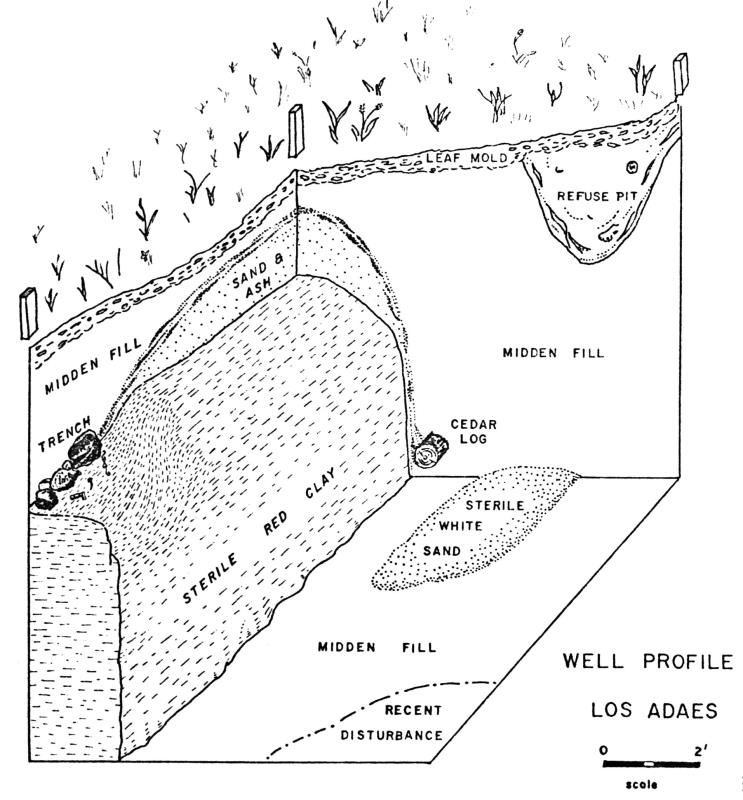

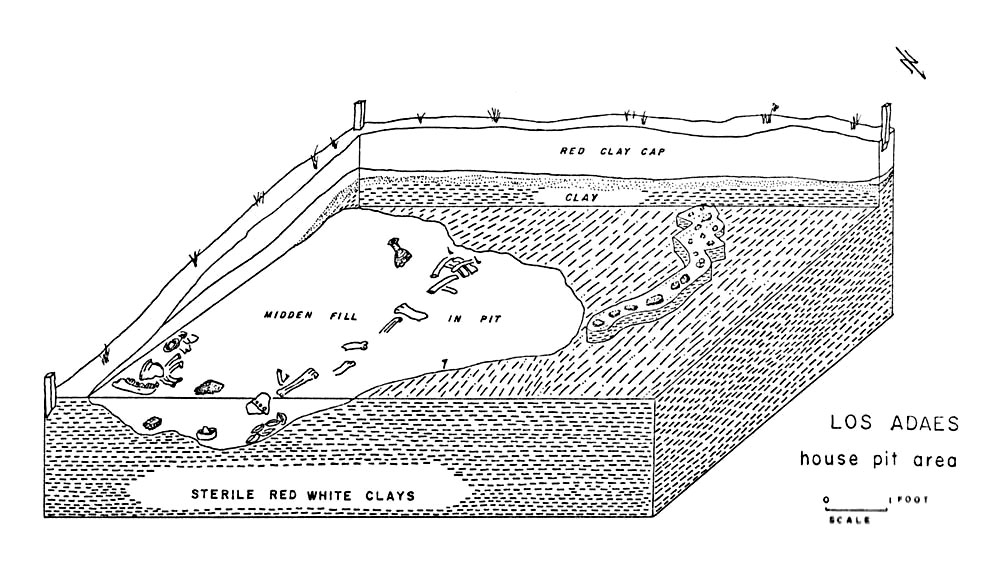

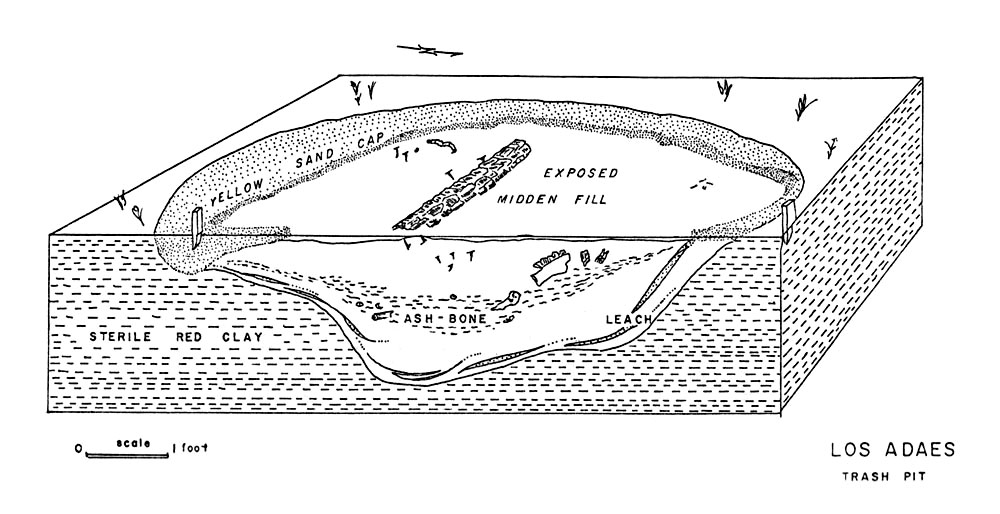

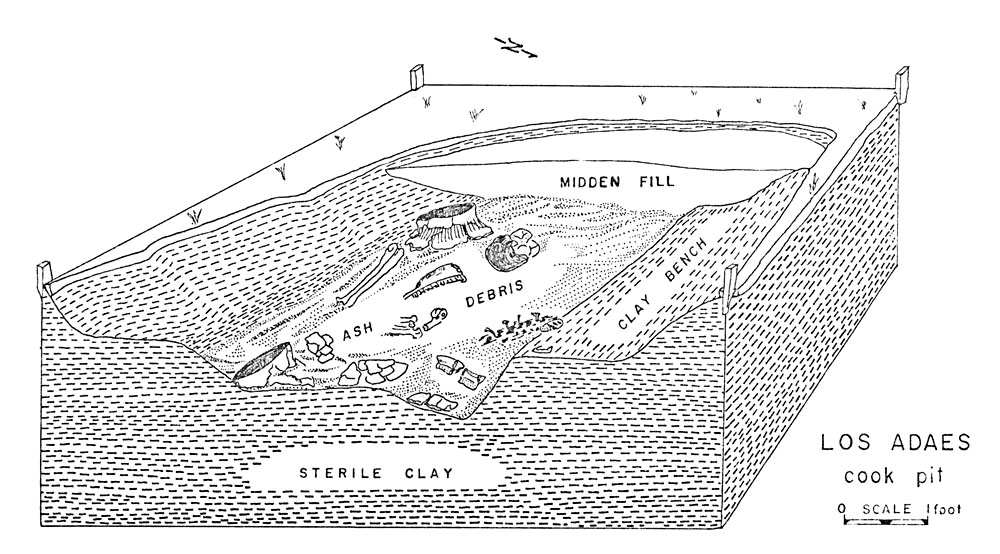

Archeological Investigations at Los Adaes

Feature drawings from Gregory's 1973 dissertation. Enlarge each to see details. | |||

|

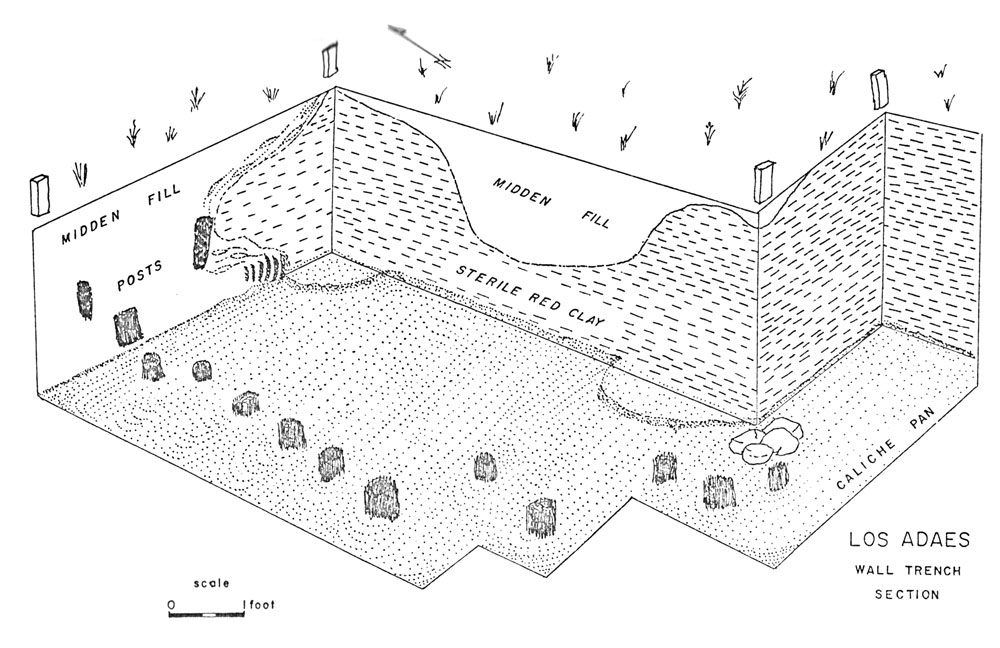

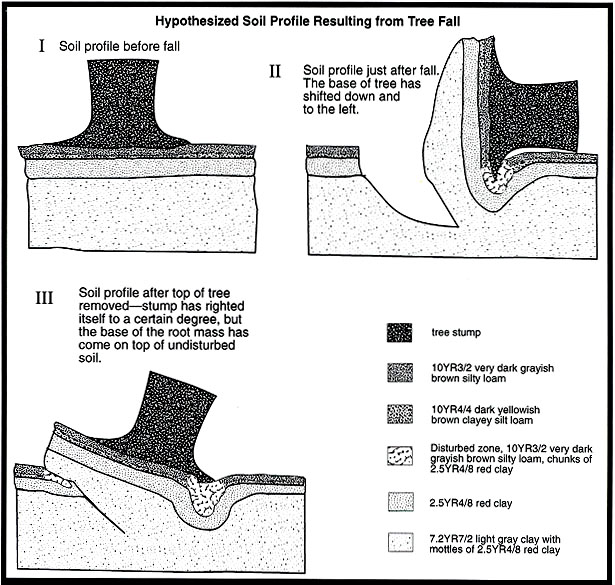

Gregory began teaching at nearby Northwestern State University (NSU) in Natchitoches and recruited students to help with additional fieldwork in the summers of 1968 and 1969. Concentrations of artifacts exposed along the roads and encountered in test pits were excavated to locate and document architectural features. Some 30 excavation units were dug, most being 5-x-5 foot squares, several of which were placed together to form small blocks up to 20-x-20' to more fully expose structural traces. (At the time, most American archeologists still based their excavation controls on the English measurement system, feet and inches.) Six architectural features were documented including the aforementioned trash pit, a house pit, a cook pit with large pieces of five Caddo pots, a well located within the presidio's southwestern bastion, a segment of the stockade trench, and part of the governor's house. The 1967-1969 work demonstrated that the hill was indeed the spot where Presidio Los Adaes once stood. Gregory's analysis of the rich assemblage of recovered artifacts and of exposed architectural features was reported in his 1973 dissertation, Eighteenth-Century Caddoan Archaeology: A Study in Models and Interpretation. The first period of archeological investigation at Los Adaes showed that its extensive, well-preserved archeological deposits had potential to tell much more of the Spanish capital's story than could be pieced together from archival records alone. A secondary goal of the first period of archeological investigation at Los Adaes was to get the site listed on the National Register of Historic Places to help preserve the site and call attention to its importance. Toward that end Gregory continued to monitor the site in the 1970s to make surface collections and document features that were exposed by road maintenance and erosion. He also enlisted the interest and aid of the administration at Northwestern State University and of civic leaders in Natchitoches. Los Adaes was a very important local landmark whose significance was scarcely known to most Americans. Finally in 1978 the site was listed on the National Register. 1979-1986:In 1979 Natchitoches Parish turned the park property over to the Louisiana Office of State Parks. Over the next six years (1979-1984) the state of Louisiana sponsored a series of intensive investigations under the direction of Pete Gregory as the state park was developed and enlarged. The investigations were carried out with grants from the Louisiana Division of Archaeology and the Louisiana Office of State Parks. The work was designed to pinpoint areas were architectural features and cultural deposits were preserved so as to protect them and avoid impact by the planned construction of a museum and related park facilities. With modest funding over successive field seasons and access to a larger area, Gregory was able to delineate the outline of presidio and document many structural features including water wells, two of the presidio's defensive bastions, palisade trenches, trash pits, and several different kinds of houses, some within and some inside and outside the presidio. Following evolving archeological convention in the United States, Gregory changed the grid and excavation controls to the metric system. The basic excavation unit was now the one meter square (1-x-1 meter), although larger units (such as 2-x-2 meter squares) were also used to expose major architectural features that covered extensive areas. Smaller shovel tests and auger probes were also employed. In many areas of the site only relatively shallow excavation were needed as most features lay within a few feet of the surface. Deeper features such as wells and wall trenches were encountered and sampled. The investigations also included basic survey and mapping with the goal of delineating those areas of the site that lay outside the park boundaries and these were targeted for acquisition. The state-sponsored investigations were followed by a 1986 NSU field school, again directed by Pete Gregory. This work focused, for the first time, on Mission Hill. Nine test pits and four shovel tests were excavated. Two units placed within what was thought to be the main mission building found structural evidence and exposed a linear stain suspected of being a burial, which was not excavated. 1993-2005In 1993 a severe wind storm, likely associated with a tornado, knocked down almost 100 trees at Los Adaes, and damaged a small visitor's center then under construction. As the larger trees toppled over, their root masses ripped up large chunks of earth, exposing and uplifting 18th century deposits in many areas of the site. As the fallen trees were removed, the stumps of the larger trees were left intact, some still toppled over and others which were partially righted as they settled back into their holes. Large, essentially intact blocks of soil remained around the some of the stumps. The archeologists took advantage of the opportunity represented by the wind-storm destruction and used the stump blocks as sampling units. Pete Gregory and students from his 1993 field school made collections of exposed artifacts in various tree-torn areas of the site and identified some of the most promising localities. Over the next decade Los Adaes Station Archaeologist George Avery and volunteers carefully excavated select stumps using systematic techniques including water-screening through fine mesh to capture tiny artifacts (such as seed beads) and animal bones. For an illustrated example of the excavation and documentation of one of the stump blocks at Los Adaes, see Stump 3. During this period Avery and Gregory used the Urrutia map to guide testing and interpretation. They demonstrated that the 1767 map was remarkably accurate as a snapshot of Los Adaes. But they also showed that the archeological record contained clear evidence of earlier structures and of subtle details that are not shown on Urrutia's map. At the end of 2005 the Los Adaes Archeological Station was closed by the state of Louisiana due to the budgetary crisis caused by Hurricane Katrina. This unfortunate development brought a sudden halt to a very productive ongoing research program. The archeological investigations at Los Adaes have literally and figuratively "barely begun to scratch the surface." The work to date has the demonstrated that the relatively well-preserved deposits present have potential to answer many remaining questions about the history of the site, its evolution through time, and, most importantly, about the interactions among the peoples whose intertwined lives make the Los Adaes so significant. |

|