Kincaid Shelter was mentioned

only briefly in E. H. Sellards' 1952 book, Early

Man in North America. The site is of interest,

he noted, "as one of the southernmost localities

at which typical Folsom points are known to occur." Sellards, who directed investigations at the site

in 1948, made no mention of the stone pavement.

The Clovis artifacts from the site had not yet

been recognized.

Click images to enlarge

|

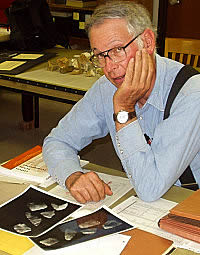

Paleoindian specialist Michael

Collins reviews photos of artifacts from the Late

Pleistocene Zone 4 deposits at Kincaid. His reanalysis

of these early artifacts and other data finally

answered the question, "Who built the stone pavement

at Kincaid?" Photo by Susan Dial.

|

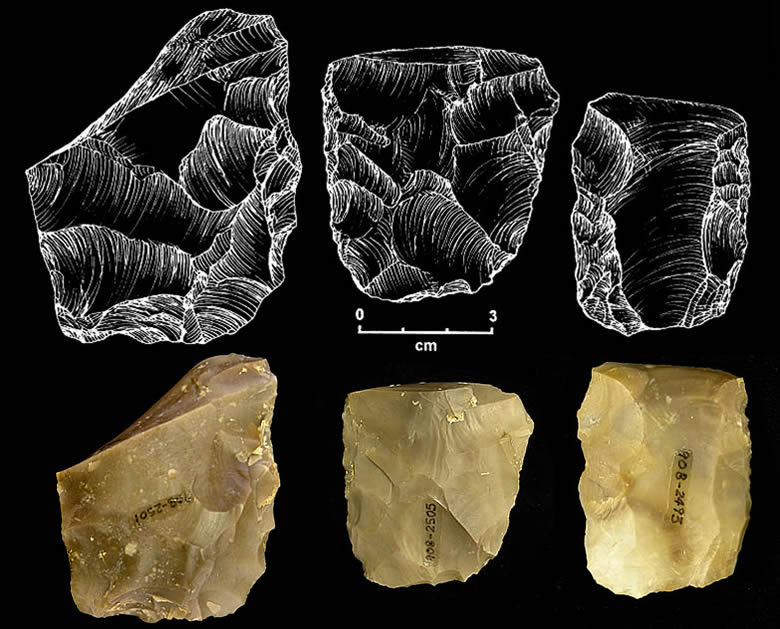

The re-joined Clovis biface,

or preform. Before they were recognized, the sections

had been separated in two different institutions

since the 1950s: the pointed distal section on

display at the Texas Memorial Museum, and the

base at TARL. The broad flake scars extending

nearly across the face of the biface are characteristic

of Clovis technology. The object was broken during

manufacturing, according to Collins, after the

first flute had been removed. Photo by Aaron Norment.

Click to enlarge and see drawing.

|

Artifacts from Zone 4. Photos

by Aaron Norment. Click to see full image.

|

|

Coming Full Circle

There are aspects of serendipity and no

small amount of irony in the Kincaid discoveries, beginning

with Gene Mear's find of a Folsom point in the backdirt

piles left by treasure hunters. Had it not been for

the destructive activity of the treasure seekers, Mear

would not have discovered the Paleoindian points, scientific

investigations might never have taken place, and the

ancient stone pavement at Kincaid Shelter might never

have been uncovered.

The serendipity was to continue and come

full circle in subsequent years.

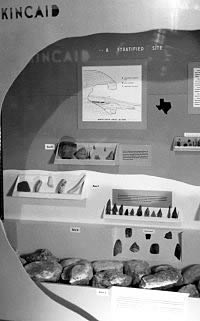

In the early 1950s, findings from Kincaid

Shelter were showcased in what became a longstanding

exhibit at the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin. Along

with a selection of artifacts, a section of the ancient

stone pavement was recreated and displayed. The text

for the exhibit explained that, while evidence of the

Folsom culture was found at the site, it was not known

what ancient civilization had constructed the

stone pavement—the thinking of the time perhaps

being that brutish hunter-gatherers would have had neither

the organizational skills nor the inclination to put

forth the effort required.

UT-Austin archeologist Michael Collins

recalls visiting the Kincaid exhibit as a young boy,

pressing his face against the glass display window,

and wondering about the ancient people who had created

the stone floor in the shelter. The question was to

nag him over the years as he went off to college and

began studying archeology and prehistoric cultures.

In 1988, armed with a Ph.D and some 20

years experience in the field, Collins obtained permission

to examine the Kincaid artifacts, still on display at

the museum. One specimen caught his attention—the

tip of a broken biface that had been recovered from

Zone 4. Looking at the flake scars on the fragment,

Collins recalls, "I knew that was Clovis technology."

At the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, where

the bulk of the Kincaid collection had been curated,

Collins examined the rest of the collection. There,

among a bag of triangular bifaces classified as "Kinney"

type specimens, Collins spotted a fragment with a fluted

base and unusual flaking pattern.

He held up the basal fragment next to

the photo of the tip from the museum display. The break

on the object in his hand was a mirror image of the

one in the museum display. After 40 years of being housed

in two different facilities, the two pieces were joined

together. It was, as Collins had suspected, a Clovis

preform, broken by an ancient knapper attempting to

make a spear point some 13,000 years ago.

The Case for Clovis

For Collins, the mystery of who had built

the stone floor at Kincaid had been answered. In subsequent

years, as he begun delving into early Paleoinidan tool-making

technology, Collins identified other Clovis artifacts

from the Kincaid collection—an expended conical

blade core, more fluted bifaces and preforms, and other

distinctive knapping debris.

Collins also interviewed longtime friend

and mentor Glen Evans, who had excavated the site in

1948, "picking his brain" for recollections

about other artifacts, such as long thin, Clovis blades—another

distinctive Clovis signature—which might not have

been collected at the time. (During the 1940s and 1950s,

it was not standard procedure to collect all lithic

materials found during archeological excavations.) Evans

was certain there had been no thin blades in Zone 4.

Gene Mear, who had retired after a successful

career in petroleum geology, later joined Collins in

examining the site records and re-inventorying the Kincaid

collection, measuring and recording attributes on the

chipped stone tools.

Having sifted through the collection and

the records for any other possible evidence pertaining

to Zone 4, Collins and his colleagues summed up the

newly identified Clovis lithic materials from Kincaid

in a short article in Current Research in

the Pleistocene:

From on and just above the pavement

were recovered flakes, a blade core, two bifaces broken

in early stages of reduction, a preform broken during

percussion thinning after successful removal of one

flute, and preparation of the platform for the second

flute, a basal fragment of a lanceolate obsidian point,

and three large retouched flakes. A reworked Clovis

point and several non-diagnostic pieces with adhering

travertine recovered from the looter's backdirt almost

certainly belong with the Zone 4 specimens. The chert-working

evidence suggests a Clovis habitation.

|

|

In this section:

|

The Kincaid Shelter exhibit

at the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin from the

1950s to 1990s, recreated a small section of the

stone pavement and posed the question, "What ancient

civilization built this?" For archeologist Mike

Collins, who visited the museum as a boy, the

question was to haunt him for decades. Photo courtesy

Texas Memorial Museum, University of Texas at

Austin.

|

Geologist Glen Evans examines

a thin blade from another Clovis site on a recent

visit with Mike Collins at TARL. No blades were

collected from the Kincaid site, and Evans, today

relying heavily on a sense of touch to compensate

for encroaching macular degeneration, is quite

certain there were none in the Zone 4 deposits.

A longtime friend and mentor of Collins, Evans

has talked about the site with his younger colleague

on numerous occasions and is anxious to bring

the site to the attention of the public. Photo

by Susan Dial.

|

Collins published his 1999

study on Clovis Blade Technology based on tools

from several sites, including Kincaid (University

Texas Press). |

Kincaid researchers were on

hand to give a talk about the shelter during a

nighttime meeting of the Texas Archological Society

field school in Utopia. Glen Evans is shown at

left, and Gene Mear, right. Archeologist Tom Hester,

shown center, directed the Utopia field school,

and commissioned a trace element study on the

Paleoindian obsidian artifact found at the Kincaid

site.

|

|

|

This series of Clovis bifacial preforms

illustrates knapping gone wrong at different stages, from

early stage reduction failures, left and center, to a first

fluting attempt, right, that severed the preform in half.

Drawings by Pam Headrick. Photos by Aaron Norment.

|

Gene Mear, left, re-inventoried

and measured many of the chipped stone tools from

Kincaid. Here he reviews a site map with Mike

Collins. Both researchers hope to fully analyze

and report their findings in the future. Photo

by Susan Dial.

|

Bone sampled in early dating

attempt. In 1954, samples of bone, charcoal, snail,

and and other materials from the site were submitted

for radiocarbon dating, a pioneering new technique

that Willard Libby was struggling to perfect at

that time. None of the results on the Kincaid

materials, however, proved satisfactory. This

bone sample, like the others, was wrapped in foil

as it was uncovered at the site as a protection

from contamination.

|

|

No recognizable Folsom-period debitage or

manufacturing failures were identified at Kincaid.

As opposed to evidence of habitation, the five

virtually unbroken Folsom points from the site

are more characteristic of a kill sites.

|

One of the five Folsom points

from Kincaid. Notably, all of the points are virtually

complete, although two, including this specimen,

have apparent impact fractures (note the damaged

tip section).

|

Clovis blade cores from several

sites. The small, expended Kincaid specimen (d),

lower right, is not easily recognizable as such,

and is dwarfed by the more classic examples (a-c)

from other sites. Drawing by Pam Headrick featured

in Clovis Blade Technology by Michael Collins

(1999, UT Press, Austin). Click to enlarge.

|

The stone pavement at Kincaid,

oldest known structural feature in North America.

Photo by Glen Evans. Click to enlarge.

|

American horse, Equus. A bone

from this extinct species was found on top of

the stone pavement, helping to establish the feature

as Late Pleistocene in age. Drawing by Hal Story.

|

The plastron, or bottom plate

of a turtle (Terapene carolinus), found in Zone

4. Although bones of megafauna, such as mammoth,

bison, and horse, were found in Zone 4, the identification

of smaller species, such as turtle and alligator,

supports new viewpoints about a broad-spectrum

Clovis diet. Turtle, in particular, has been found

in numerous Clovis sites. Photo by Susan Dial.

Click to enlarge.

|

|

Dating the Deposit

The handful of artifacts from Zone 4 and

the reworked projectile point from disturbed fill was

not sufficient evidence at the time to totally convince

other archeologists that the deposit could be attributed

to Clovis peoples. But there was no other evidence,

such as a radiocarbon date for the deposit, to strengthen

the case.

Earlier attempts at dating Kincaid samples

had proved unsuccessful. In 1953, upon learning of the

pioneering new radiocarbon dating techniques being tested

by Willard Libby, Evans had begun a persistent letter-writing

campaign to include some of the Kincaid samples in the

study. Because some of the samples were from contexts

associated with diagnostic projectile points or Late

Pleistocene fauna—and thus placed in a relative

chronological framework—Libby finally accepted

several samples as good test cases for his new technique.

In each case, however, the results were unsatisfactory—either

far too young or too old based on the evidence at hand.

Several of the samples used were snail shells, bone,

and other materials which are now known to require special

calibrations and processing methods. (Over the ensuing

years, Libby improved his technique and was awarded

the 1960 Nobel prize for his work.)

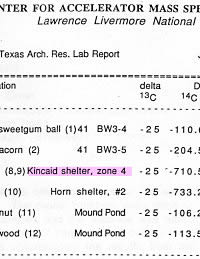

In 1990, Collins tried again, submitting

two painstakingly collected samples of charcoal to the

Lawrence Livermore Laboratory at the University of California-Berkeley

for accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dating. A major

advance over standard radiocarbon dating, this revolutionary

new technique can evaluate the age of even minute samples

of charcoal. The two Kincaid charcoal samples, Collins

recalls, looked like "flecks from a pepper shaker."

Using tweezers, he extracted the first speck from the

surface of a lump of travertine that had been collected

from Zone 4. The resulting radiocarbon age estimate

of that sample proved to be unsatisfactory, perhaps

contaminated during initial collection or storage.

To produce a second sample, Collins crushed

the travertine lump and removed a charcoal fleck from

the interior. This sample brought results—an AMS

radiocarbon age estimate of 9910 +/-250 years before

present, or, in calendar years, roughly 12,000 years

old. What this established, in effect, was an end date

for the accumulation of Zone 4 deposits.

Haunting Questions

Did Folsom people live in Kincaid Shelter?

Five Folsom points were recovered from

disturbed contexts at Kincaid, and these points are

interesting in several regards. They are all essentially

complete, except for minor impact fractures on three.

But it appears that they are the only evidence

of Folsom people at the site. According to Collins,

there is no other artifact—such as channel flakes,

distinctive fluted preforms, or fragments of Folsom

points— that can be attributed to a Folsom assemblage

from the site. No recognizable chipping debris or Folsom

manufacturing failures (broken tools) were identified.

As opposed to evidence of habitation, the five virtually

unbroken points are more characteristic of a kill sites.

Collins notes that since all five points

came from the backdirt of the large pit, they evidently

laid in close proximity near the back of the shelter

at one time. The points did not have any travertine

coating and, therefore, seem to post-date Zone 4. The

articulated leg bones of a single bison lay on the surface

of a travertine deposit at the contact between Zone

4 and Zone 5, adjacent to the largest pit.

A very intriguing and plausible explanation

of these circumstances has been proposed by Dr. Dee

Ann Story, who as a student dug at Kincaid in 1953.

In her hypothesis, Folsom hunters may have wounded a

bison with multiple darts. The bison apparently escaped

and perhaps sought refuge in the shelter. It died of

its wounds on the floor of the shelter (then the upper

surface of Zone 4) at a spot later penetrated by the

treasure-hunters. Their digging dislodged the majority

of the bison skeleton and all of the points, leaving

only the articulated limb bones found adjacent to the

pit at the contact between Zones 4 and 5.

Unfortunately, the nature of the Folsom

presence at Kincaid will remain a matter of speculation.

Because the deposit containing Folsom materials was

evidently almost totally disrupted by a treasure-hunters'

pit, it must not have covered a large area to begin

with.

What was the size and

lifestyle of the Clovis group?

Because of a variety of disturbances to

the deposits and because of incomplete recovery of artifacts

by investigators, our picture of the ancient groups

who stayed at Kincaid will remain blurred. Based on

the size of the stone pavement section uncovered during

controlled excavations— roughly 10 square meters—it

is clear that ancient builders expended substantial

effort in its making, But there is no way of knowing

what its original, full dimensions might have been.

Lacking that evidence, speculation about

group size is rather meaningless. However, the shelter

is large—roughly 35 by 32 feet, or 10 by 11 meters.

As Collins has noted, even though the known paved area

is comparatively small, it required considerable effort

to construct. These facts, he adds, suggest a group

of sufficient size to have required the entire floor

space of the shelter. And they would have intended to

stay sufficiently long to warrant the effort to build

the pavement.

Based on the artifact evidence, it seems

clear that the shelter was used as a habitation and

as a Clovis "workshop" for making chipped

stone tools. We can imagine a scene13,000 years ago

when a Clovis craftsman, perhaps wielding a heavy antler

baton, struck blades off a small chert core. Another

worker may have refreshed his hunting gear by pulling

a broken black-glass projectile point from a dart shaft

and replacing it with a new tip.

With the exception of the obsidian point,

the tool stone chosen, almost uniformly, was local Edwards

chert, based on appearance and on a cursory scan with

ultra violet light by Collins. The resharpened Clovis

point found at Kincaid is of interest in this regard.

As Collins notes in his study, Clovis Blade Technology

(1999, University of Texas Press), the fact that the

discarded point at Kincaid was made of the same local

material as the knapping debris indicates a return to

the same chert source within the use-life-span of the

points.

The Kincaid Legacy

With the analysis and identification of

the Clovis artifacts, Kincaid Shelter took its place

in a relatively small universe of early Paleoindian

sites. Several aspects distinguish it from others, while

other Kincaid evidence provides support for an ongoing

shift in our thinking about these early groups.

- The stone pavement is the oldest

reported construction in North America, some 13,000

years old. At other sites, such as Hell Gap and

Agate Basin, investigators have found the remains

of possible tent stakes made of bone or tusk, but

these sites are younger than Kincaid by 1,000 to 1,500

years. At the Vail site in Maine, there is an arrangement

of huge boulders, cobbles, and chipped stone tools

on a stream-side gravel bar. Although their arrangement

is circular, the boulders are too massive to have

been moved by humans. It is possible they were used

as supports for some sort of structure.

There is also a suspected Clovis-age structural feature—a

rectangular gravel pavement—that was uncovered

at the Gault site north of Austin, but findings from

this major Clovis occupation site are still being

analyzed by Collins, the lead investigator, and his

team.

According to Collins, Kincaid is the only site with

indisputable evidence of Clovis-period construction,

and "there is the bone of an extinct horse lying

right on top of the pavement." Further, because

the site was excavated by geologists employing stratigraphic

principles, there is very sound stratigraphic context

for the pavement. Their geologic observations on the

type and arrangement of the limestone cobbles used

for paving stones (Edwards vs. Anacacho formation)

established further that it was not created by natural

forces, such as spalling.

- Kincaid is one of the first sites

known with an unequivocal Clovis component overlain

by Folsom. These are rare—only three or four

sites are presently known, the most important of these

being the Blackwater Draw site in New Mexico.

- Kincaid was the first site to produce

a Clovis blade core from a Clovis component and with

other Clovis materials.

- The obsidian projectile point base

found in Zone 4 is one of the southernmost obsidian

Paleoindian artifacts from a known stratigraphic context.

This is one item from Zone 4 that cannot be attributed

confidently to a Clovis assemblage, according to Collins.

It is of a size, thickness, and general outline comparable

to Clovis, and it does have basal thinning flakes

on one face. As Dr. Thomas R. Hester noted in his

trace element study, most of the obsidian Paleoindian

points found in Texas and New Mexico are Clovis. Obsidian

is a black, volcanic glass of unusual flaking properties.

The beautiful stone could only have been acquired

through trade or a long journey.

- Animal bones found in the Clovis

deposits (Zone 4) hint at a broad-spectrum diet not

solely based on big game. Along with bones of

horse, camel, bison, and mammoth, investigators also

found turtle, racoon, and alligator.

At other Clovis sites such as Gault, turtle and small

mammals have been identified as well. Turtle, in particular,

is gaining attention as the most common type of reptile

found in early sites in North America. These findings

are challenging the long-held notion of Clovis people

as chiefly mammoth hunters.

- The chert source materials used

by early Kincaid knappers (as well as the makers of

at least four of the five Folsom points) appear to

be local, indicating an intimate knowledge of the

landscape and environs. As with the faunal evidence,

this aspect also implies a less mobile lifeway than

previously assumed. This predominate use of local

materials has been seen at other Clovis sites, as

well.

- Kincaid was one of the sites to

provide samples for Willard Libby to use in his new

(at the time) radiocarbon dating experiments, although

the results were unsuccessful. Fortunately, a

tiny sample of charcoal from a chunk of travertine

later was successfully dated using accelerator mass

spectrometry. This sample helped establish an end-date

for the Zone 4 deposits at about 10,000 radiocarbon

years B.P. (or 12,000 years ago in calendar years).

The Loss of History

|

Lab results from dating a tiny

fleck of charcoal from Kincaid, using a revolutionary

new technique, established the travertine deposit

at 9910 radiocarbon years before present, or,

in calibrated calendar years, nearly 12,000 years

old. TARL Records. Click to enlarge.

|

A lump of travertine from Kincaid

was crushed to produce an uncontaminated sample

of charcoal, no larger than a fleck of pepper,

for AMS radiocarbon dating. The results indicated

it was roughly 12,000 years old.

|

Field school student Dee Ann

Suhm gets a close-up view of the articulated bison

limbs found just above Zone 4 at the rear of the

shelter. Her theory is that a bison, wounded by

Folsom hunters, died in the shelter, thus accounting

for the five complete Folsom points found there.

The bones are the only evidence of a Folsom-age

deposit to survive the destruction of the treasure

hunters. Suhm, who later married illustrator Hal

Story, went on to earn a Ph.D in archeology, become

a professor of anthropology at UT-Austin and,

later, director of TARL.

|

|

We can imagine a scene in the shelter 13,000

years ago when a Clovis craftsman, perhaps wielding

a heavy antler baton, struck blades off a small

chert core. Another worker may have refreshed

his hunting gear by pulling a broken black-glass

projectile point from a dart shaft and replacing

it with a newly made tip.

|

This heavily resharpened Clovis

point is made of local chert, as were most of

the other tools and knapping debris left by Clovis

workers at Kincaid. Click to enlarge and see drawing.

|

|

Kincaid is the only site with indisputable

evidence of Clovis-period construction, and there

is the bone of an extinct horse lying right on

top of the pavement.

-Mike Collins

|

Toolmaking debris from Zone

4. Kincaid was the first site to produce a Clovis

blade core (left) with other Clovis toolmaking

debris.

|

The obsidian base found in

Zone 4 near the articulated bison leg bones. The

point, untyped as yet but with Clovis affinities,

is unusual in several aspects. The obsidian material,

a black volcanic glass, has been traced to a source

near Querétaro, Mexico, some 600 miles

to the southwest.

|

Drawing of Kincaid Shelter

by Hal Story.

|

|

|

|

Four of the hundreds of artifacts dug out

of their original contexts at Kincaid Shelter by treasure

hunters. With the loss of context, artifacts lose their identity,

so to speak. Time frames are difficult to establish, except

through cross-dating with other sites, and no meaningful statements

can be made about the cultures who created them.

|

Michael Collins on reconnaissance at

Kincaid Shelter in 1988. The Paleoindian specialist, now

deeply immersed in writing up findings from the Gault site

in Bell County, Texas, still hopes to complete his analysis

of the Kincaid findings. He notes that, although all cultural

deposits were removed from the shelter, the artifact collections

and records are curated for posterity at the Texas Archeological

Research Laboratory at UT-Austin, ready for future analysts

to study and interpret using latest techniques and perspectives.

Photo by Thomas Hester. TARL archives.

Looking at the Kincaid collection today, it

is tragic to see that some of the most intriguing and potentially

informative specimens are labeled with the lot number "908-2"

and other numbers which signify, "provenience unknown."

What this has meant for researchers is that the items left

by prehistoric peoples camped in the shelter perhaps 12,000

years ago were unearthed and mixed together with those left

by shelter dwellers perhaps 8,000 or 5,000 or even 500 years

ago. For the most part, any meaningful connections among cultural

remains of the same time period have been lost.

While mixed deposits in archeological sites

are common, natural disturbances such as erosion or rodent

burrowing often are found to have been the cause. Prehistoric

people also disturbed earlier evidence simply by camping on

top of it, by recycling tools or stones from earlier hearths,

and by digging pits into earlier deposits. What archeologists

hope to prevent through continued education efforts is the

knowing destruction of historic sites by individuals who want

to collect a few more projectile points which, when separated

from their context, offer little insight into the people and

cultures who made them.

|

|