The Gueiquesale (pronounced guey-kay-sally) were one of the large native groups

whose territory included the southern portion of the Plateaus and

Canyonlands. They are one of the many, lesser-known native peoples

who were a casualty of the calamitous changes during the Historic

period. In that sense, their story represents the fate of many native

groups who once roamed Texas: extinction and near oblivion.

Although the Gueiquesale actually may have occupied or ranged over

a much larger region, they are not discussed in Spanish documents

with any depth until the 1670s, when they began to solicit the help

and protection of the Spanish. By that time, the Apache were pushing

south off the Southern Plains due to Comanche intrusion into their

former homeland. In their wake, many native groups were also pushed

southward. Gueiquesale territory at that time was centered on the

general vicinity of modern Del Rio and north into the Canyonlands

as well as south into Coahuila.

Although much of the Plateaus and Canyonlands had not been explored

by the Spanish prior to the 1670s, word of unrest of various native

peoples in the general region had reached northern Mexican towns

in the 1660s. Some reports indicated that as early as 1658 native

peoples from north of the Rio Grande were asking the Spanish for

missions and presidios and actually petitioned the government to

settle close to Saltillo. The petition was denied, but it and other

requests prompted Father Juan Larios, a Franciscan friar, to travel

north toward the Rio Grande where he stayed for three years.

Upon his return, natives were again petitioning for settlement.

This time the petition included a number of groups (Babane, Jumano,

Bobole, Baia, Contotore, Tetecore, and Momone). The petition also

asserted that these groups would be joined by two other very large

groups: the Gueiquesale and the Tiltic y Maigunm.

One Gueiquesale was brought before the court. He testified that his

people wished to settle in pueblos (towns).

The motives of the petitioners are important in understanding subsequent

events. The smaller of these native groups said they needed to band

together with larger groups. Another factor was that several years

past some native peoples had aided the Spanish in battles against

the Cacaxtles and others. Likely, they were concerned about reprisals

from the Cacaxtles or allies of the groups that had been attacked.

They were equally concerned about the continuing Spanish raiding

of their rancherías for slaves. Although Spain’s official

policy outlawed slave raids, unofficially they continued. The native

people in the Plateaus and Canyonlands practiced a hunting and gathering

lifestyle, requiring them to move frequently from place to place.

Their small, temporary encampments (rancherías) left them

vulnerable to the raids. Living among larger groups would make them

less vulnerable, particularly if the settlements contained missions

and presidios.

Permission was given in early 1674 for the larger settlements to

be established in northern Coahuila. Priests, including Fray Larios

and Dionysio de Penasco along with Fray Manuel de la Cruz, and soldiers

under the command of Captain Elisondo, traveled north to northern

Coahuila where they founded two settlements. Santa Rosa de Santa

Maria was located on the Sabinas River. San Ildefonso de la Paz was

14 leagues (36 miles) north of the Sabinas and about 50 miles south

of Del Rio. Gueiquesale were the largest group at San Ildefonso,

numbering over 500, but other Gueiquesale were also among the natives

at Santa Rosa. These settlements were the first of several in this

general area, all aimed at bringing natives of northern Coahuila

and the Plateaus and Canyonlands south to live in settlements, learn

to farm, and become peaceful communities. Their successes and failures

over the next several years illustrate the reality was less than

desired.

Traveling north of the Rio Grande, the friars persuaded many groups

to go south and settle with them in the two settlements. As many

as 3,200 natives were reported living in clusters near Santa Rosa

in June of 1674. However, their presence had as much to do with the

large prickly pear fields that were also near Santa Rosa. Reports

from the friars state that the natives were eating the ripe prickly

pear tunas, but they also reported concern that the natives would

leave when the harvest was over. Their fears were well grounded.

Having no stores of food in the settlement, the natives and priests

left Santa Rosa to find other food. In their absence, natives destroyed

the settlement that same summer.

Other settlements and missions were established over the next century,

some ending like Santa Rosa, others having limited success. As late

as 1762, 26 Coetzales (Gueiquesale) were living at San Miguel de

Aguayo of Monclova. While the efforts of priests and soldiers to

establish settlements for the Gueiquesale and other groups did not

meet with the successes they hoped, they left behind a number of

Spanish documents with details about the Gueiquesale and their allies,

the foods they sought, as well as some details about their family

and spiritual lives. Those details are summarized below.

Alliances with other Native Peoples

Like other native peoples, the Gueiquesale had alliances with other

groups. Spanish documents are far from perfect in telling us about

those alliances, but the repeated presence of the Gueiquesale with

certain other groups (and not with certain other native peoples)

strongly suggest their friendship with them. Hence, we suspect that

they were close to the Manos Prietas, Babane, Jumano, Bobole, Baia,

Contotore, Tetecore, and Momone because these groups included the

Gueiquesale as among the peoples who wanted to establish settlements

in northern Coahuila.

In several documents from the 1670s, Don Esteban, a Gueiquesale

leader, appears to have been the leader of a coalition of people

who included the Gueiquesale, Manos Prietas, and no less than 22

other native groups. Leaders like Don Esteban were charismatic individuals

who tended to make decisions that enhanced the well being of the

larger group. When such a leader emerged, other, often smaller groups,

sought friendship with the leader’s group. During stressful

times, such allies could be called upon to come to their aid. Certainly,

the large numbers of groups under Don Esteban’s leadership

together with the Gueiquesale population estimates of more than 700

must have made his a fairly powerful and well-respected coalition.

Alliances among groups were not static. Like similar arrangements

among countries today, they shifted as situations changed. Reports

about Spanish efforts to settle the Gueiquesale document that another

group—the Yorica—sought an alliance with the Gueiquesale.

The manner in which this alliance was sought—cautiously through

an intermediary and with gifts—may represent the way alliances

were formed among different people in the Plateaus and Canyonlands.

In 1674, one of the priests pressed north of the Rio Grande to encourage

the Manos Prietas to move south. The Manos Prietas were already likely

allies of the Gueiquesale.

Earlier that year, Captain Elisando met with leaders of groups who

wanted to settle, and the Gueiquesale and Manos Prietas were among

those leaders. When Fray Penasco found the Manos Prietas in the Plateaus

and Canyonlands, they told him of another group, the Giorica or Yorica,

who lived just to the north. Here, the Manos Prietas acted as intermediary.

It is interesting that the Yorica first approached the priest rather

than the numerous Gueiquesale who, at that time, were enjoying the

prickly pear tuna fields near the Sabinas River. Perhaps this was

simply because the priest was there and interested in meeting new

peoples he could encourage to move into the settlements. On the other

hand, it may reflect the caution of the Yorica, a way to illicit

information about other groups yet still be able to retreat if necessary.

Regardless, Fray Penasco sent ambassadors to the Yorica. During

the ensuing diplomatic exchanges, they released to the Manos Prietas

a captive Gueiquesale boy. This was the gift. The

Yorica likely knew of the alliance between the Manos Prietas and

the Gueiquesale, and were told during the diplomatic exchanges the

Manos Prietas were going to travel south with the priest. Giving

up the captive boy was an offering of good will. The offering was

accepted and sealed by a ceremony to celebrate the boy’s return.

In the end, 300 Yorica traveled with the Manos Prietas to Santa Rosa

where they were peacefully settled among the other residents, including

the populous Gueiquesale.

Gueiquesale Life and Families

According to records written by the priests, the Gueiquesale subsisted on mescal,

tunas of prickly pears, acorns and other nuts, fish, deer and buffalo.

At one point the friars were out of food and ate the same sotol,

lechuguilla, and tule reeds as the natives.

When the Gueiquesale and their allies lived in the settlements,

they did learn to farm, successfully raising a few crops. However,

the settlements did not have the resources to sustain large numbers

of people indefinitely nor year round. Because of this, the people

would return to the settlements when crops were ready for harvesting,

then travel north to the Plateaus and Canyonlands to hunt deer and

buffalo or other resources during the rest of the year.

Spanish documents inconsistently report on the family lives of

native peoples. Each author reported on things that seemed important

to him. Thus, we glean information from small bits and pieces. For

peoples like the Apache, seen over a broad territory and a long time,

the small bits and pieces eventually add up to a bigger picture.

Not the whole picture, but certainly a better one. For the Gueiquesale,

the picture remains small, but it is tantalizing.

We know that the Gueiquesale were relatively numerous. Persons

pleading for native missions near the Rio Grande specifically say

that the Gueiquesale are one of two much larger groups. We learn

from another document that the settlements near the Rio Grande had

512 Gueiquesale there. Another document states that over 700 Gueiquesale

were in a camp north of the Rio Grande. Given their hunting and gathering

lifestyle, it is doubtful that all Gueiquesale families would move

en mass. The Chihuahuan desert in which they resided was limited

in resources and would have made such large camps difficult to feed.

On the other hand, when the priests traveled with them in 1674,

their reports suggest that smaller groups traveled parallel to one

another, separated by several leagues. Such a pattern would have

allowed them to keep in touch while finding sufficient food to feed

the people who traveled in the individual group. Each group moved

when local food resources were depleted. Seasons of plenty would

likely have encouraged many of these smaller groups to come together.

Such seasons would have been when prickly pear tunas ripened in some

of the areas where it grew in abundance and when the Gueiquesale

cooperated to hunt bison. In addition to providing sustenance, these

large group gatherings would have renewed friendships and other ties

that bound the Gueiquesale together as a unified whole.

We know that they cared for one another. When the Spanish tried

to settle the Gueiquesale into one of the Coahuila settlements in

1674, they declined because their people were ill and they wanted

to take them away to care for them. They promised to return when

the sick ones were better. The men showed great valor in battle.

When one of the priests, Fray Manuel, was concerned for his life

while he was north of the Rio Grande, Gueiquesale warriors came to

his aid, embracing him. Their scouts found the enemy group nearby,

and the Gueiquesale warriors declared to the priest they would die

before they would abandon him. Together, these actions suggest a

loyal, close-knit people.

Changing Worlds

The world of the Gueiquesale and other native groups in the Plateaus

and Canyonlands underwent drastic changes beginning in the 1600s.

We know that the Gueiquesale and their allies wanted the protection

and aid of priests and soldiers. While they clearly did not understand

the Catholic or other European religions, they did witness firsthand

native groups in Saltillo and other Spanish communities, finding some

measure of protection after ascribing to a belief in the European

religion. We also know that these groups were under increasing pressure

from the Apache advance south into their territories. Strange new

diseases, such as smallpox and measles, entered their territory at

the same time as these Europeans and those diseases killed their

friends and families.

We cannot fully understand how the Gueiquesale interpreted these

changes. But, we do know that several rock art panels in Val Verde

County show mission-like architecture. One has a stick-like European

figure in front of such a structure with his hands raised. Given

that it is generally believed that rock art represents expressions

of a group’s spiritual life, could these represent an effort

to reach out to this new religion of a people unaffected by the Apache

intrusion or the diseases? We may never know for certain, but these

rock art panels are few and unique.

Another aspect of spiritual life and tradition is provided in the

description of their battle with other groups. As described above,

when Fray Manual feared for his life, 98 Gueiquesale warriors led

by Don Esteban went to his rescue. Apart from their bows and arrows,

hide-covered shields, and a small loincloth of deerskin, they also

wore body decoration—streaks of red, yellow, and white across

their chests and arms. In addition, they wore headdresses made of

vines, mesquite leaves, and feathers.

Since we know that none of these body adornments would be used as

weapons, we must assume that either they were ways to ensure that

in a battle one could easily tell who was an ally and who was an

enemy, or they were ways to ward off death. Before the battle, the

priest showed the warriors a cross, or image of Christ, and told

them that God would help them overcome the superior numbers of enemies

they faced. When this same priest was taken to their ranchería,

a village of some 700 people, the Gueiquesale women danced to express

their pleasure at his visit. Apparently, this was their custom when

visitors they wanted to see came to their villages.

|

The Gueiquesale were also known as Coetzale, Gueiquesal,

Gueiquechali, Guericochal, Guisole, Huisocal, Huyquetzal, Huicasique,

Quetzal, Quesale, among other names.

|

The Rio Grande River near its juncture with the Pecos River. The area, near present-day

Del Rio, was the center of Gueiquesale territory in the 1670s, extending north

into the Canyonlands and south into Coahuila The towering cliff on the right

marks the mouth of the Pecos River canyon. Photo from ANRA-NPS archives at

TARL. |

Diary of Fernando del Bosque, who traveled into the interior of Texas with Father Juan Larios in 1677 to investigate unrest among native peoples. Photo courtesy of the Center for American History (Documents for the Early History of Coahuila and Texas: 2Q259-836, Vol.4, p.380). |

The native people in the Plateaus and Canyonlands practiced

a hunting and gathering lifestyle, requiring them to move frequently

from place to place. Their small, temporary encampments ( rancherías)

left them vulnerable to raids by the Spanish, who sought slaves

in spite of bans on such practices, and attacks by other native

groups. Living among larger groups would make them less vulnerable,

particularly if the settlements contained missions and presidios. |

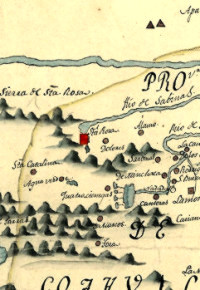

Settlements established by Spanish priests in northern Coahuila (Mexico) in the mid-1600s. Native peoples, including the Gueiquesale, sought protection by banding together into larger groups in "pueblos," or small towns such as Santa Rosa, shown with red dot. Click to enlarge. |

Ripening of fruits (tunas) of prickly pear cactus annually beckoned native peoples out of missions and settlements and into the fields for harvesting and celebrations. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Deaprtment. |

As many as 3,200 natives were reported living in clusters

near Santa Rosa ( Mexico) in June of 1674. However, their presence

had as much to do with the large prickly pear fields that were

also near Santa Rosa. Reports from the friars state that the

natives were eating the ripe prickly pear tunas, but they also

reported concern that the natives would leave when the harvest

was over. |

Cattails or tule reeds were used by native peoples both as a nutritious food source and as thatch for their shelters. One account of a Gueiquesale encampment |

At one point the friars were out of food and ate the same

sotol, lechuguilla, and tule reeds as the natives. |

Acorns, one of the many nuts and fruits harvested by native peoples on the Edwards Plateau. |

Seasons of plenty would likely have encouraged many of

these smaller groups to come together. Such seasons would have

been when prickly pear tunas ripened in some of the areas where

it grew in abundance and when the Gueiquesale cooperated to

hunt bison. In addition to providing sustenance, these large

group gatherings would have renewed friendships and other ties

that bound the Gueiquesale together as a unified whole. |

Desert lands in southwest Texas, with typical scrubby growth of lechuguilla and other arid-adapted plants. Native peoples, such as the Gueiquesale, were able to subsist in harsh conditions by moving frequently to other areas as fruits and nuts ripened and by roasting the hearts, or bases, of plants such as lechuguilla, sotol. |

An orange-red church and a lone rider in European garb, the work of an unknown historic-period native artist, loom from the shelter wall in a Lower Pecos canyon. Perhaps native peoples painted these and similar images as a means of recording events and to help make sense of a rapidly changing world. Photo from site 41VV343, TARL archives. |

|