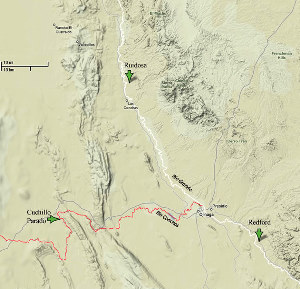

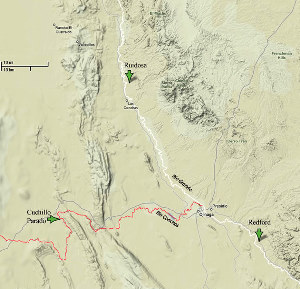

La Junta is a three-pronged oasis—well-watered green-lined ribbons amid the vast parched and rugged landscape of the northern Chihuahuan Desert. The oasis is formed by the lower Río Conchos and that stretch of the Rio Grande up and downstream from the two rivers' confluence. From the river junction, the La Junta settlement zone or district extends westward some 50 kilometers (31 miles) upstream along the Río Conchos to near the town of Cuchillo Parado in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. To the northwest it stretches some 55 kilometers (35 miles) upstream along the Rio Grande to near Ruidosa, Texas. And, to the southwest it extends some 35 kilometers (22 miles) downstream along the combined rivers to just beyond Redford, Texas.

The La Junta area is part of the larger Conchos Basin region of Mexico and lies at the southwestern edge of the Trans-Pecos region of Texas. Physiographically, the area is transitional between the central plateau of northern Mexico and the mountain and basin region of the southern Rocky Mountains. In geological terms, the region is typified by southeast/northwest-trending fault-block mountain ranges separated by extensive sediment-filled basins known as bolsons. Most of La Junta is located within the Presidio and Redford Bolsons at an elevation of about 2600 feet (800 meters) above sea level, which is significantly lower than the surrounding plains and mountains. The bolsons are ringed by mountains—from north to south on the eastern (U.S.) side of the Rio Grande these include the Sierra Vieja, and the Chinati and Bofecillos Mountains. From north to south on the opposite (Mexican) side of the Rio Grande these include the Sierras (mountains) de Ventana, Pinosa, de la Parra and Grande.

The Río Conchos is by far the mightier of the two La Junta rivers except during certain floods. The natural flow of the Rio Grande increases three-fold after it is joined by the Conchos. The Río Conchos flows permanently, while the Rio Grande often ceases to flow during prolonged droughts. This circumstance explains why all of the major historic pueblos (villages) of La Junta were located either on the Río Conchos or on the Rio Grande at or below the confluence. The Río Conchos and Rio Grande meander through alluvial floodplains that average 1.5 kilometers (just less than a mile) in width. Historicallly, the rivers frequently changed their courses, especially the Rio Grande. But today modern channelization, and drastically reduced flows caused by upstream dams and heavy agricultural use, have sharply reduced the meanders.

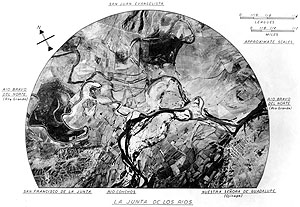

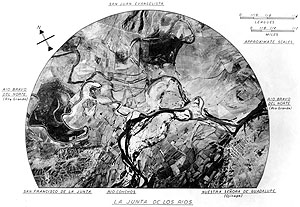

Aerial photographs reveal numerous abandoned (relict) channels strewn across the Rio Grande valley. In the past these relict channels often became curving marshes separated by sand and gravel bars left behind by floods. These low sandy hummocks were used by native peoples for farming because they were "sub-irrigated," meaning that high water tables kept the soil moist, at least between droughts. Naturally, such low-lying agricultural plots were also at the mercy of floods.

In addition to the Río Conchos and Rio Grande, La Junta is watered by the small, but perennial Alamito Creek and the ephemeral Cibolo and Tapado Creeks on the U.S. side and Arroyo de Valle Nuevo on the Mexican side. There are various other smaller creeks and arroyos that flow during heavy rains.

Adjoining the floodplain (T0 in geomorphological lingo) and rising some 6 meters (20 feet) above it is a low gravelly terrace (T1), varying in width from a few meters to two kilometers. It has a relatively level surface that is badly dissected by erosion. Modern-day Presidio and some of the historic pueblos were on this terrace. The main valley of the rivers is bounded by the steep slopes of a high gravel terrace (T2), which rises abruptly about 18-20 meters (60-65 feet) above the low terrace. In many places the "gravel terrace" is technically an alluvial fan of old river-borne materials redeposited by streams draining from the mountains. The surface of this terrace and abutting alluvial fans rises in steps toward the mountains, changing from a true alluvial terrace to a mountain pediment (a broad erosional surface at the base of a receding mountain). Small tributary streams have cut narrow valleys floored with the low gravel terrace that sometimes extend for kilometers into the high terrace, leaving long narrow finger-like mesas that are often isolated from the main terrace mass. The high flat-topped gravel mesas that extended directly to the floodplains near the rivers were the preferred location for historic pueblos. These locales spared the villages from all but the worst floods and provided ready access to the fields and waters below. Modern-day Ojinaga lies on just such a mesa.

La Junta is situated in the climatic and ecological realm of the Chihuahuan Desert. Its average yearly precipitation is only 21 centimeters (8 inches) and most of this falls in high-intensity downpours in the summer and early fall. The average annual temperature at La Junta is 70 degrees Fahrenheit, with the hottest temperatures in June and the coldest in January. The average summer temperature is 86 degrees Fahrenheit, and the daily highs frequently top 100 degrees. The average winter temperature is 51 degrees, and nightly lows seldom dip below freezing. The average difference in temperature between daily highs and lows for all months is 30 degrees or more, one of the largest average differences in the world. This remarkable day-night (diurnal) variation occurs because the La Junta skies are generally cloudless and humidity is low year-round, ranging from five to 45 percent, far lower than most of Texas. This makes the perceived temperature even lower than the actual temperature in summer and higher in winter. The sheltering mountains that surround La Junta buffer it from the cold winter winds that sweep across the surrounding plains.

La Junta was a very attractive place to live for desert-dwelling native peoples. The naturally irrigated low-lying floodplain proved ideal for farming by simple methods, except during severe droughts. Both the low and high terraces are relatively stone-free beneath the protective gravel surfaces with deep, fine-grained alluvial sediments. The fine sandy loam made it easy for the people of La Junta to excavate pits for houses, storage and burial. The gravel bars of the river and the mountain outwashes yielded diverse stones for making chipped-stone and ground-stone tools as well as cooking stones used in individual hearths and large roasting pits.

La Junta's unique setting at the juncture of desert, mountain and riverine environments, creates a diverse plant assemblage. The harsh climate of the Chihuahuan Desert limits the plants of the gravel terraces to those that are able to sustain themselves during long periods of high temperatures, short periods of below freezing temperatures and year-round dryness. Plants found here include ocotillo, creosote bush, lechuguilla, sotol, yucca, catclaw acacia, purslane, saltbush, sacaton, pigweed, goosefoot, guayacan, leatherstem, allthorn, tarbush, huisache, palo verde, chino grams, mormon tea and numerous species of cacti. Before the advent of historic ranching and overgrazing in the region, the short grasses on the gravel terraces were much more prevalent than is the case today. The mountains are able to support more temperate species, such as piñon and juniper. The well-watered floodplains support riparian species, such as willow, cane, and cottonwood. The river marshes supported still other species such as cattail.

La Juntans exploited most of these plants for many different purposes, from food to tool making to house construction to medicine and ritual. Among the food plants were yucca, agave, sotol, mesquite, prickly pear, purslane, saltbush, sacaton, pigweed and goosefoot. In addition to gathering wild plants, they sometimes grew domesticated species, such as corn, beans, gourds, and squash, as well as species introduced by the Spanish in later times. The people of La Junta used the wood of willow, mesquite and cottonwood and the stalks of ocotillo, yucca, lechuguilla and sotol in the construction of dwellings and windbreaks. They also used the wood of mesquite, and to a lesser extent, tarbush, huisache, palo verde, cottonwood, and willow for fuel in fires and the leaves of yucca, lechuguilla and sotol for making baskets, cordage and sandals. The species mentioned here undoubtedly represent only a fraction of the true range of plants used by the native peoples—few detailed botanical studies have yet been carried out from samples collected at village sites.

The fauna of La Junta is equally as varied as its flora. Among the animals of the desert and mountains are several species of deer, antelope, black bears, skunks, porcupines, rabbits, pocket gophers, prairie dogs, rats, squirrels, foxes, wolves, coyotes, badgers, bobcats, raccoons, ringtail cats, mountain lions, javelina, doves, quail, hawks, eagles, roadrunners, carrion birds and song birds. The rivers and surrounding riparian zone are home to muskrats, beavers, migratory birds, turtles, frogs, snakes, catfish and mussels. The people of La Junta exploited most or all of these animals and others for their meat, bones, sinew, hides, feathers, and shells. Once again, few detailed faunal studies have yet been done.

All in all, La Junta was truly a desert oasis for the native peoples of the Chihuahuan Desert, a three-pronged river basin providing diverse resources - water, plants, animals, stones, and soil - that has attracted and sustained humans for at least several thousand years, and probably much longer. |

The three-pronged La Junta settlement zone or district extends westward some 50 kilometers (31 miles) upstream along the Río Conchos to near the town of Cuchillo Parado in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. To the northwest it stretches some 55 kilometers (35 miles) upstream along the Rio Grande to near Ruidosa, Texas. And, to the southwest it extends some 35 kilometers (22 miles) downstream along the combined rivers to just beyond Redford, Texas. Base map, Google Maps, terrain view.

|

Aerial photograph of La Junta, the confluence of the Rio Bravo del Norte (Rio Grande) and the Río Conchos showing relative locations of three of the major pueblos as they were known to the Spanish in the colonial era. This graphic was created by J. Charles Kelley using an aerial photograph probably taken in the 1940s. It shows the area before most modern agricultural and urban development, hence many of the abandoned former channels of both rivers can still be traced. This complex web of old channels, floodplains, and low marshy areas, explains why productive agriculture was possible at La Junta beginning by around 800 years ago. Center for Big Bend Studies Archive, Sul Ross State University.  |

The actual confluence or "junta de los rios" as it appeared in 1973 prior to channelization. In the foreground the Rio Grande flows right to left toward the right-center of the photo, where the Río Conchos joins, also flowing right to left. In other words, the photographer was looking downstream at the confluence from just above it while standing on a gravel bar of the Rio Grande. Historically, considerably more water flows from the Río Conchos and the wide area is pooling water that backs up from the confluence. TARL Archives.  |

View looking northeast across the Presidio Bolson from a gravel-topped high terrace on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. In the background the cities of Ojinaga (on the left) and Presido can be seen. Five hundred years ago, several small pueblos would have been visible along the rivers. Photo by Andy Cloud.  |

Low-angled early morning aerial view of La Junta, looking southeast. Ojinaga, Mexico stretches across photo. In the foreground is the Rio Grande just upstream from the confluence. 1983 photo by Bob Parvin, courtesy Texas Historical Commission.  |

Aerial photograph taking in the 1940s showing the Polvo site's setting in the Rio Grande valley. The site lies within the red circle on a high terrace overlooking the river. Just across the river in Mexico a wide band of gravel marks the dry streambed of a major tributary creek, Arroyo de Valle Nuevo (locally known as Arroyo de la Mula and Arroyo del Cañoucito). Most of its normal flow today is captured by dams and agricultural pumping upstream. In earlier times the arroyo would have been a more dependable source of water. The farmed areas are river floodplains (low terraces) with deep alluvial sediments. From Shackelford 1951.  |

The Rio Grande valley below and above the La Junta district is confined within narrow canyons and unsuited for agriculture, ancient or modern. Photo by Andy Cloud.  |

View south looking across the Rio Grande valley from the Millington site, which occupies a gravel terrace overlooking the lower active floodplain used for agriculture today as it was (on a much smaller scale) when the Spanish arrived. In this late winter photo, the river appears as a curving brown line of trees and cane. The green plants in the foreground are mesquites and creosote bushes on the site. Texas Historical Commission Archives.  |

|