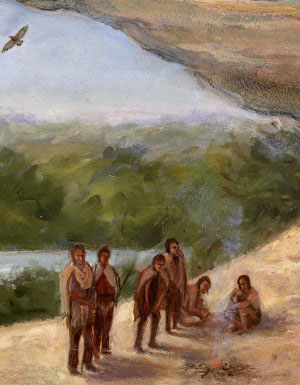

Brazos Fishtail, or San Patrice-like, points at Horn Shelter, as envisioned by artist Frank Weir. Inset from painting of Horn Shelter Burial.  |

| The Brazos point may reflect the westward movement of San Patrice peoples out of their home territory in the eastern Woodlands and onto the Plains. |

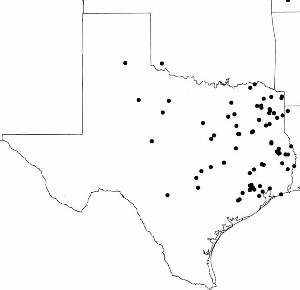

Distribution of sites with San Patrice and San Patrice-like variants in Texas, based on TARL and other collections (adapted from Figure 2.46h from Bousman and Kerr 2004).  |

|