Texas Beyond History

Field Investigations and Findings

Archeologists found artifacts and burned rock features representing prehistoric camping activities along Hackberry Creek from roughly 6200 to 300 years B.P. (before the present ). The most recent materials, closest to the surface, were left by people from the Late Prehistoric Toyah interval. The oldest cultural traces were left by Early Archaic peoples. See full profile. |

|

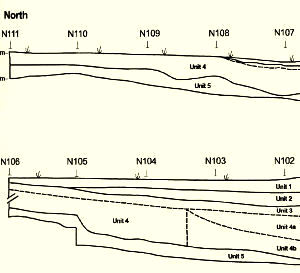

When archeologists began surveying at the Varga Site, they found traces of an occupation zone littered with burned rock west of the highway pavement. Multiple classes of artifacts, lithic debris, bone fragments, and burned rocks also were observed on the disturbed surface. Because the site appeared eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, archeological investigation was in order prior to the road improvements to determine the significance of the site and obtain a sample of the cultural materials present. A two-phase investigation strategy was implemented. Phase I consisted of backhoe trenching across the area and through what appeared to be the burned rock mound. This allowed TRC archeologists to assess the length, width, and depth of the feature and to assess its potential for answering important questions concerning these types of features. Limited excavations by hand were also conducted at that time to determine the presence and vertical distribution of smaller artifacts (i.e., tools, flakes, bones) and to determine the age and context of those materials. During this initial phase, it became clear that the site contained much more than just scattered camping debris; in fact, the burned rock was just one part of a major Late Prehistoric occupation zone. The limited test excavations defined multiple occupation zones on both sides of the pavement. Based on these findings, TXDOT ordered the Phase II data recovery effort to proceed. First, a research design was written by TRC and submitted and approved by TxDOT and the Texas Historical Commission (THC). This set the stage for the Phase II program. During this phase, investigations were much more extensive with hand excavations conducted in large blocks to target prehistoric camping activities on both sides of the pavement. Backhoe trenching to define the nature and extent of the natural and cultural layering was conducted across the first terrace, which contained the site. Trenches were also excavated in the terrace above and below this to help determine the sequence of the flood deposited sediments that had accumulated over time. Hand excavations in 1-by-1 m units were conducted on both sides of the pavement in large block areas that ultimately covered more than 200 square meters. The hand excavations yielded evidence of a complex layering of four distinct zones representing sporadic camping events along Hackberry Creek from at least 6200 to 300 years before present (B.P.). The four layers were later determined to represent four major archeological time periods: the Early Archaic, the Middle Archaic, the Late Archaic, and the Toyah interval of the Late Prehistoric period. The artifacts and features representing these prehistoric activities had been buried in sediments deposited by numerous repeated flood events, similar to the ones that destroyed the road. Silt and gravels carried by the floodwaters had covered over the different campsites through time. In some instances, the flood deposits provided a fresh surface on which the next grouped camped. In other instances, the previous camp was left partially exposed, causing the most recent camping debris to be mixed with the older camp garbage. For archeologists, this meant that the occupation zones "sealed" by flood sediments likely represented a narrower time frame and perhaps even a single camping event. Other more mixed deposits likely bore the evidence of multiple visits and activities in the same area, perhaps by several groups of people. Across the site, archologists found that the artifacts and other occupational traces extended horizontally from the southern edge of the first terrace to at least 50 m (roughly 55 yards) to the north. The depth of the cultural material was greatest in Block A and ranged from 100 to 150 centimeters (ca. 40 to 60 inches) below the surface. Hand excavations in Block A yielded a sample of cultural material from each of the four time periods. As shown in the profile graphic above, the layering across Block A was not perfectly flat. Some wedge-shaped zones were present that tapered away from the stream. Block B targeted only the youngest (Toyah interval) materials closest to the surface. The lower, older, materials were more sparse and appeared more disturbed or mixed than those of similar age in Block A. Parts of each excavated block had been tunneled into by rodents, causing some disruption to the layered occupations and potential movement of the smaller artifacts. The findings from each of the four major time periods represented are briefly summarized below. These are discussed in order, from youngest to oldest. Late Prehistoric: Toyah IntervalThe Toyah interval zone was rich in artifacts. Some 65,000 objects were recovered, including small waste flakes from their chipped-stone tool manufacturing (roughly 26,000 pieces), quantities of highly fragmented animal bones (about 18,700, most of which were from bison), thousands of small burned rocks used in their cooking activities, nearly 2,000 formal and informal chipped stone tools, just over 100 ceramic sherds (representing a minimum of five vessels), and 11 clusters of material identified as burned rock features. Fourteen accepted radiocarbon dates place the timing of the Toyah camping event(s) to between 290 and 660 B.P. Among the artifacts were some 215 arrow points. Type Perdiz—considered the hallmark of this late interval—predominated, but other types such as Cliffton, Scallorn, Guerrero, Edwards, Cuney, Bonham, and Harrell also were present. Thirteen older, Archaic-era dart points (Frio, Baker, Merrill, and untypable fragments) found in this component may have been stratigraphically displaced or picked up from the surface by Toyah campers. Other stone tools included scrapers, drills, bifaces, unifaces and edge modified flakes, and tool rejuvenation flakes, attesting to a wide range of activities at the site during the Toyah occupation. Of the four periods represented at the site, the Toyah component was the most intact and had the greatest degree of artifact preservation. The charcoal from the campers' fires, burned seeds from spills in their kitchens, and animal bones from their foods were generally preserved. Occasional pieces of older cultural materials were mixed in with the Toyah artifacts by rodents digging their tunnels into the deposit. Thus, the rodent activity tended to blur some of the horizontal patterning left after the last camping activities. This reduced our ability to clearly identify specific tool-making and other activity areas across the two excavation blocks. Nonetheless, analysis of horizontal distributions of artifacts seems to indicate that the component was reasonably intact. Further, the spatial patterning among artifact categories appears to be reflective of the camp as the campers left it, more so than disturbances that occurred after their departure. In general, this area served as a major campsite as revealed from the multiple cooking hearths and wide distribution of diverse camp debris. In one area the Toyah occupants dismembered animal carcasses and smashed the bone to retrieve the marrow from the bone cavities, in other areas they produced chipped stone tools and used them in a wide range of cutting, scraping, drilling, and boring tasks. Foods were prepared and cooked, and pottery was made and used. For meat, primary focus was on bison but a diverse range of other animals and plants were consumed, including deer, antelope, rabbit, bird, turtle, fish, snake, mussels, agave, prickly pear, and other desert plants, nuts, and seeds. They stayed here for a relatively lengthy period as indicated by the cleaning of the primary work areas at the campsite and dumping of their trash and no longer useable materials into specific disposal areas. This type of cleaning activity would not have been necessary in overnight or two- to three-day stays.This Toyah component is remarkably similar to most other excavated Toyah sites/camps across much of central Texas and fits within the Classic Toyah concept. Based on the presence of several artifacts that are non-local in origin (a clay figurine-like object, a Padre type arrow point more typical of the coastal region, a Harrell point associated with the Garza complex hundreds of kilometers to the north, marine shells from the Gulf coast, the Toyah campers may have moved or traded across a broad region. In contrast to the cultural connections indicated in the non-local objects, however, Toyah potters appeared to have used primarily local clays for their vessels, a finding which suggests a more-limited procurement area. Chemical analyses through neutron activation (NA) also indicated the clays were not the same as those used in making most pottery recovered from Central Texas sites. Local cherts also were favored for tool manufacturing. |

|

Late Archaic

|

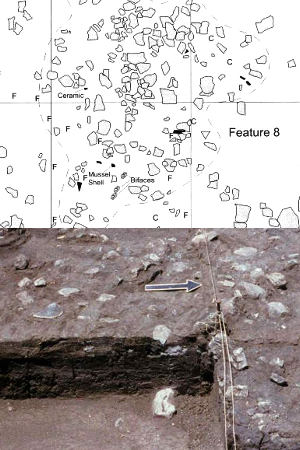

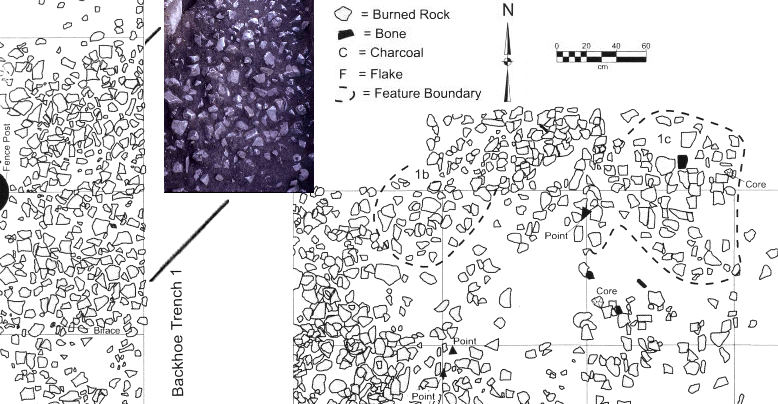

| The Late Archaic component consists primarily of one large, nearly 6-m diameter lens of burned rock with a shallow central basin. Resting on a stable surface and largely intact, this large buried feature had poorly defined margins of scattered burned rock and had been disturbed during backhoe trenching during Phase I. The feature is interpreted as an incipient, or early stage, burned rock cooking oven. Had this cooking spot been used over and over again, it might eventually have become a larger, more massive burned rock mound, or midden. Four small rock clusters identified within the boundaries of the oven feature represented the dump areas, where the Late Archaic cooks discarded burned rock that had become too small and fractured to retain sufficient heat for cooking. Plant remains from the feature included a few burned prickly pear seeds, a burned mesquite seed, burned walnut shell, and burned agave leaf fragments. Though sparse, these materials suggest the oven was used for the preparation of bulk plant foods that require lengthy cooking. This interpretation also is supported by lipid residues, or fatty acids, indicative of high-fat plants which were extracted from the burned rocks. Beyond the ill-defined boundaries of the large burned rock feature, the Late Archaic period occupation area was somewhat difficult to discern. Material immediately around and within the burned rock feature was relatively limited in quantity, but included sparse lithic debris (roughly 1800 pieces) from stone tool-making, a few mussel shell fragments, five other isolated burned rock clusters, some scattered burned rocks, and a small number of chipped-stone tools. Identified dart point styles associated with this burned rock include Frio, Marcos, Ensor, Castroville, and Edgewood. Although these types frequently are associated with bison hunting, bison bones were not present in this camp. The different projectile point types may indicate different groups of people with different backgrounds gathered to conduct bulk processing of a targeted plant food and resharpen or otherwise rejuvenate their chipped-stone tools. The component was radiocarbon dated by 11 accepted dates to a 600-year period between 1700 and 2310 B.P. Middle ArchaicThe Middle Archaic component was neither extensive nor well-defined, but was definitely present, indicating campers had used this site, perhaps only once, during the interval. Except for the compressed northern end of the deposit in Block A, this somewhat dispersed, wedge-like layer of material was separated from and below the Late Archaic materials, and was segregated above the older Early Archaic materials. The artifacts from this interval were vertically distributed over a 20 to 40 cm thick zone. Some 6,000 pieces were recovered, dominated by debtage, the waste flakes generated from the making of chipped-stone tools. Other materials included butchered deer bones, scattered burned rocks, and only 25 formal chipped-stone tools, among which were a number of Early Triangular projectile points. Two poorly organized burned rock clusters were identified and documented. The preservation of animal bone is rare in sites of this time period; thus the recovery of deer bone along with remains of rabbit, and possibly bison, though sparse, is significant. Had these bones not been burned, they likely would have decayed and disintegrated. Three radiocarbon dates—two on wood charcoal and one on a deer bone—directly date the Middle Archaic occupations to a 900-radiocarbon year period between 3910 and 4820 B.P. These three absolute dates are older than the Late Archaic materials above and younger than the Early Archaic materials below. Although the Middle Archaic is not well-known from other excavated sites, the material remains are not significantly different than those of other hunter-gatherer camps, except this group preferred unnotched projectile points. This is a key distinctive trait of this one group. Early ArchaicThe Early Archaic materials were situated within a roughly 30-cm thick zone, resting right on the much older river gravels. This position may indicate that the occupants camped directly on a gravel bar of the creek. With roughly 135,000 pieces, the component was extremely rich in artifacts. Materials varied in depth below the surface from a shallow 50 cm at the north end to a much deeper 120 cm in the southern end of Block A. Materials of this age are neither frequently encountered nor thoroughly investigated, and therefore are quite important. Some 170 dart points were recovered from this zone and classified as types Early Corner-Notched, Bandy, Martindale, Gower, Baker, and Merrell. These varied dart point types, along with a diverse array of stone tools (some1,300 pieces including bifaces, scrapers, drills, etc.), undoubtedly represent multiple, short-term camping events that have become mixed over time. Besides the chipped-stone tools and waste flakes, nine clusters of burned rocks were uncovered. These included two mostly intact hearths, two apparent dumps of burned rocks, and five general clusters of burned rocks. Bones, charcoal, and other organic materials were not preserved in this zone. Only a few scattered fragments of animal bones, a few burned prickly pear seeds, and a couple of wood charcoal pieces were recovered. Fifteen radiocarbon dates on animal bones, burned seeds, a snail shell, and plant particles yielded radiocarbon dates that document a minimum use period of 1,080-radiocarbon years from 5200 to 6280 B.P. Older events may be represented by these materials, but poor preservation may have destroyed the older organic material. A variety of data from this component indicates that the environment was somewhat cooler and wetter that other periods represented at the site as well as others in the region. During this time period, the Varga site and its surroundings may have provided a greater abundance of plants and animals, causing campers to return repeatedly to the area. Sampling and Laboratory AnalysesIn addition to chipped-stone tools and bone, a quantity of burned rock, soil samples, and other materials were collected from each of these occupation zones for specialized analyses. These technical studies, conducted on a wide variety of materials and samples, provide a wealth of insights into prehistoric activities at the Varga Site and are the subject of the following section: How Do We Know That?

|

|