Young men gather around a vessel

of bright pigment in preparation for body painting in

this scene by artist Reeda Peel. In prehistoric times,

ocher pigment had many uses, whether for body adornment,

massive scenes on cave walls, or small painted pebbles—"portable

art." Although Kincaid Shelter had no preserved

wall art, investigators found decorated stones and evidence

of pigment production.

Click images to enlarge

|

Cut marks and shallowly drilled holes

have created an animal-like face on this hard, red ocher

nodule, giving it the shape and appearance of a small

totem, or other special symbolic object. TARL Collections.

Click to enlarge and see reverse.

|

|

Ancient artisans were at work at Kincaid throughout

much of its history. They selected flat pebbles on which to

engrave intricate patterns and make odd scratchings—designs

that puzzle us today and cause us to ponder their meaning

and significance. Some of the work is finely executed with

parallel lines, grids, concentric circles, cross hatching,

and other geometric patterns.

Other designs—particularly the marks on

red and yellow ocher cobbles—appear more random, as if

someone scratched the surfaces repeatedly and from different

angles. Unlike the engraved objects, these "scratched"

stones likely were not "works of art," as we understand

the concept, but rather the "ingredients" of art.

Scratching ocher stone with a sharp tool or crushing small

ocher nodules produces a fine, pigment-rich powder that—with

a few added ingredients such as animal fat—becomes paint.

Working with a brilliantly hued palette of reds, oranges and

yellows, artists could paint designs on hides, small pebbles,

and cave walls, as well as bodies and faces.

There are other odd stones at Kincaid that apparently

were used for more practical purposes. Several large, flat

pebbles have random marks suggesting that rather than pigment

extraction, the stones were used as a hard surface for cutting

soft materials. And a number of curious, small, flat limestone

pebbles appear to be unmodified, devoid of any markings at

all. The stones are chiefly Edwards limestone, which does

not naturally occur in the shelter (Anacacho limestone formation).

Clearly, prehistoric workers gathered these small pebbles

from the river gravels and brought them into the shelter.

Were these blank "canvasses" stockpiled for future

artistry? Or were some once painted with special designs that

have faded away with time and weathering.

As you look at the various types of stones,

below, perhaps you will have your own ideas about their meaning

and significance. As will become evident, the stones cannot

be neatly classified; some clearly were used for one or more

different types of practical tasks, while others were more

esoteric and served purposes we cannot know. For a closer

look, images can be clicked on to view enlarged versions and,

in some cases, the reverse sides of artifacts. In some images,

contrast has been heightened to capture more detail.

Many of the engraved and scratched stones as

well as a quantity of the pigment stones from Kincaid were

found in Zone 5, a few were from Zone 6, but there were many

others found in disturbed fill, making it impossible to infer

a relative time period for their production. Based on information

from other sites, however, it appears that art in many forms

was significant to prehistoric peoples, from the Paleolithic

painters of the Old World to the most ancient Texans.

All of the specimens shown are curated in TARL

Collections, available for examination by qualified researchers.

Engraved Stones

|

|

In This Section:

|

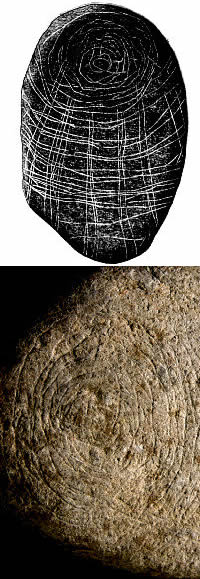

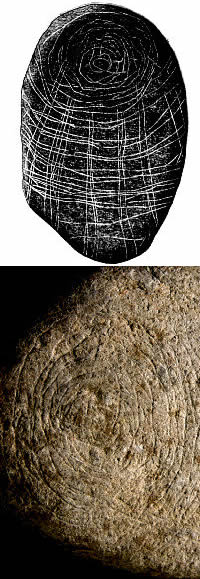

Like a medieval maze, the designs

on this palm-sized engraved stone form a tight spiral

of concentric circles. The pattern expands to a network

of rayed lines, as shown in the drawing above. This

motif, referred to as a spider-web pattern by some researchers,

appears on a number of both painted and engraved specimens

found in the dry shelters of the Lower Pecos region.

TARL Collections. Photo by Aaron Norment; drawing by

Hal Story. Click to enlarge photo.

|

|