|

After its native people revolted and forced the missions to close in 1689 in protest of Spanish slave raids for the silver mines, La Junta was not visited again by Spanish officials until 1715. Then an entrada led by Sergeant Major Juan Antonio de Trasviña y Retis arrived to try to reestablish the missions. Trasviña y Retis was:

...pleased to see Indians with such good reason and so polite without having had any education and also to see them so well-dressed, men as well as women, the chiefs and their wives being outstanding with better clothes in the Spanish fashion, with shirts of fine white linen worked in silk. Some had skirts of serge, silk shawls, Cordoba shoes and imported Brussels silk socks. I found men, women and children with good natured, happy faces, who were very sociable with the Spaniards as they came and went all day long in the house where I was stopping.

The native people of La Junta had long been cultivating European crops, and by this time they had also begun to adopt aspects of European dress, tools, irrigation methods, architectural features and the Spanish language. In other words, the native peoples of La Junta were becoming assimilated into the Spanish colonial world. European disease and the slave trade had taken their toll, and the native population had been reduced to only about 2,100. The jacal churches from previous years were still standing, but in need of repair, so Trasviña urged the people to build adobe churches and a monastery. Two weeks later, the party left La Junta, leaving Father Gregorio Osorio and Father Juan Antonio García behind to run the missions.

Upon return to Parral in southern Chihuahua, Trasviña suggested to Viceroy Marques de Valero that permanent missions be established at La Junta. Responding to Trasviña's suggestion, Valero sent six additional priests to La Junta in 1716 along with herds of sheep, goats and cows. The priests founded five missions that year and one the following year. Trasviña personally supplied the missions with seeds, tools, clothing, and livestock as well as weekly food rations of beef, wheat, and corn.

In 1718, the people of La Junta again revolted in protest of continued Spanish slave raids and drove out the missionaries. In response, the missionaries petitioned Valero for a presidio to protect La Junta, but the viceroy denied their request. The missions reopened later in the year, but had to be closed again in 1725. The missionaries again petitioned Valero for a presidio in 1726 and he approved, but had to suspend the order the following year due to a lack of funds. Until 1732, the situation at La Junta was so unstable that the missionaries could no longer permanently reside there and visited their converts for only a short period of time each year.

Between 1732 and 1744, the missionaries reestablished the previous La Junta missions, but these had to be abandoned yet again in 1744 due to raids by Apache and a new threat from the Southern Plains, the Comanche. Apache and Comanche groups vied for control of the Trans-Pecos and adjacent regions for much of the 18th century. Mounted raiding parties raided deep into Mexico through the remote Big Bend country, an extremely rough, expansive, and virtually unknown area along the Rio Grande between La Junta and San Juan Bautista de Coahuila called the Despoblado.

Father Juan Miguel Menchero visited La Junta in 1746 and again recommended that a presidio be established to protect the missions from further raids. He complained that the "missions are exposed to constant attacks and hostilities of the enemy without recourse to a presidio nearby or to any other safeguard to their lives."

In response, Viceroy Juan Francisco de Guemes y Horcasitas sent three separate, but interconnected entradas to La Junta in 1747 to evaluate the feasibility of reestablishing the missions and constructing a presidio to protect them. Captain Joseph de Ydoiaga's entrada arrived first and found that the native population of La Junta had further decreased to only about 1,450 due to crop failure and disease. Several of the outlying pueblo locations were abandoned, with the former residents relocated to nearby pueblos more centrally positioned as a means of defense against the raiding Apache and Comanche.

The first reason for their coming together was that their Apache enemies frequently attacked their small pueblos, so much so that they had killed four women who had gone out to gather tunas [prickly pear]. – Joseph de Ydoiaga

At one of these locales, the former pueblo of Tapalcolmes (the Polvo site), Ydoiaga reported seeing the ruined adobe walls of a church or chapel. The expedition also found two friars, one of whom claimed to have been at La Junta since 1730.

Meanwhile, the governor of Coahuila, Don Pedro de Rábago y Therán, launched his entrada and forged a trail through the mountainous areas of northwestern Coahuila, the lower Big Bend, and eastern Chihuahua before arriving at La Junta. He never met up with Ydoiaga, who was then reconnoitering up the Rio Grande, but visited a number of pueblos downstream and up the Río Conchos. Rábago did communicate with captain Ydoiaga via messengers, but disagreed with the latter’s assessment of the issues. Becoming impatient, Rábago left La Junta to search for gold and silver on the return trip back to Coahuila. Rábago recommended to Horcasitas that someone else be sent to La Junta to reestablish the missions and build a presidio.

Captain Fermín Vidaurre's entrada arrived in La Junta after Rábago's entrada departed and after being led to La Junta by Ydoiaga's men. Vidaurre met with Ydoiaga, but, like Rábago, he only stayed in La Junta for a few days. After returning to the Presidio de Mapimi in northern Durango, Vidaurre recommended to Horcasitas that the La Junta missions be reestablished and a presidio be built. Ydoiaga stayed in La Junta for three months and held a formal investigation to determine the best site for the proposed presidio. In the end, he recommended against it because the necessary elements needed to support a garrison—adequate lands for livestock and crops, as well as farmers—were lacking.

At the very least, it seems that it [the presidio] should be established where the land promises the assurance of the necessities of life and permits regular cultivation. But as it has been seen, recognized, and recorded, the contingent plantings made by the Indians in the small humedades left to them by the rivers' floods on their lands (which most times, or during the years when the water does not rise enough, hardly leaves them places to plant-as is the case this year) are not nor can they be sufficient. - Joseph de Ydoiaga

The efforts to reestablish the missions and build a presidio at La Junta were not renewed until 1759 when Father Lezaun made three visits to reestablish missions. Later that year, Captain Rubin de Celis, on orders of Horcasitas, sent a party of two missionaries and fifteen soldiers to determine an appropriate site for a presidio. They were enthusiastically received by the people of La Junta, who had grown weary of raids, but encountered opposition from Father José Páez, custodian of the Franciscan missions, who objected to having a presidio and soldiers in his jurisdiction. Celis ordered his party to return, but Páez was unable to counter Horcasitas' decree. Celis himself led a second expedition to establish a presidio, but met resistance from Páez's supporters and was unable to do so. Horcasitas removed him from command and placed Captain Manuel Muñoz in charge.

Muñoz completed the presidio in 1760 and called it Real Presidio de Nuestra Señora de Bethlen y Santiago de las Amarillas de la Junta de los Ríos Conchos y del Norte. The presidio's name was later shortened and known by various names including Presidio de Belén, Presidio de la Junta de los Ríos or Presidio del Norte. It was built near the pueblo of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, probably within the present-day town of Ojinaga, Chihuahua

The Presidio del Norte was immediately plagued with problems. A fiesta was planned to celebrate its completion and over 800 native people camped at La Junta in anticipation of the festivities. Many were Apache who claimed to be interested in peaceful relations with the Spanish. Instead, the Apache attacked the presidio at sunrise on the day of the dedication. One year later, half of the native people of La Junta had fled the area due to the tyrannies of the Spanish political and military officials. Father Lezaun wrote that:

...the Indians are much disturbed; and not the least cause of their exasperation is the damage that their crops and their sheep, cattle, mules and horses suffer at the hands of the captain and soldiers of the presidio.

Another La Junta missionary lamented that the Indians:

...indulged in their vices, dances, estufas, superstitions, witchcrafts, and idolatries in the mountains, while we [the priests] receive no favor, but on the contrary are interfered with when we try to compel the vicious and rebellious to receive their instruction and catechism. On the one hand they [the soldiers] give them protection in their disobedience to us, and on the other they harass and oppress them.

Most villagers apparently moved southwest up the Conchos where it was safer and where they could find work tending Spanish farms. Two years after the founding of the presidio, Muñoz and his men had not received any wages and were forced to petition Horcasitas for them. All the while, raids by the Apache and Comanche continued.

In 1767, the presidio was moved 30 miles up the Conchos to the pueblo of Julimes. After inspecting the northern frontier of New Spain the following year, the Marques de Rubí recommended that the presidio be returned to La Junta. In 1772, the king of Spain issued an order to reestablish Presidio del Norte. The following year, Colonel Hugo O'Connor, the newly appointed commandant inspector of presidios, carried out the king's order and reestablished the presidio at La Junta, where it remained until 1835.

Several changes came to La Junta with the establishment of the Presidio del Norte. In spite of the presidio's intended purpose of protecting and fostering missionary activity at La Junta, the increased secularization of the Spanish authorities of the time led to a gradual disintegration of the mission communities. Though the presidio could not stop the Apache and Comanche raids, it did finally put an end to the raids by Spanish slavers, who had plagued the people of La Junta for 200 years.

The same year (1773) that the presidio was moved back to La Junta, presidios were established at San Carlos and San Vicente, in the heart of the Big Bend on the Mexican side of the river. Collectively, the Spanish presidios along the Rio Grande created a string of forts that provided protection from Indian raids for Spanish settlers who were moving farther north and northeast onto the frontier. The return of soldiers to La Junta also marked the intensification of the practice of intermarriage between the Spanish and local native people, a pattern that continued throughout the Spanish period.

In 1779, Commandant-General Teodoro de Croix offered a truce to the Apache at the presidios of the northern frontier. He sent Muñoz to conclude a formal agreement with a group of Mescaleros who offered to serve as military auxiliaries on campaigns against hostile Gila Apache in return for food and protection. This agreement lasted until 1783, when most of the Mescaleros fled La Junta after a smallpox epidemic and a flood that destroyed their cornfields. Apache groups remained the biggest problem for the Spanish through their remaining years in the region. In 1785, Domingo Cabello, Governor of Nueva Vizcaya, negotiated an agreement with three Comanche leaders to wage war against the Apache in exchange for annual gifts and the cessation of hostilities towards them by Spanish forces. This agreement stayed in effect until Mexican independence in 1821, but did little to stop Apache raids on Spanish settlements.

Later in 1785, Benardo de Galvez became viceroy and developed a plan to coax Mescalero Apache peoples who feared attack from the Comanche into peaceful settlement on the northern frontier. Galvez died the following year, but his plan was approved posthumously by the king of Spain and implemented by Commandant General Jacobo Ugarte y Loyola. Mescaleros once again settled in La Junta on the condition that they farm and raise livestock, rather than rely on Spanish rations. They were initially issued weekly rations and these soon became a permanent fixture of the agreement. They were also allowed to leave La Junta to hunt game and gather wild plants to supplement their diet.

So many Mescalero took advantage of the Ugarte agreement that the Spanish could not feed them all and allowed some to move their encampments to the surrounding mountains so that they could sustain themselves on wild resources. Some of these Mescalero strayed out of Ugarte's jurisdiction into the territory of the neighboring commandant-general, Colonel Juan de Ugalde. Ugalde was unsympathetic to the truce and attacked the peaceful Mescaleros. He then refused to return his captives to their families, forcing the Mescalero to the brink of revolt.

In 1788, the new viceroy, Manuel Antonio Flores, became alarmed by continued reports of Apache hostilities on the frontier and ordered Ugarte to yield all of his power to Ugalde and all of the Apache at La Junta to be removed, ending the second effort to establish peaceful Apache at La Junta. Conde de Revillagigedo succeeded Flores as viceroy in 1790. He removed Ugalde and reinstated Ugarte, then authorized the resumption of peace negotiations with the Mescaleros, who settled once again at La Junta. Though they would not farm, they did serve as military auxiliaries to the Spanish. Many of them accepted Christianity and became part of the ethnically mixed population of La Junta.

Over the next few decades La Junta remained a remote Spanish frontier outpost, its presidio no longer staffed, its missions neglected. Its true native peoples were absorbed into the mestizo world of emergent Mexico. The main settlement at La Junta remained known as Presidio del Norte. |

Artist's depiction of a pitched battle between Spanish horsemen and the native peoples of La Junta. While the painting is somewhat fanciful, the La Junta native groups were raided many times by Spanish slavers seeking laborers to work in silver mines and agricultural fields located some 200 miles to the south. In response to continued raids, the people of La Junta revolted several times in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. At times this forced the small contingent of Spanish missionaries to retreat to the south to Parral. This 1994 painting by artist Feather Radha can be seen in Restaurante Lobby's OK in Ojinaga, Mexico. Courtesy Elsa Socorro Arroyo.  |

Northern New Spain showing key Spanish settlements and geographic features that figure in 18th-century history of La Junta. Also shown is the location of Casas Grandes, the Mexican town that formed near the major prehistoric center known by the same name.  |

Mexican majolica pottery dating to the 18th and 19th centuries found on the surface of the Millington site. Photo by Andy Cloud, CBBS.  |

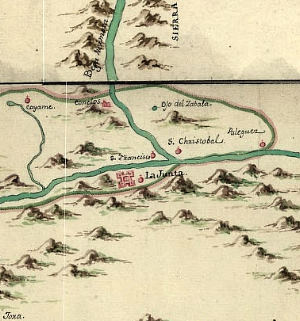

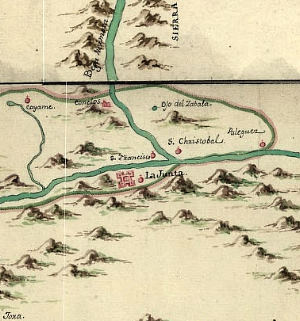

1769 map by José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez, a Mexican-born cleric and leading scientist educated at the best academies of New Spain. He created maps from records kept in the archives of Mexico, explorers' descriptions, and other maps of the day. This map depicts and labels the "Junta de los Rios del Norte y Conchos" fairly accurately for the day. The Rio de Conchos is shown as a smaller tributary of the Rio del Norte (Rio Grande), when in fact the Conchos contributed most of the combined flow of the two rivers. In the upper left is El Paso (del Norte) and in the lower left is Parral Real, the capital of the province of Nueva Vizcaya.  |

The village or ejido of El Mezquite still occupies the same gravel terrace (or pediment remnant) it did when the Spanish first visited and named it in the late 17th century. This community is located about 15 miles west of Ojinaga, to the south of the Río Conchos. Photo by Steve Black.  |

Urrutia's map of 1769 depicts the political and, to a somewhat lesser extent, the physiographic geography of northern New Spain in far more detail than any other mid-18th century map. Enlarge to see more of the map and learn more about its history. Map source: American Memory collection, Library of Congress.  |

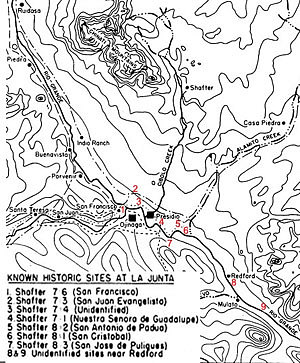

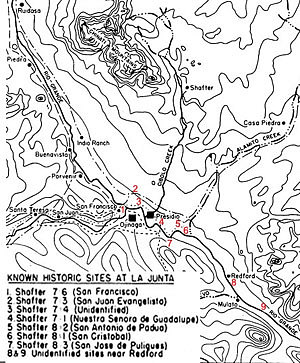

Location of known Spanish Colonial sites in La Junta area as well as the approximate routes taken by select Spanish entradas from 1581-1748. The Presidio del Norte is believed to have been located within (and under) the modern Mexican town of Ojinaga. Adapted from Kelley and Kelly 1990, Figure 1.  |

Maltese cross design on a large red-on-brown La Junta-style wide-mouthed olla found along Bear Creek in eastern Brewster County well over 100 miles east of La Junta. The design shows the influence of Spanish missionaries on La Junta peoples. This vessel was documented by Art Tawater, Archeological Steward for the Texas Historical Commission and partially reconstructed by Tawater and Ellen Kelley. Photo by Richard Walter. CBBS Collections.  |

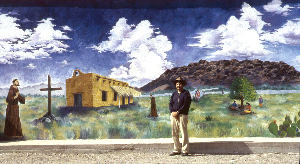

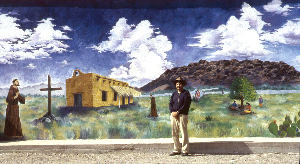

Enrique Madrid stands in front of a mural painted on a building in Presidio, Texas that is said to depict Mission de San Antonio de los Puliques, one of early, short-lived Spanish missions built along the Rio Grande near today's Redford, Texas. However, in the background is the distinctive Sierra de la Santa Cruz just southeast of Ojinaga, suggesting the mission shown is the one built at San Cristobal (the Millington site) within today's Presidio. Call it "artistic licence." The rather fanciful scene shows continued local identity with the area's Spanish Colonial heritage. Texas Historical Commission Archives.  |

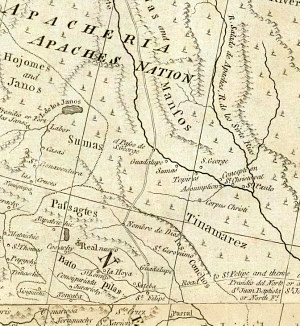

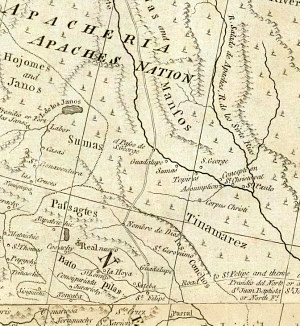

This 1776 map by British cartographer and publisher Thomas Jefferys reflects the inevitable geographic knowledge and publishing time lag of the day. Much of what the British knew about New Spain came from maps, charts, and sketches captured from Spanish warships as well as from published French maps. The string of named pueblos shown in the La Junta area appears to be taken from Delise's 1708 map. Note, however, the depiction of the Apacheria not far to the north. The large size of the lettering reflects the growing threat of the mounted raiders to the northern frontier of New Spain. Map source: David Rumsey Collection.  |

These copper and brass artifacts found on the surface of the Millington site probably date from Spanish Colonial times when the site was known as San Cristobal. Photo by Andy Cloud, CBBS.  |

|