Apache—without a doubt, the name

is one of the most evocative of all Indian groups, charged

with history and popularized in books and movies. However, the name

Apache is a generic one, applying to several tribes that have shared—but

unique—histories. The Apache include groups that have been

known at various times as Apachu, Lipan, Mescalero, Faraones, Gilenos,

Natagee, Querechos, Tontos, Ypandi, and Yutaglen-ne, to name but

a few.

Many federally recognized tribes in the United States today have

names that were given to them by Europeans or by other Indian groups

in early historic times. In some cases, Spaniards or other Europeans

assigned a name based on physical appearances, such as hairstyle,

or a cultural aspect of the group. In other cases, the first name

given a native people was based on a place. For example, Querecho was

the name given to the native people on the Southern Plains by the

people who lived in Pecos Pueblo who had close trade relations with

that group of Apache.

The term Apache dates from the year 1601 when Onate used the term Apachu to

refer to the people occupying the Southern Plains. The name was later

changed by the Spanish to “Apache,” but the name was

not universally used until the nineteenth century. Prior to that time,

both they and others used distinct names for their various groups.

Manuel Merino in 1804 wrote:

They can be divided into nine principal groups…. The

names…in their language [are]….: Vinienctinen-ne,

Sagatajen-ne, Tjusccujen-ne, Yecujen-ne, Yntugen-ne, Sejen-ne,

Cuelcajen-ne, Lipanjen-ne, and Yutaglen-ne. We have replaced these

naming them in the same order: Tontos, Chircagues [Chiricahuas],

Gilenos, Mimbrenos, Faraones, Mescaleros, Llaneros, Lipanes, and

Nabajoes [Navajos], all of them under the general name of Apaches.

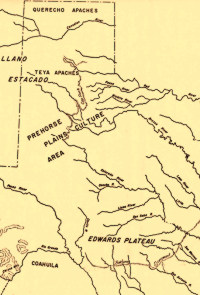

A number of Apache peoples have roots in Texas, but during the prehistoric period they lived in the northern Plains and Canada.

As they moved south, they did not settle in the Plateaus and Canyonlands

but, rather, in and around the Southern Plains of Texas, Oklahoma,

and New Mexico. While scholars dispute the route and timing of their

migration south there seems to be fairly clear evidence that the

Querechos and possibly the Teyas whom Coronado met on his march across

the Southern Plains in 1541 were Apaches.

As we can tell from their names, the Apache are not just one group

of people. Either prior to or shortly after their migration south,

they divided into eastern and western groups and both of these geographic

divisions subdivided further. Today they retain those same subdivisions.

The eastern Apache generally occupied the lands and areas of the

Southern Plains. Spanish documents make clear that subdivisions of

the eastern Apache existed from their earliest encounter with those

native peoples. We do not know, however, if these subdivisions were

an artifact of their movement to the south, where separate bands occupied

different regions, or if the subdivisions were a long-standing tradition. Eventually

some Apache names began to take precedence over the variety of earliest

appellations. Mescalero Apache, mentioned as early as 1725, and Lipan

were maintained, while Pelones, Natagees, and Fararones were less

frequently used and eventually disappeared from the documentary record.

The Apache in Texas began a gradual move toward the Plateaus

and Canyonlands during the late seventeenth century and were gradually displaced

by the Comanche as that group pushed them southward. Documents written

by Spanish military officers with many years of experience on the

northern frontiers and familiar with both the geography and the native

peoples in the region place the Apache in the area of the Plateaus

and Canyonlands by the eighteenth century. One of these military

men, Joseph de Berroteran, wrote that the Apache “came from

the Rio Puerco [Pecos] where it joins with the Rio del Norte [ Rio

Grande].” He warned government officials that, if the presidios

that had been established on the Rio Grande were not maintained,

the Apache would control the Rio Grande from El Paso to San Juan

Bautista (located between modern Eagle Pass and Laredo). Joseph de

Urrutia, another military officer, wrote in 1733 that the Apache

resided along the Pecos, frequently traveling east and west along

the Rio Grande.

The Apache, particularly the Lipan and Mescalero, had a major presence

in the Plateaus and Canyonlands in the early eighteenth-century period.

The westward movement of English-speaking settlers across North America

and the Spanish colonization of the Southwest combined to create great

unrest and turmoil among native peoples. As the Apache were forced

from the Southern Plains by the quickly-moving Comanche, they began

to align themselves with other native peoples, including the Jumano

and Tonkawa, groups with whom they previously had hostile relations

They also sought peace with the Spanish. Those peace efforts resulted

in the establishment of a Spanish mission, Santa

Cruz de San Sabá and

presidio at San Sabá and,

later, the two missions, San Lorenzo de la Santa

Cruz and Nuestra

Senora de Candelaria on the Nueces River, all during the mid-eighteenth

century.

Ultimately, the San Sabá mission was destined to fail because the

Spanish ignored—or were unaware of—the volatile relationships

among native groups. As Maria Wade notes in her 2002 volume on the Native Americans of the Edward Plateau, the Spaniards

made a significant error in establishing the mission :

At issue is the assumption of the Spaniards that they could

be friends with everyone regardless of Native internal enmities,

as well as the political arrogance of making new alliances without

informing former allies, especially when the new alliances were

made with their bitter enemies.

The mis-step by the Spanish led to an assault on the mission, orchestrated by Tonkawa, Comanche, Bidais, Wichita, and

Caddo Indians, all enemies of the Lipan and other Apache.

Mission San Lorenzo de la Santa Cruz, established in 1762, postdates

the disaster at San Sabá. Although it lasted longer, San Lorenzo

was never officially approved and was burned and then abandoned in

1771. Situated on the upper Nueces River at present-day Camp Wood, Texas, the

mission was founded to serve the Lipan Apache. Missionaries reported

that some 3,000 Lipan were at the mission; Spanish reports, however,

indicate that there was a regular coming and going of individual

bands of groups of Lipan. The priests sought to teach

the Lipan to grow corn and other crops. However, raids by hostile native groups plagued the mission and in 1771 it was

abandoned. Curiously, however, the Lipan and Mescalero continued

to frequent the area of this mission and Mission Candelaria in the century

to come, often to grow crops when they could not access other food

In the second half of the eighteenth century and after their mission

on the San Sabá was destroyed, the Apache ranged from the Bolson

de Mapimi to the Rio Grande to the Nueces. In 1772, 300 Lipan Apache

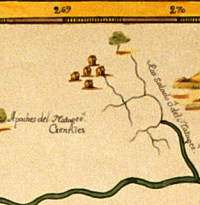

attacked haciendas and pueblos in Coahuila. A Spanish military map

dated 1773 continued to call the Pecos River the “Salado o

rio del Apache del Nataje que la Fora lo llama del Pecho y Danville

de los 7 Rios,” meaning “the Salty River or river of

the Nataje Apache whom Spanish engineer and cartographer Nicolas

la Fora calls the Apache of the Pecos and whom Danville calls the

Apache of the Seven Rivers.” On that same map, several other

Apache groups are shown in or close to the Plateaus and Canyonlands—the

Apaches Jumanes just north of the Lipanes and on the east side of

the Pecos, with the Natajes and Mescaleros depicted on the west side

of the Pecos. Two years later, Juan del Ugarte also noted their presence

in the region. Traveling north of Monclova some 740 miles in an effort

to force the Apache away from Coahuila, he found them on the Rio

San Pedro or Devils River. The Mescalero were, by the late eighteenth century,

roaming the Plateaus and Canyonlands, and Spanish armies repeatedly

found them between the Rio Sabinas, Piedras Negras, and the mouth

of the Pecos, either alone or in the company of Lipan, or other Apache

bands.

The Apache maintained a presence in northern Mexico in subsequent

decades, but the Lipan and Mescalero were often found in the region

of south and Central Texas, particularly on the Nueces, the

San Antonio, and Guadalupe river areas as well as the Colorado. Their presence

on the Pecos River can be well documented in the nineteenth century including

the area of Toyah Creek’s confluence with the Pecos.

The Apache presence in the Plateaus and Canyonlands was quite broad

during the nineteenth century. Manuel Merino, a prominent government

official in Chihuahua, issued a report on the Apache in 1804 that

describes their territory. He wrote that the Apache nation “inhabits

the vast empty expanse living between 20 and 38 degrees of latitude

and 264 and 277 degrees of longitude…to that of La Bahía del

Espiritu Santo.” Elsewhere, Merino described the territories

of the various Apache subdivisions:

[The Faraones] are still quite numerous. They inhabit the mountains

lying between the Rio Grande del Norte and the Pecos, maintain

a close union with the Mezcaleros, and make war on us. The two

provinces of New Mexico and Nueva Vizcaya have been and still are

the scene of their incursions. In both provinces they have made

peace treaties various times, but have broken them every time,

with the exception of a rancheria here or there whose faithful

conduct has obliged us to let them settle at the presidio of San

Elcerio [San Elizario]. They

border on the north with the province of New Mexico, on the west

with the Mimbreno Apaches, with the Mezcaleros on the east, and

on the south with the province of Nueva Vizcaya….[The Mezcaleros]

generally inhabit the mountains near the Pecos River, extending

northward to the edge of the Cumancheria. They approach that territory

in the seasons propitious to the slaughter of bison, and when they

do this, they join with the Llanero tribe, their neighbors….These

Indians usually made their entry through the Bolson de Mapimi whether

they are going to maraud in the province of Coaguila or in that

of Nueva Vizcaya….They border on the west with the Faraon

tribe, on the east with the Llaneros, and on the south with our

frontier of Nueva Vizcaya and Coahuila. Llaneros occupy the plains

and deserts lying between the Pecos and the Colorado…. It

is a very populous tribe, which is divided into three categories:

Natages, Lipiyanes, and Llaneros….[The Lipan] is probably

the most populous of all Apache tribes, and for many years it has

lived in peace on the frontiers of Coahuila and Texas.

|

Other names for Apache:

Apachu, Apaxches, Cuelcajen-ne, Faraones, Gilenos, Natagee, Natajee, Nataxe, Lipan, Lipanjen-ne, Mescalero, Mimbreno, Querechos, Azain, Duttain, Negain, Pelones, Sagatajen-ne, Sejen-ne, Siete Rios, Teyas, Tjusccujen-ne, Tontos, Vinienctinen-ne, Yecujen-ne, Yntugen-ne, Ypandi, and Yutaglen-ne

|

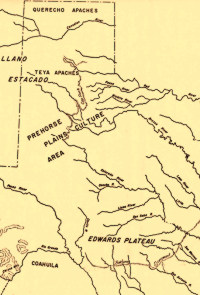

Southern Plains and southwest Texas in pre-horse times, showing location of early Apache groups, Teyas and Querecho, in Panhandle area. (Map after Newcomb 1961: Map 2.) |

Lipan Apache brave wearing breastplate. Watercolor by Frederich Richard Petri, circa 1850s. The artist lived in the area of Fredericksburg, Texas, and was on peaceful terms with many of the native peoples. |

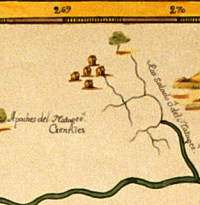

Rancherias of the Natagee, an early Apachean group, are shown in a 1729 map of Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Texas in 1729, drawn by Francisco Alvarez Barreiro. Note the Pecos River in west Texas is also identified as Rio de Natagee. Click to see larger image. |

|

Documentation of Apache Groups in

Plateaus/Canyonlands in 1700s

(View full table)

| Source |

Description |

| Jesuit Priest |

Apaches Fahanos [Faraone] are present north of the Rio Grande

on the Pecos River; Apaches Necayees [Natajee] are east of

Pecos Pueblo in the Southern Plains |

| Joseph Vargas |

The salines near Hueco Mountain are “lands of the

Apaches" |

| Map |

Pecos River is called “rio salado o del Natagee” meaning “salty

river or the river of the Natagee people” |

|

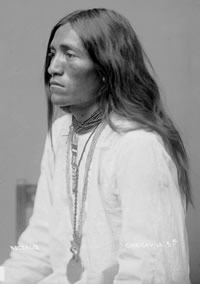

Hattie, Chiricahua Apache, circa 1899. She is wearing traditional hide clothing, with added brass tinklers at neckline, and bone and shell bead necklaces. |

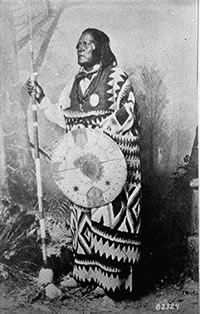

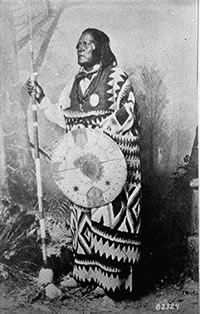

San Juan, a Mescalero Apache chief. National Archives. |

|