Mexican Border after 1821

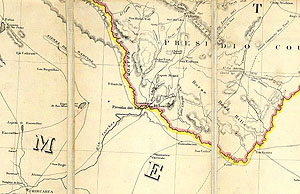

The main La Junta community in the mid-1800s was the border town known as Presidio del Norte (today's Ojinaga), although the Spanish fort had long since been abandoned. The only fortified locality was the Fort Leaton trading post. 1854 map by Henry Lange published in Berlin. Source: David Rumsey Map Collection. |

|

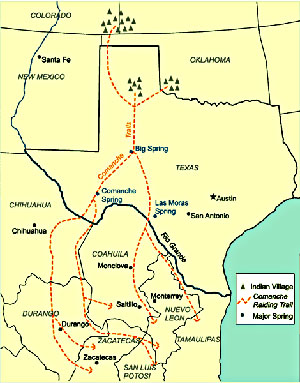

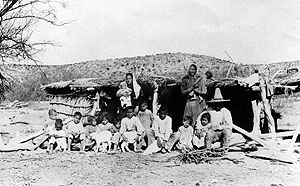

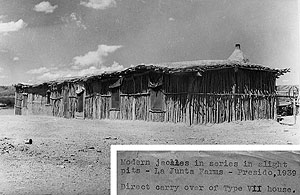

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the northern states remained neglected and peripheral to the central government. The small La Junta settlements on the remote northern border were no longer populated by distinct native groups, but by communities of mainly poor peasants of mixed heritage. Most survived by subsistence farming along the rivers. The peaceful relations that had existed with the Comanches came to an end and those with the Apache were further strained. The Mexicans attempted to keep the Apache in peace settlements, but in 1831 rations for these were cut off and soon thereafter relations between the two groups were severed. Apache groups returned to raiding. Soon afterwards, Chihuahuan authorities entered into an agreement with the Comanches. This accord allowed the Comanches a right of passage through the state in order to raid other Mexican states, an indication of the extreme provinciality that existed during the period. In return, the Comanche would continue to wage war on Apaches whenever they were encountered. Despite this agreement, Comanche incursions are reported to have continued in the region, although apparently not at the level achieved by the Apaches. The Comanche War Trail, a trail used by raiding Comanches on their way to and from the Southern Plains and Mexico, is thought to have passed through Comanche Springs in the modern town of Fort Stockton, southward through Persimmon Gap in Big Bend National Park, and then separated into several trails that crossed the Rio Grande and headed to different settlement areas in Coahuila and Chihuahua. The Mexicans' successful revolution against Spanish rule opened a new era of international trade along the famous Santa Fe Trail, which ran from Independence, Missouri, into northern New Mexico. From Santa Fe, the trade extended south through the Presidio del Norte at La Junta, and on to Chihuahua City. When the United States and Mexico went to war in 1846, one of the U.S. Army's invasion routes into Mexico followed the Santa Fe-Chihuahua Trail. After three years of war, the United States in 1848 obtained the land west of the new state of Texas-the territory comprising the modern states of New Mexico, Arizona, and California. As word of discovery of gold in California reached the east, exploratory expeditions and immigrant parties began to enter the Trans-Pecos in search of a viable route to the Pacific. Texas rangers John C. Hays and Samuel Highsmith attempted to map such a road, but became hopelessly lost. They probably were saved only by fortuitously stumbling upon a trading post known as Fort Leaton. Chihuahua Trail freighter Ben Leaton had purchased property near La Junta in 1848. He expanded upon existing structures to establish a home, trading post, and private fort. The Hays-Highsmith party recuperated at Leaton's place for 10 days before leaving for San Antonio. When they reached the city in December, 1848, they reported that they had found a practical wagon route from San Antonio to the Presidio del Norte. Trade became an important industry in the region in the next few decades as Anglo-Americans migrated into the area and established large ranches and facilitated the exchange of goods. An old trail between the Gulf coastal port of Indianola and Chihuahua City (by way of San Antonio and Presidio del Norte) began to see increased traffic at this time and became known as the Chihuahua Trail. This primitive road cut through Paisano Pass, in what later became Presidio County, and then traveled down Alamito Creek, with several forks eventually crossing the Rio Grande at Presidio del Norte. Freighters on the road typically used ox-drawn carts and were heavily armed to dissuade attacks. Another road, this one going from El Paso to San Antonio, crossed through the northern reaches of the region as trade became more and more important in the 19th century. While Texas' independence from Mexico in 1836 altered life at La Junta very little, relatively rapid changes ensued after Texas became part of the United States. Political boundaries in West Texas became more established and the Trans-Pecos was divided into El Paso and Presidio counties by 1850. A Comanche attack almost destroyed Presidio in 1849 and the following year Indians drove off most of the town's cattle. Major Jefferson Van Horne, Commander of Fort Bliss, recommended that an army post be established at Presidio to protect traders and travelers along the Chihuahua Trail. Instead Fort Davis was established some 80 miles to the north in 1854 to provide protection for inhabitants of the area and travelers on both the Chihuahua Trail and the San Antonio to El Paso road. (See Fort Davis and the Trans-Pecos Trails) In the late 1870s and early 1880s, railroads entered the region and settlement was encouraged by passage of the "Fifty Cent" law in 1879, which allowed sale of unappropriated lands at 50 cents an acre throughout much of West Texas. By the early 1880s, ranches and farms sprang up throughout the area, encouraging more Anglo-Americans, as well as additional Mexicans and Mexican-Americans to settle in the region. A small community along the Rio Grande at the downstream end of the La Junta district sprang up by late 1870 and became known as "Polvo." Initially occupied by Mexican-American homesteaders, the community consisted of a pueblo (village) with a central square surrounded by connected adobe houses with doorways opening to the inside of the square. This arrangement is thought to have been abandoned some time around 1900, at which time the community became more dispersed. At some point its name was changed to Redford. The local farmers organized an irrigation ditch association in 1876 to develop a system to irrigate their fields. The earliest dams in the area, known as presas de burros y muertos or burro dams, were constructed in several places along the river by farmers. Lengthy gravity-flow canals or acequias, brought water to the farmland. Some of these dams still hold water used for irrigation farming on both sides of the Rio Grande in the Redford Valley. The 1890s brought several changes to the area. A severe drought during the first portion of this decade greatly affected the ranchers of the area, a reminder to the early settlers that the region is within the Chihuahuan Desert and subject to extreme fluctuations in rainfall. At this time, mining had become an important industry in the region, with the Shafter district in the Chinati Mountains and, a few years later, the Terlingua district, providing the largest contributions. A large number of Mexican workers were employed in each of these districts, which helped shape the ethnic mixture now seen in the region. Also at this time, federal troops stationed in the area were reassigned as part of the army's efforts to consolidate its frontier garrisons. The fort at Fort Davis was abandoned in 1891, and, during this same year, the Seminole Negro scouts at Camp Neville Springs (now located in Big Bend National Park) received orders to relocate to Polvo, along the banks of the Rio Grande. While some have associated the presence of Buffalo Soldiers at Polvo with the name of a small community across the river—El Mulato—several new sources of information indicate that name was associated with the village over 100 years beforehand. The drought was broken in 1895, and ranchers again stocked the range with cattle, sheep, and goats-the next prolonged drought would not come until the 1930s. During the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920, the La Junta area would once again enjoy fame. The unrest that enveloped Mexico spilled across the river at times during the struggle for political and social reform. During this period U.S. military operations were greatly increased along the border. Newspaper reporters and cameramen also made Presidio their headquarters. During the 1914 Pershing expedition in search of Pancho Villa, Presidio even served as an emergency landing field for the first U.S. planes to engage in foreign combat. U.S. Cavalry troops were stationed along the Rio Grande at Ruidosa 35 miles above Presidio, Camp Fulton at Presidio, and Camp Polvo immediately east of the old town of Polvo. When the Mexican Revolution ended in 1920, the La Junta area once again lapsed into obscurity. Severe droughts in the 1930s and 1950s again devastated ranchers in the area, driving some out of the business, while others moved in to take advantage of lower land values. During this time, the government purchased a number of ranches in Brewster County and formed Big Bend National Park, which began operations in the 1940s. In 1988, the State of Texas purchased a vast tract in Brewster and Presidio counties located west of Big Bend National Park. Big Bend Ranch State Park is the largest holding in the state park system, and the southern part of it lies within the La Junta district. In sum, relatively rapid cultural changes occurred in La Junta and throughout the entire region during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Spanish interests revolved around settling the region and pacifying the Indian groups that raided frontier as well as interior settlements. Mexico and the United States inherited the same difficulties and hardships that Spain had in this rugged region-problems that continued until the early 1880s. At that time the Apaches, the last tribe at war with these countries, were subdued and most were removed to distant reservations. Since the late nineteenth century, a unique border culture has evolved in the La Junta district, a culture with distinctive languages, foods, art, customs, and lifestyles. Here one finds a peculiar blend of lingering aspects of traditional native cultures with newer ways introduced by the peoples who have come to the region during the historic era. Within the La Junta area border culture, cultural elements can be traced to Indian, Spanish, Mexican, Anglo-American, and even African American roots. The green-banded rivers continue to shape life and draw outsiders to the rugged arid landscape of La Junta de los Rios, a place still largely isolated from the modern world by its remote setting in the sparsely settled borderlands amid the Chihuahuan Desert. |

|