| Fishhook Nomenclature

Hook Stock: Any bone fragment on which a fishhook is to be made. However unless a little preliminary work was begun, it is not possible to say that a bone of satisfactory dimensions was intended to be used as raw material for a hook.

Proximal Stock Remnant: That part of the stock likely used as a handle while cutting the hook to shape. It becomes a remnant after the hook is completed and has been removed.

Distal Stock Remnant or Basal Tab: That part of the stock that is removed from the base of the hook, in preparation for rounding the hook base and shaping the point. This basal tab may not always be present since they are rare in this complex. Both the proximal stock remnant and the basal tab may be used for another hook if they are large enough.

Fishhook – the finished artifact: A part of the hook is the shank, that long portion to which the fishing line is attached. This is the proximal end. It may be straight, flared, or knobbed and with or without line grooves encircling it. The base is that rounded part between the lower shank and the point. The point is that part by which the fish is impaled.

|

Close-up view of completed hooks. Photo courtesy of Baylor University, Mayborn Museum Complex with permission of Albert J. Redder.  |

Examples of small flake tools for hook-making. Photo by Susan Dial.  |

|

Among the thousands of animal bone fragments and chipped-stone flakes found in the Archaic zones at Horn Shelter were certain distinctive materials that caught the eye of investigator Albert Redder. After weeks of sorting bone and debitage collections followed by careful microscopic study, Redder began to recognize the products and byproducts of a bone fishhook manufacturing industry, including the tiny chert flakes used as fabricating tools.

With these materials, the avocational archeologist has painstakingly traced the likely steps of Archaic craftsman, from the selection and first shaping of raw material to completion of finished fishhooks. Redder's explanation of this technology, below, is drawn largely from his 1985 article first published in the Central Texas Archeologist.

From Deer Bone to Fishhook

Fishhooks at Horn Shelter No. 2 were made almost exclusively from fragments of the leg bones of a deer.

The bone fragments for hook stocks were obtained by breaking the leg bones; whether this was to secure marrow or only to make a hook has not been determined.

After a suitable stock had been chosen, a hole was scraped through the bone from the outside. This hole was then enlarged until the inside dimensions necessary for a hook were obtained. At this point, the basal tab was likely removed. This was accomplished by cutting a groove across the stock at the base of the hook and breaking off the tab. Work continued by rounding up the base (some hooks show evidence of abrasions in shaping the base; others do not) and generally shaping up the hook, forming the point and freeing it from the stock. At this time, encircling line grooves were probably cut if they were desired. One broken hook and stock shows the line grooves cut before the hook was freed from its stock.

At this point the hook was virtually complete. However, it was still attached to the stock. It was removed by cutting two grooves on each side of the bone where the end of the shank was to be and breaking the hook free. The workman then held in one hand a completed hook, and in the other a proximal stock remnant. This remnant may have been discarded or used to make another hook if it was large enough. Three proximal stock fragments and one basal stock show evidence of having been used to make more hooks.

A total of 33 specimens of fishhook material was recovered from Horn Shelter No. 2, south unit. Most are from the midden, Stratum 10, although several are from other Archaic strata. Nine specimens represent hooks broken and incomplete. Twenty-four specimens represent fragments remaining after the hook has been completed. Two charcoal samples from Stratum 10 were submitted for radiocarbon assay. The first, associated with bone hooks as well as Pedernales dart points, yielded a date of 3470+/-160 B.P. (TX-1720). The second, associated with Marcos points, was dated to 2330+/-60 (TX-1999).

Although fishhook material has been found throughout the area, it is not common in any one site. In the Lake Whitney Reservoir, hooks and stock have been found at the Kyle site, the Pictograph Shelter, Buzzard Shelter, Sheep Shelter, and Little Buzzard Shelter. From nearby areas other hooks have been found. One hook was from a shelter on a small tributary on the Leon River near Oglesby, Texas; one hook was from a shelter on a small tributary of the North Bosque River near Crawford, Texas; one hook was from a shelter on Stampede Creek near Lake Belton; and another hook was from a shelter on Hog Creek near Crawford, Texas. From Horn Shelter 1 a possible hook, broken, was made from a mussel shell, and three hooks were made from the leg or wing bone of a large bird. Others may have been found in other sites.

Hook-making Tools

In the process of excavating the Archaic midden at Horn Shelter and the finding of bone fishhook materials, the question arose, what kind of tool was used to make these hooks? It was obvious that snubnose scrapers or other large scrapers could not have been used to shape the small inside curve of these hooks. In addition, practically no large scrapers were found. After much discussion with Frank Watt and analysis of used flakes, a pattern began to emerge.

Certain flakes that were triangular in form, with a used edge generally along one side, had on this edge near the small end a small notch. This notch varied from 1/8 inch across to slightly larger and from shallow to as deep as the width. Theoretically, these tools would work admirably, rounding out the inside portion of the hook as well as shaping up the outside and freeing the point. It has not been satisfactorily decided what tool was used to start the process by cutting the first hole through a bone, but a short stout graver would have worked well.

At least eighteen utilized flakes from the midden appear to have been “fishhook-making tools.” Similar notched flakes are not found in the Paleoindian assemblages. Utilized flake material from other sites having a fishhook component needs to be analyzed to see if this type of hook-making tool is present, and the assemblage checked against sites not having fishhooks.

Based on the amount of bone hook fragments and the apparent flake tools used for their manufacture at Horn Shelter, one thing is apparent – fishing was an important industry at this time and place. Large quantites of fish bones, including gar, freshwater drum, and channel catfish also were recovered in the Archaic levels, providing us an indication of the variety of fish sought by the Archaic anglers. Although some may may have been caught in nets, we can surmise that the fishermen caught a number of these using their intricate bone tackle.

|

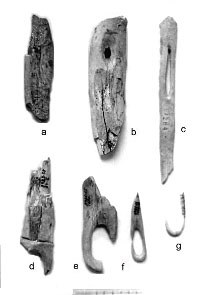

Fishhook material. A, Hook stock with partially scraped out area; B, Hook stock with hole scraped through; C, Hook stock of bird bone with hole scraped through; D, Hook stock cut for removing basal tab but hook broken instead; E, Hook completed with proximal stock remaining – point was broken later but not in excavation; F, Completed hook with proximal stock remaining; G, Finished hook, straight shank with line groove. Specimens G, D, E, F are from Horn number 2; the remainder are from Horn number 1. Photo by Al Redder.  |

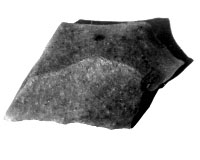

Example of small chert flake used as tool to make prehistoric fishhooks. Photo by Al Redder.  |

Fishhook material. Proximal hook stock remnants, rows 1 and 2. Row 3, left, basal tab; center, basal tab on which another hook was made; right, proximal stock remnant on which two hooks were made. The opposite corresponding point is missing. Row 4, broken fishhooks, with straight and flared shanks with line grooves cut at neck; far right, stock remnant on which line grooves were cut prior to removal of hook. Apparently the hook broke instead. The shank is not yet grooved for breakage.

Photo by Al Redder.  |

Examples of small flake tools for hook-making. Photo by Susan Dial.  |

|