First Villagers

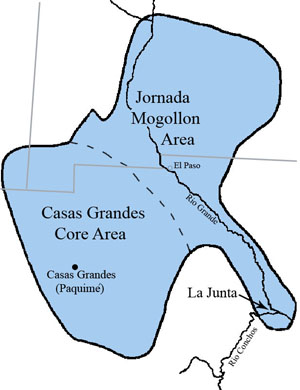

Kelley thought the first La Junta villagers were colonists from the El Paso area where Jornada Mogollon peoples had been living in settled villages and practicing agriculture for centuries. Early village life in La Junta was also influenced by the Casas Grandes culture, as evidenced by imported pottery and shell ornaments. Kelley suggested that La Junta may have supplied agave/sotol cakes, bison hides, and other resources to Casas Grandes. |

|

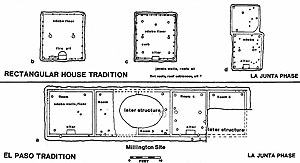

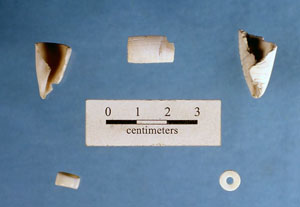

About 800 years ago (A.D. 1200), if not earlier, settled life began at La Junta de los Rios with the establishment of villages on gravel terraces overlooking wide expanses of the active floodplains along the two rivers. The villagers tended fields on the floodplains where they raised corn, beans, gourds, and squash, but they did not live off crops alone. They also gathered wild plants, hunted wild animals, and netted fish. They lived in semi-subterranean rectangular houses with upper walls and flat roofs that protruded above ground. They were part of a vast social and economic network spread across northwestern Coahuila, southern New Mexico and far western Texas. Archeologists call this network the "Casas Grandes interaction sphere" because the prehispanic city of Casas Grandes or Paquimé was the dominant center of power, population, and cultural sophistication between A.D. 1200-1450. Paquimé has been characterized as a redistribution center, the central node of a wide trade and exchange network that connected diverse cultures and places. La Junta lies at the eastern edge of the Casas Grandes interaction sphere, being situated some 200 miles east-southeast of the great center. The connection is most easily recognized by the presence of numerous types of Casas Grandes pottery at La Junta. The pottery, as well as easy-to-trace durable "exotic" goods such as ornaments made of shells found in the Gulf of California and, doubtlessly, many rarely preserved perishable items such as foodstuffs, hides, baskets, crop seeds, and textiles, moved through an extensive trade network that connected the seemingly remote villagers with the distant redistribution center. We aren't really sure what the La Junta villagers provided, but Kelley thought that sugary cakes of baked desert succulents and animal hides were among the likely candidates. The identity and origins of the first La Junta phase villagers are debated. Kelley thought they may have been colonists from the Jornada Mogollon area in what is today the southeastern part of New Mexico, the western Trans-Pecos Mountains and Basins and the northeastern part of the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Jornada Mogollon pithouse villages were first established some 1600 years ago (A.D. 400) as agriculture, pottery making, and settled life spread across most of the greater American Southwest. But according to Kelley it was not until around 800 years ago that these changes came to the La Junta district. Similarities in early architecture and the relative abundance of a Jornada Mogollon pottery type called El Paso Polychrome, argue in favor of the idea that the first villagers were colonists that came from the northwest following the Rio Grande. Alternatively, Robert J. Mallouf has suggested that the first villagers may have been hunting and gathering peoples native to the Chihuahuan Desert who were strongly influenced by the Jornada Mogollon and Casas Grandes cultures. In this scenario, certain native groups adopted a new lifestyle emulating their more sophisticated distant neighbors, doubtlessly after becoming allies and growing familiar with settled life. The "extensive trade network" would have also been a social network through which ideas and knowledge of other societies spread. Evidence in support of this "indigenous development" model includes the fact that while there are architectural parallels, the La Junta pithouses have somewhat different construction methods. Also, while most of the pottery seems to have been made elsewhere, most of the stone tools and other artifacts used by the La Junta villagers are made of local materials in the same styles as the hunting and gathering peoples of the eastern Trans-Pecos. Another reason to cast doubt on the idea that the first La Junta villagers were Jornada Mogollon colonists who arrived around A.D. 1200 is because some researchers suspect that village life at La Junta may have begun earlier, perhaps even hundreds of years earlier. This speculative guess is based on the fact that we now know that pithouse villages, agriculture, and pottery making began hundreds of years earlier elsewhere across the American Southwest including the western Trans Pecos and in the Casas Grandes area. It would not surprise many current researchers in the region to learn that La Junta shared in these early developments. If so, archeologists have yet to find convincing evidence of this, but then again, we have only recently begun to look for it. Regardless of how or when it began, village life was firmly established in the La Junta district by 800 years ago and it flourished for some two and half centuries during what archeologists call the La Junta phase (A.D. 1200-1450). Village life at La Junta continued for hundreds of years beyond that, but many things changed with the intrusion of the Spanish in the 16th and 17th centuries. As explained in Investigations and Sites, J. Charles Kelley began to explore the La Junta villages in 1936. Over the next thirteen years he and his colleagues and students excavated several dozen houses and other features at five sites, most dating to the La Junta phase. Three types of houses were identified among the relatively large sample of documented houses: rectangular pithouses, circular pithouses and a single example of a multi-roomed pueblo. The unique multi-roomed pueblo uncovered at the Millington site consisted of a tier of five rooms arranged in an east-west direction and built within a shallow pit about 18 inches (45 centimeters) deep. Kelley suspected that the pueblo was the earliest structure built at the site and noted that it "is virtually identical to the smaller Jornada branch pueblos of the El Paso area." The walls were made of adobe (dried mud) reinforced with upright poles and built directly upon an adobe floor. The adobe was "puddled," meaning that it was applied in layers rather than as stacked bricks. Adobe was also used to construct low "curbs" that divided the rooms as well as large rectangular blocks that were set against the south walls of at least two of the rooms. These blocks have been interpreted as ritual altars due to the apparent lack of use wear, their regular occurrence along the south walls of other structures, and architectural parallels elsewhere. In contrast, most La Junta phase houses were rectangular pithouses that stood apart from one another. These modest-sized structures range from about 100 to 225 square feet (10-21 square meters) in floor area. The semi-subterranean houses were built within pits that ranged from one to six feet deep. The upper walls and roofs of the La Junta pithouses protruded above ground level. The walls and roofs of all but one of the excavated houses appeared to have been constructed using the jacal technique. The walls were formed of closely spaced upright wooden poles (ocotillo stalks or small saplings) woven together with thin branches and then plastered over with adobe. The roofs had more substantial rafters over which layers of woven poles, thatch and mud were placed. The floors were of puddled adobe or tramped gravel and occasionally had low adobe curbs around the walls. The superstructures (walls and roofs) were supported by a combination of large and smaller interior posts that were set into the pithouse floors. Most rectangular pithouses stood apart from one another, aside from a single pair with adjoining walls. These probably represent an original house to which a second room was later added. A most unusual and larger than average rectangular pithouse was excavated at the Polvo site. Instead of puddled adobe construction, its walls were made of turtle-back shaped, hand-made adobe bricks that began at the ground surface (instead of being built up from the pit floor). Another unique feature of this house was the occurrence of smooth plastered interior walls with designs painted in yellow, black, red, and white colors. This pithouse could represent a religious or communal structure analogous to a Southwestern kiva. The circular to oval pithouses were very small, with diameters of less than three meters (10 feet). They had tramped gravel floors and framework posts arranged around the periphery of the floor. It appears they were built over the pit, with pole walls starting at ground level. These may represent granaries such as those mentioned by early Spanish chroniclers. Another common feature in La Junta villages are "ring middens" or baking pits in which semi-succulent desert plants such as agave and sotol were processed. Kelley suggested that these baked plant foods (probably in the form of dried sugary cakes) may have been one of the commodities that the villagers sent to Casas Grandes. The La Junta phase villagers seem to have imported most of their pottery from source areas at least 150 miles to the west and northwest. These Southwestern trade wares consistently include El Paso (Jornada Mogollon) and Chihuahua (Casas Grandes) polychromes. Of these, El Paso Polychrome is the most common. The most common Chihuahua polychrome types include Ramos, Babicora, and Villa Ahumada. Other trade wares included Tusayan Polychrome, Playas Red, and Chupadero Black-on-White. Recent chemical and petrographic analyses of El Paso Polychrome sherds from the Millington site confirm that the pottery was made in the El Paso area. Unlike the imported ceramics, La Junta phase arrow points suggest a strong relationship with hunter-gatherers in the surrounding region. The most common styles are what Kelley called Piedras Triple Notched, Perdiz Stemmed, and Fresno Triangular, all types uncommon or nonexistent in the El Paso phase assemblages but regularly seen in hunter-gatherer settings across the Big Bend. Modern researchers have lumped the Piedras Triple Notched and the Toyah Triple Notched (which Kelley associated with the Livermore phase) types into a single type termed "Toyah," despite protests by Kelley. Perdiz Stemmed and Fresno Triangular are simply known as Perdiz and Fresno points today. A distinctive type of artifact associated with the La Junta phase, and later Bravo Valley phases as well, are notched pebbles thought to represent "sinkers" or net weights used for fishing. These smooth river pebbles have percussion notches at opposing ends (or sides), some struck bifacially and some unifacially. Although their inferred function as fishing net weights, as first suggested by E. B. Sayles in 1935, has yet to be definitively demonstrated, the fact that they occur only at sites along the Rio Grande and the Río Conchos supports the idea. Interestingly, notched pebbles also occur in the contemporary Cielo complex sites located on high terrain within the Rio Grande valley, but do not seem to occur at the many Cielo sites found outside the river valley. Kelley thought that the La Junta villages were abandoned around A.D. 1450, probably because prolonged drought conditions made farming too unpredictable. He suggested that there was a decades-long hiatus or break in continuity between the first villagers and those who were responsible for the Concepcion phase during the early Spanish Colonial era. Convincing archeological evidence of this hypothesized hiatus has yet to be set forth. We think it more likely that, while village life would have been disrupted by repeated crop failures, the La Junta villages were not totally abandoned. There probably were periods lasting many years and perhaps decades during which drought conditions prevailed and made agriculture impractical. But we doubt that the established populations simply picked up and left. Hunting and gathering always provided important contributions to the villagers' food supplies and would have become essential mainstay strategies during droughts. Prolonged dry periods would have also forced more mobility and kept people from staying in the villages year round. As Mallouf has suggested, the villagers may have simply "reverted to a largely hunting and gathering lifeway" shared by the contemporary and nearby peoples of the Cielo complex. The conflicting interpretive models of early village life are further evaluated in La Junta Reconsidered. While we know of the first villagers only from archeological evidence, the Spanish appeared on the scene in the sixteenth century and the era of written history began. |

|