Investigations

|

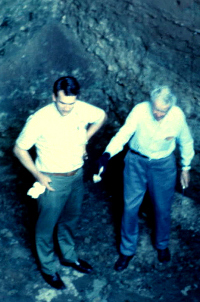

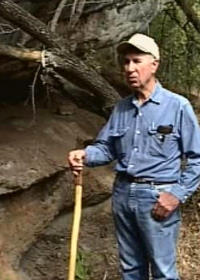

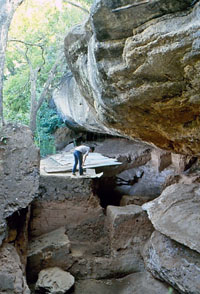

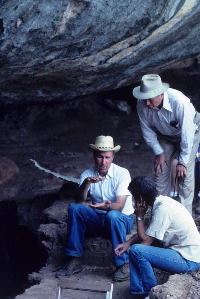

When Al Redder and Frank Watt began investigations in the south end of Horn Shelter No. 2 in 1966, they had no idea their work would extend over several decades, nor that they would uncover one of the oldest and most significant graves in North America. Their previous excavation at Horn Shelter No. 1 several hundred yards downstream had uncovered an abundance of cultural materials in well-stratified deposits. When they began work at the second Horn site, much of the large shelter was filled almost to the ceiling with sediments and occupational debris. Undaunted, the men began their testing of Horn Shelter No. 2 to gauge the depth of cultural deposits and determine whether Paleoindian materials were present. The two avocational archeologists were a familiar and seasoned team, having discovered and excavated numerous sites in the region, often with other members of the Central Texas Archeological Society of Waco. The legendary Watt, one of the founders of that group, had served as a mentor to the younger man, guiding him in archeological field techniques and documentation methods. On his own, Redder was an avid researcher who studied archeological journals and reports and made replicas of artifacts to help interpret the evidence they were uncovering. At Horn Shelter No. 2, Redder and Watt developed a routine of working one or two days on weekends at the site. Their efforts, unfortunately, drew the attention of artifact hunters and fishermen who often trespassed on private land to dig through the Brazos River shelters. Avocational archeologist Robert Forrester previously had dealt with relic collectors when he first attempted to test Horn Shelter No. 2. As he later wrote, he “quit in disgust” because of their destructive activities. After he left the site each week, collectors would dig into Forrester’s carefully excavated units and smoothly profiled walls, searching for artifacts. In time, however, Forrester returned to assist Redder and Watt in the excavation of Horn Shelter No. 2 and to help guard the shelter while its most important cultural remains were documented and removed for safekeeping. He ultimately excavated much of the north end of the shelter, and published his findings in a 1985 Central Texas Archeologist article and a 1996 Baylor University publication. (Findings from the north end are not covered in this exhibit.) Excavations in the South EndAs shown in the plan map below, Horn Shelter No. 2 is naturally divided into two sections by a rock ledge, or “balcony,” which protrudes into the shelter roughly at its midpoint. The larger, south end of the shelter extends some 45 feet north-south, with an interior area extending roughly 30 feet to the back of the shelter. The floor slopes downward to the front of the shelter, and slightly to the north as well. The floor and back of the shelter are typically muddy and slick due to a seep spring emanating from the back wall. These conditions, along with carbonate layers as "hard as concrete," made working conditions challenging for the men. |

|

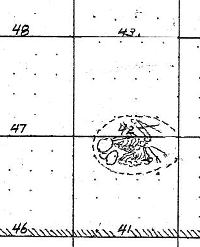

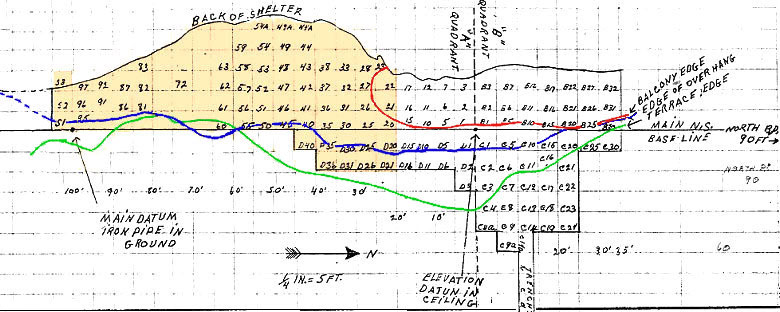

Plan map of excavation units at Horn Shelter. The south end (highlighted) is naturally separated from the north end by a rock ledge, or "balcony" (outlined in red). The south end is the focus of this exhibit. Map by Albert Redder.

|

|

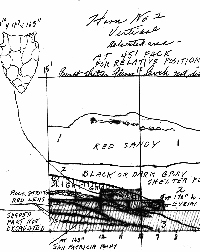

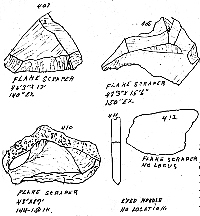

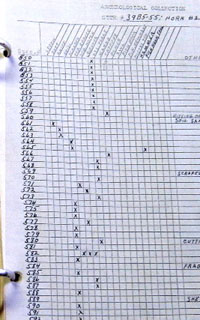

To begin their investigations, Redder and Watt excavated a 5-foot trench in roughly the middle of the south half of the shelter to assess the depth and character of the deposits. Some 5 to 6 feet of fill already had been removed from this end of the shelter. When, how or why the removal took place is not known, but it may have been due to a combination of natural and human forces. Flood waters removed some of the sediments, clearing the way for turn-of-the-century campers who apparently enlarged the space further for use as a dwelling. These squatters were followed by relic collectors who dug out a large area of the south half of the shelter, destroying up to 7 vertical feet of Archaic and Late Prehistoric deposits. After shoveling out and screening most of the disturbed deposits, Redder and Watt established a grid system of 5-foot squares with base line running north-south, roughly paralleling the long axis of the shelter at the outer edge of the overhang. (As was common at the time, the English system, rather than metric, was used for measurements.) An elevation datum was established at the highest point of undisturbed fill, and a steel pin from which to take measurements was set in the ceiling at that point. This datum was 100 feet north of the permanent reference point, a steel pipe driven into the ground just beyond the south end of the shelter. A 6-inch layer of dirt was removed in order to establish a clean level floor for profiling. Although the first profile revealed a large area of disturbed soil, much of the fill appeared intact. Excavation continued in 12-inch levels but followed the natural and cultural stratigraphy; a profile was drawn at the bottom of each 12-inch level. Wall profiles also were drawn at each 5-foot north-south line and east-west line. The bedrock floor of the shelter was reached at 207 inches below the elevation datum. Although the excavators followed each stratum, or layer, separately, they also maintained square and depth data for documentation. The strata, for the most part, could be easily recognized, although deposits under the shelter’s dripline presented a more complex picture. Upland sediments had periodically washed over the top of the overhang and fragments of limestone broke off and fell into the mouth of the shelter. Flooding, too, had caused several anomalies, disturbing or in some cases removing portions of the layers. Redder and Watt used a pick and shovel to dig most of the deposits, but a hand trowel was used to excavate features and certain other areas which required particular care. In some strata, the excavators encountered hard cement-like lenses—fine-grained sediment which had hardened over time into concretions of varying thicknesses. These concreted layers were so hard the excavators had difficulty digging through them, and some required use of a large pick. As Redder notes, " Why these concreted spots occurred here and there is unclear, but likely it was dependent on the amount of moisture present at different times." Some of the chunks of cemented matrix had artifacts, such as dart points and tools, embedded within; these were brought back to the laboratory for removal. Excavated sediments were screened through ¼-inch wire mesh except for fill from features (such as fire hearths) which was bagged separately and carried out to be carefully sifted through fine-mesh window screen. Artifacts and features were recorded by square, depth, and stratum, and artifacts assigned a specimen number. All flint, bone, and mussel shells (except for shell fragments) were collected, as well as a large sample of snail shells. Additional samples of charcoal and shell were submitted to the University of Texas Radiocarbon Lab and other laboratories; from these, a suite of dates was obtained. Palynologist Vaughn Bryant took a column of sediment samples in hopes of extracting pollen for paleoenvironmental studies. However, preservation proved to be poor, due to the wet-dry cycle of the shelter. Discovering the GraveAfter working at the site on most weekends over a period of three years, Redder and Watt made their most significant discovery. On a blazing August day in 1970, Redder uncovered a rounded yellowish bone, clearly a human skull, in the heavy gray stratum deep within the shelter. Once the find was conclusively identified as a burial, the men carefully covered it over with dirt to hide and protect it from vandals. They were determined to wait until they had a full three-day weekend to attend to the critical discovery. Further excavations revealed the burial was much more complex than they had imagined. Nineteen large limestone slabs had been placed as a covering over the body. While carefully probing around the skull, the excavators discovered a second skull about 2 inches from the first. Although the heavy rocks and overlay of cave deposits had crushed many of the smaller bones, the skeletons were remarkably intact. Over the weekend, Redder, Watt, and Forrester worked relentlessly to remove the human remains and the accompanying artifacts. Because of fear of what relic collectors might do, they determined not to stop until the burial was completely removed. By Sunday at dusk, the skeletons were largely ready for transport. Only the two skulls remained in place. Hoping to shoot one more photograph in the darkened shelter, Redder lit a make-shift torch of newspaper, then captured the skulls in the fire's glow. As they carefully prepared the skulls for removal, the men made another remarkable discovery: under the skull of the male lay a cache of artifacts encased with three turtle shells. As Redder noted, the process of removal became more difficult: Near the end of the third day, the skulls had not been removed, and it was then the cache under the head was discovered. Not enough time remained to excavate this carefully, so the cemented matrix beneath the burials was cut through, and the skulls lifted out still in place to be cleaned in the lab. Thus the skulls could be separated from the cache (to which they adhered with calcium) without breakage and the cache could be positioned back in original position on its cemented pedestal. Looking back, Redder notes, "I wish I could have jacketed the burials completely [in plaster] and brought them back to the lab intact, so I could have screened all the dirt on window screen." Had he done so, however, the effort might have taken longer and resulted in serious loss to vandals or relic collectors. As it was, the exacavators managed to keep the find a secret from all but a few archeologists, who periodically consulted with the men. Watt continued his efforts at the shelter until a few years before his death in 1981. Redder, working mostly alone from that point forward, continued excavations for another decade, devoting more time to the site after retiring from General Tire and Rubber Company in Waco. During this time, Jannett Watts became a periodic helpful assistant. In 1985, Redder published a preliminary account of his findings in the Central Texas Archeologist, and a more detailed account of excavating the gravel in a 1988 CTA article with John Fox. Except for a small remnant of deposits, the south end of Horn Shelter No. 2 was completely excavated, resulting in the identification of 27 strata representing more than 12,000 years of human history. (These strata, and the key cultural materials and features found within each, are characterized in the following interactive section, Reading the Layers. Findings related to the skeletal remains are detailed further in a separate section, A Paleoindian Grave.) Laboratory WorkFor Redder, investigations of Horn Shelter No. 2 did not stop with the cessation of field work. For the last two decades, he has devoted much of his time to the materials recovered from the shelter: cleaning, cataloguing, classifying, drawing and photographing the artifacts as well as organizing loose-leaf binders full of field notes, feature forms, maps, artifact inventories, drawings, and photo logs. |

|

Vials of small animal bones, painstakingly recovered after washing sediment through nested screens, have been sorted by element and identified by Albert Redder. The thousands of tiny bones様izards, mice, fish, etc.耀hown here were from an enigmatic feature in Stratum 4. Photo by Albert Redder. |