La Junta Sites

|

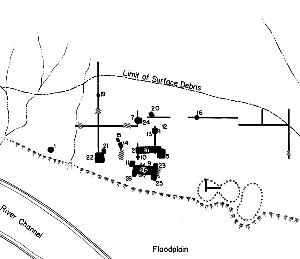

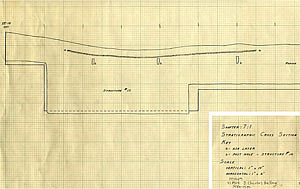

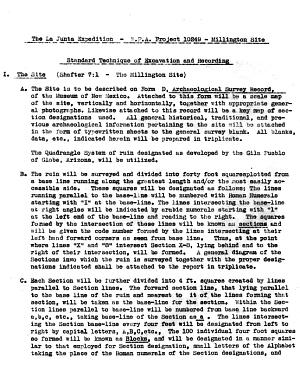

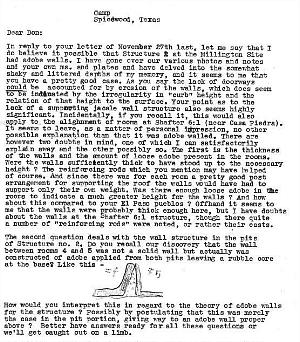

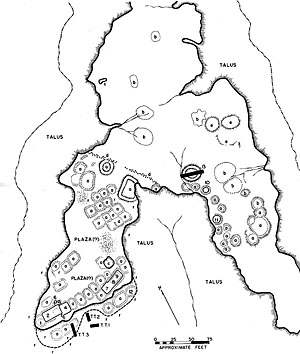

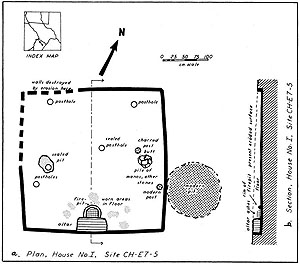

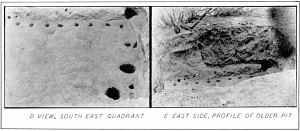

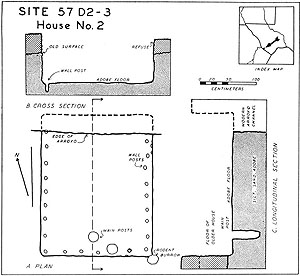

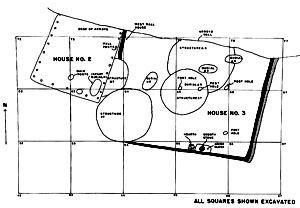

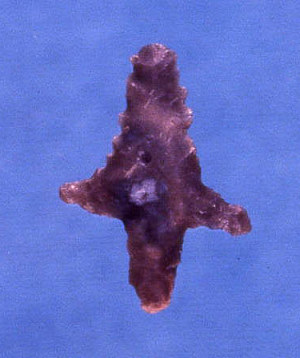

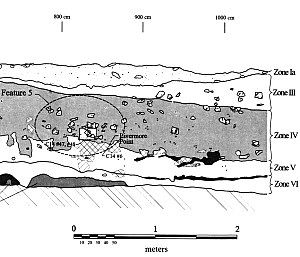

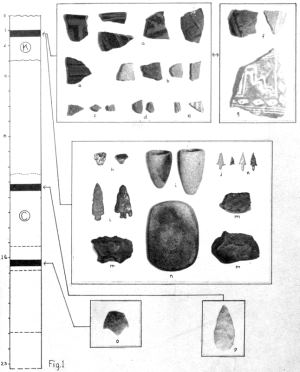

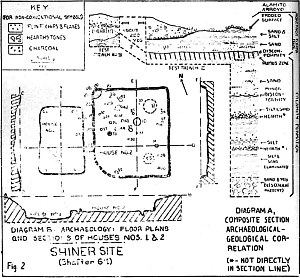

Archeologically, the La Juntan culture is primarily known from excavations at six sites, all but one of which are located in the United States. As detailed in Investigations, most were carried out under the direction of J. Charles Kelley in the late 1930s and late 1940s at three sites, Millington, Loma Alta, and Polvo. Kelley and his colleagues and students uncovered pithouses and other architectural features at these sites (and several others) and worked out a chronological sequence tracing the development of the Bravo Valley culture from its beginnings around A.D. 1200 through Spanish colonial times. In the 1990s, a new era of La Junta site investigations began, led by author Andy Cloud and Robert J. Mallouf at Millington, Polvo, and Arroyo de la Presa. This work has begun to provide the modern scientific data that is needed to evaluate and refine Kelley's many stimulating ideas and hypotheses. Unfortunately, the archeological work done over 50 years ago was never completely reported or synthesized, most critically the work done at Millington and Loma Alta, the two sites that were investigated most thoroughly. Fortunately, Kelley did publish numerous articles on his work as well as his dissertation and several useful summaries written in the 1980s that contain previously unpublished illustrations prepared decades earlier. There is also the fact that archeological work in the 1930s and 1940s was done in a quite different fashion from the methods used in recent decades, a statement that holds true of most work done all across North America. On the positive side, archeologists of the period excavated much more quickly, allowing the exposure of broad areas, a particular advantage in the case of large architectural features such as pithouses. But the downside was often meager documentation, sampling, and analysis. Instead of crews of trained archeologists, one or two archeologists typically led teams of laborers. The archeologists of the day did the best they could within the constraints of prevailing methods, limited funding and time, and relatively primitive analytical methods. (Radiocarbon dating, for instance, was then only in the process of being developed.) Here we review each of the La Junta sites that has seen excavation and summarize what was learned. The results of recent work are summarized in more detail to highlight the research potential of (and need for) more modern investigations. MillingtonThe Millington site (41PS14) is a large prehistoric to early historic village located at the southeastern edge of Presidio, Texas. It extends several hundred meters along the upper edge of the first terrace above the floodplain of the Rio Grande. It was likely the village identified as "Santiago" during the Espejo entrada (official expedition) of A.D. 1582-1583, and was said to be the largest settlement the group visited at La Junta. A Spanish mission was apparently established there, probably in A.D. 1684 by the Mendoza-López expedition. The site was also visited by several eighteenth-century entradas—Trasvina y Retis (A.D. 1715), Ydoaiga (A.D. 1747-1748), Rábago y Therán (A.D. 1746-1747), and Tamerón y Romeràl (A.D. 1765)—all of which referred to the site as "San Cristóbal." Indian groups said to reside at the site during two of the visits were the "Patarabueyes" (Espejo) and the "Síbolos" (Ydoiaga). The Millington site was originally brought to the attention of J. Charles Kelley in June 1937 by V. J. Shiner, a local artifact hunter who lived in Presidio. Shiner had excavated a pit roughly 1.5 meters in diameter into the deposits of the site. Kelley spotted an apparent house floor in the pit walls and subsequently expanded this excavation, uncovering the remnants of a circular pithouse. A flexed adult burial was discovered within a pit covered by a stone cairn that extended above the level of the floor. Major excavations were carried out at Millington from October 1938 through July 1939 by Kelley and a budding archeologist and undergraduate student, Donald J. Lehmer. Funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) program, the labor force consisted of unemployed men from Presidio and nearby communities, most of them Mexican-Americans. Kelley planned and oversaw these excavations. Lehmer was field director for most of the work, until Kelley took this role over for the final month or two. Work at the site was extensive and 21 additional houses were excavated; another nine were documented in hand-dug trench walls. Excavations were concentrated in the heart of the site, but were supplemented with testing in other areas. In the early 1940s Lehmer and Kelley worked on what was to be a major report on the Millington site. Unfortunately, the manuscript was never completed. This circumstance can probably be attributed to two factors. With the demise of the WPA program soon after World War II began many major archeological projects were never completed. (For instance, the WPA work at the Morhiss site in south Texas.) The 1940s were also key periods in the development of the young archeologists' careers. Both Kelley and Lehmer continued their educations in the early 1940s, both served in the Army during the later years of the War, and both earned doctorate degrees from Harvard University in the late 1940s. Lehmer went on to become a leading expert in Northern Plains archeology, while Kelley became best known for his work in the northern Mesoamerican frontier in north-central Mexico. The results of the Millington work did figure prominently in Kelley's dissertation and in interpretive articles he published on various aspects of La Junta archeology and ethnohistory. He identified occupations at Millington which he dated to the La Junta, Concepcion, and Conchos phases (which he called foci). In fact, Kelley considered the site to be a type site for the La Junta and Conchos phases. Rectangular and circular house traditions were associated with all three phases at the site, while a small adobe-walled pueblo with five contiguous rooms was linked to the La Junta phase. The latter structure was thought to be similar to early Jornada Mogollon pueblos around and north of El Paso. Kelley suggested it may have been the earliest structure excavated at Millington. Comparable structures have yet to be found at other La Junta sites. The Millington site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 as part of the La Junta Archeological District. The four-acre "heart" of the site became the property of the Texas Historical Commission (THC) in 1986 and was declared a State Archeological Landmark in 1987. At the time of the THC purchase, a fence was erected around the property and signs in both English and Spanish provided information about the site's importance to the archeology of the area and legal protections afforded it. Although city roads and a federally funded housing project impacted adjacent areas at that time, the state and federal designations and signage have helped to protect most of the site over the years. However, several human interments were accidentally uncovered in an adjacent roadway in 2003 during an attempt to refurbish an old water line. The Center for Big Bend Studies (CBBS) of Sul Ross State University, in consultation with the THC and City of Presidio, documented the disturbances at that time, returning to the site in 2006 for more substantive work. With funding from the Texas Preservation Trust Fund (Texas Historical Commission), the City of Presidio, and the Trans-Pecos Archaeological Program (TAP) of the CBBS, the 2006 investigation concentrated on salvaging the burials exposed by the backhoe while exploring several other features also revealed by the disturbance. In addition, the site was mapped with a Total Data Station (TDS), an extensive controlled surface collection was made, and several areas of the site were explored through geophysical techniques (ground penetrating radar and conductivity) in an effort to identify buried features. Five human burials and portions of three structures were uncovered, providing new data on La Junta architecture, mortuary practices and health. One structure was in a pit some 60-80 centimeters deep that was partially obscured by later intrusions. Lacking a prepared floor, the structure contained several burned vertical posts, and burned roof fall. The roof fall included several layers of fibrous material (possibly grass), river cane, and probable willow shoots, as well as larger sticks or poles, crisscrossed materials, daub, and mud-dauber nests. Radiocarbon assay provided a La Junta phase date of A.D. 1290-1410. While the only partially exposed structure is probably a pithouse, it could also be a ramada (shade awning) attached to a house. A ramada was documented in one instance at Millington in the late 1930s. The second structural remnant uncovered in 2006 was a rock wall that spanned a distance of 1.6 meters across one unit. The 40 centimeter high wall was made principally of small vesicular basalt boulders, with fallen stones, charcoal, and charcoal-laden sediments on either side. A charcoal sample from its base yielded a date of A.D. 1730-1810, suggesting the wall was built during the middle to late Conchos phase, or perhaps a bit later. Although the limited excavations did not reveal what type of structure the wall represents, this is the first stone-based construction documented at a La Junta site. The final structure uncovered in 2006 was a house constructed in a pit about 30 centimeters deep. It contained a previously unreported architectural element: an adobe backing (thin layer) on the original ground surface, adjacent to, and angled away from, the pit. This may be a rainwater deflector. The floor of the pithouse was hardened and appears to originally have been puddled adobe several centimeters thick. Its patchy, irregular surface and the lack of burned wall or roof fall suggest the superstructure was salvaged after abandonment and the floor subsequently eroded before the pit was filled. Found within a pit in the floor was a human interment covered with cobbles. A bone collagen date of A.D. 1160-1290 was obtained from the burial, effectively dating the structure to the early La Junta phase. Five human interments were excavated in 2006. These consist of an early adolescent, two adult males, one female, and one adult of indeterminate sex. Radiocarbon dates on bone collagen from three of the burials place them within the La Junta phase, with one date extending into the Concepcion phase. Three of the individuals were interred in individual pits outside any apparent structure, one in a midden, and one beneath the floor of the pithouse. All of the individuals were placed in a partially flexed or flexed position, supine or on the side, seemingly with no consistent orientation. None of these five burials was accompanied by mortuary goods. These La Junta phase burial characteristics are consistent with Kelley's earlier findings. Unusual features, found in two of the Millington burials, were upright stones used to define portions of the pit borders. These stones were associated with the western pit edges of Burials 1 and 2, containing an early adolescent and a 30 to 40-year-old male. All of the adults displayed joint degeneration, most severely expressed in the vertebrae and lower extremities. Stable isotope analysis on three adults indicates a mixed diet with an emphasis on C3 plants and terrestrial meat, limited consumption of desert succulents, and less than 25% contribution from maize. These results are surprising, given archeological and historical evidence for maize agriculture and desert succulent processing at Millington. Additional details and interpretations are presented in New Insights. Loma AltaLoma Alta (41PS15) is the archeological site thought to be the early historic pueblo of San Juan Evangelista. It is located on a pediment on the east bank of the Rio Grande about 5 miles above the modern town of Presidio, opposite the mouth of the Río Conchos. This village was occupied during the La Junta and Concepcion phases and is considered the type site of the latter phase. In fact, Loma Alta is the only La Junta site for which the basic Concepcion phase village layout is known. Kelley undertook excavations at Loma Alta in 1939, with support from the Work Progress Administration, the School of American Research, and E. B. Sayles of Gila Pueblo. Small-scale salvage excavations at Loma Alta were conducted in 1973 by Vance Holliday and James Ivey of the Texas Archeological Survey of the University of Texas at Austin. This work was very limited in scope and involved only the documentation and recovery of endangered portions of two burials that were exposed by erosion in a small arroyo. Apart from site visits by Kelley and archeologists from the Texas Historical Commission in the 1980s, no additional research has been carried out at Loma Alta. Kelley's work at Loma Alta included the excavation of rectangular pithouses with associated small circular structures. The earliest rectangular houses, constructed in pits and floored with adobe, are typical of the La Junta phase in the region and indicate the onset of occupation at the site. Most of the structures at Loma Alta are larger than the La Junta phase houses and lack adobe curbs or floors, dating them to the Concepcion phase. These houses were often built side by side in east-west rows, with nearby smaller circular structures suspected to be storage facilities (granaries). Kelley thought that the increase in residential house size seen at Loma Alta represented an important social change. Whereas the smaller La Junta phase structures probably housed single family units, he inferred that the larger Concepcion phase residences were used by extended families, and noted the occurrence of multiple hearths in each house. Kelley considered Loma Alta to be the best example of the Concepcion phase in the La Junta district, and found no evidence for later occupation at the site. Historical accounts concur with this interpretation, as San Juan Evangelista is mentioned by members of the Espejo entrada in 1582, and is absent from the accounts of subsequent entradas. The Espejo party describes the pueblo as rows of rectangular houses atop the pediment and "suburbs" along the slope. This description matches the archeological data and, combined with the location description, confirms that Loma Alta is San Juan Evangelista. Kelley postulated that the occupants of Loma Alta probably moved to the nearby site of Kopenbarger (Shafter 7:4 or 41PS16) at the outset of the Conchos phase, before the founding of Spanish missions in 1684. He tentatively identified the historic population of Loma Alta as the Conejo (Spanish for "rabbit") Indians, one of the primary native groups mentioned in late 17th century Spanish documents. Loma SecaLoma Seca (Chihuahua E7-5) is a La Junta phase site in northern Chihuahua discovered by Kelley during his 1949 survey of the Río Conchos drainage. This work was undertaken with support from the Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of Texas. The site lies approximately one kilometer south of the Río Conchos on a terrace at the foot of a high mesa, outside of the modern town of Ojinaga. It is the only La Junta site in Mexico that has seen any excavation. The site layout of this relatively small La Junta village was exposed by extensive sheet erosion. Kelley was able to discern rows of rectangular houses flanking a central plaza area running the length of the site. He recognized debris from collapsed and burned houses, and nearby middens. Kelley saw no evidence of occupation at Loma Seca later than the La Junta phase, and concluded that the site had been occupied for a relatively short period of time between A.D. 1200 and 1400. Taking advantage of the erosion, Kelley undertook the excavation of a burned pithouse that lay just under the surface. He found this nearly square structure to be typical of the La Junta phase. Postholes and burnt remnants on the adobe floor indicated that the walls and roof were constructed of jacal, overlaid by a thin covering of adobe. An altar against the southern wall of the house had a fire pit in front of it, features that he had documented at La Junta phase structures at Millington and Loma Alta. In a 1951 article on the site, Kelley used the Loma Seca house altar to argue that the consistent southern location of such features suggested that La Junta phase houses had been oriented on cardinal directions, rather than being aligned with respect to the river. PolvoThe Polvo site (41PS21) is a large village located along the banks of the Rio Grande outside the small community of Redford, Texas. Situated on a terrace about five meters above the river, the site occurs at the confluence of the Rio Grande and a small intermittent stream, Arroyo de la Iglesia (Church Creek). Directly opposite the site on the Mexican side a much larger tributary creek, Arroyo de Valle Nuevo, enters the river. This location was known in Spanish documents as the site of Tapacolmes. Archeological and ethnographic evidence suggests strongly that the Polvo site was also the location of an early Spanish mission, San Pedro de Alcántara de los Tapalcomes, established for the Pescados and Tapacolmes Indians in 1715. The site was apparently visited by both the Rábago y Therán and Ydoiaga entradas in A.D. 1747, who reported the former pueblo was abandoned and that "thick walls of what was a church or chapel of adobe" were in ruins. Sixty Pescado Indians living a short distance upstream at the village of San Antonio de los Púliques told the Ydoiaga party that they had abandoned Tapacolmes because of Apache raids. Kelley was first shown Polvo in 1938 by V. J. Shiner, and returned to the site ten years later during an archeological reconnaissance on the Texas side of the Rio Grande between Redford and Fabens. Fifty-eight sites were visited and recorded during the project which was conducted through a grant from the Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of Texas with sponsorship by the Department of Anthropology of that institution. The work also involved more intensive investigations of four sites, including the Polvo site where two structures exposed in an arroyo cut bank were partially excavated. Both structures Kelley excavated at Polvo were rectangular pithouses with prepared clay/adobe floors. The floor or base of the pit of the more intact house was 55 centimeters below the former ground surface and contained a series of postmolds around its exterior, indications that the jacal superstructure was anchored within the pit. Measuring approximately 2.2 x 2.5 meters, the structure contained on its floor a sherd of El Paso Polychrome, a flake side scraper, a pestle, two bone awls, an antler "tool handle," a gourd vessel fragment, a textile fragment, and a stone concretion. Based on the available evidence and other work in the district, Kelley estimated the house dated between about A.D. 1300-1400 or slightly later, and assigned it to the La Junta phase. In the summer of 1949 Kelley returned to the Polvo site as director for a University of Texas Anthropology field school, the first such college training program ever carried out in the Big Bend. Work was concentrated in the immediate area where Kelley had previously excavated. The group further exposed and documented one of the previously excavated houses (House 2). Adjacent to it, they uncovered a large, partially intact rectangular pithouse intruded by four circular pit structures and five burials. All of these features had in some way cut into at least one of the others, allowing a relative construction sequence to be understood. Graduate student William J. Shackelford analyzed and reported the 1949 work for his master's thesis. Shackelford's thesis on Polvo ranks as the most thorough documentation of any of the La Junta sites excavated in the 1930s and 1940s. The newly excavated structure, House 3, proved quite instructive as it contained several Southwestern architectural elements unseen at other La Junta sites. These unusual elements combined with the large size of House 3 and its complicated array of superimposed pits and burials, suggests that this was no ordinary dwelling. It may well represent a small communal structure analogous to a Southwestern kiva. This possibility was mentioned, but could not be confirmed because of the extensive intrusive pits and the destruction of the north side of the structure by the arroyo. A layer (8-13 centimeters thick) of adobe plaster lined the inside walls of the structure, which had an additional adobe molding plastered against the base of the inside wall. There were clear traces of four painted colors (yellow, black, red, and white) on the plaster lining the inside walls, although the overall design could not be discerned. Painted and plastered adobe walls have been documented at many Southwestern pueblos, but this is the only example known in the La Junta district. In the center of the south wall against the adobe molding was a raised adobe altar block with a polished stone slab embedded on its top. The house walls had been constructed of turtle-back shaped adobe "bricks," which started at ground level. This construction technique has not been seen at other La Junta sites, although similar walls had been reported from El Paso phase Jornada Mogollon sites in southern New Mexico. One of the pits contained the only adult (a female) burial recovered at the site; the other four burials were all of infants. Shackelford concluded that all of the features excavated during the field school were affiliated with the La Junta phase. Archeologists from the Texas Historical Commission (THC) revisited the site in the 1970s and 1980s and began trying to protect it. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and declared a State Archeological Landmark in 1983. Additional testing was carried out at the Polvo site in 1994 under the direction of Robert J. Mallouf, then the Texas State Archeologist for the THC. This work was done in response to inadvertent damages inflicted by the Soil Conservation Service during an emergency repair of the Presidio-Redford earthen floodwater retaining levee. Several areas of the site were investigated with hand-excavated units, cutbank profiles, and surface collections. Two probable pithouse remnants were observed and profiled in the cutbank along Arroyo de la Iglesia in the area where Kelley had previously worked, with one of these containing several house floors (one consisting of puddled adobe), a post mold, a sub-floor pit or additional large post mold, and probable burned roof debris overlying the floors. Radiocarbon samples from these sub-features yielded corrected and calibrated dates of A.D. 1308-1358, A.D. 1349-1389, A.D. 1305-1365, and A.D. 1252-1305, with the average of the midpoints falling around A.D. 1330, or roughly in the middle of the La Junta phase. A large refuse pit yielded a corrected and calibrated date of A.D. 1190-1280, which helps date a Toyah arrow point found within the pit. In another area of the site, a probable post mold was uncovered that may be associated with an early Spanish mission dating to the 1680s or early 1700s. Arroyo de la PresaThe Arroyo de la Presa site (41PS800) is an open campsite located along the banks of the Rio Grande about half way between Presidio and Redford, Texas. Although the site is several hundred meters in length and occupies portions of several successive river terraces, only the uppermost part of the site has been investigated. In that area of the site, hunting and gathering groups repeatedly camped over a time span of about 1000 years, beginning around A.D. 700. While no definitive evidence of La Junta villager occupation has been found, the site has compelling evidence of contemporary and earlier non-villager occupations. Substantive archeological work in the Redford Valley stretch of the Rio Grande has focused on two distinctive types of sites, both dating to the A.D. 1200-1700 period. La Junta phase and Concepcion phase village sites (such as Polvo) occur on terraces along the river, while Cielo complex hunter-gatherer sites are positioned on high adjacent pediments overlooking the valley. The recent work at the Arroyo de la Presa site has provided chronological and behavioral data for another kind of site from this period, a hunter-gatherer campsite immediately next to the river. Findings from the site help fill in some of the gaps in our understanding of use of the river valley in Late Prehistoric times. Arroyo de la Presa was originally documented by Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) archeologists Nancy A. Kenmotsu and Barbara Hickman in January 2000. The site was tested in 2000 by author William A. Cloud of the Center for Big Bend Studies (CBBS) of Sul Ross State University. Cloud directed more extensive excavations in 2001. The project, sponsored by the Environmental Affairs Division of TxDOT, was initiated prior to reconstruction and rehabilitation of Farm-to-Market (FM) Road 170. The investigations were confined to the relatively narrow highway right-of-way (ROW) on the uppermost terrace area of the site. Data recovered indicate there were a number of prehistoric occupations in that portion of the site dating between approximately A.D. 700-1650. The stratigraphy in the investigated portion of the site proved to be very complex, the result of sloping former surfaces trending both toward the river and downstream, and cut-and-fill episodes from flooding of the Rio Grande and a nearby tributary drainage. Most of the deposits observed at the site were fine sands laid down by overbank flood waters of the river, yet sheetwash on the sloping surfaces also contributed to the deposition. Eight stratigraphic units or zones were delineated. Zone IV proved to contain the most concentrated prehistoric deposits uncovered, roughly dating to the period A.D. 700-1250. The overlying Zone III contained cultural deposits that appear to date between A.D. 1250-1600. All 13 of the archeological features documented at the site are thought to have been constructed and used during formation of one of these two zones. The Arroyo de la Presa site seems to have been occupied primarily by hunter-gatherers, although some findings suggest that members of nearby La Junta villages also may have conducted activities there at times. Depth limitations for the highway project prevented a thorough investigation of all of the older (and deeper) occupations. At least one cooking feature, a hearth remnant, was documented that dates to around 3,000 years ago (1060-880 B.C.) Eroded cooking stones and chipped stone debris suggests an ephemeral Late Archaic occupation, perhaps a short-term campsite. During the Late Prehistoric period (roughly A.D. 700-1535), agave, yucca, or sotol hearts were apparently being processed at the site in a large earth oven or ovens. Evidence of this activity comes from the recovery of small plant fibers (not specific as to species) in several features. This processing activity occurred during the beginning of the period (A.D. 660-860) as well as during later times (A.D. 860-1020 and A.D. 1040-1260), suggesting that plant baking occurred on a regular basis. Rock-lined pits served as "ovens" within which the succulent hearts were allowed to slowly cook (bake) over a period of several days. Historic accounts of this process indicate the hearts were sun-dried after being recovered from the oven, and then ground or pounded into a flour-like matrix, which was mixed with water and ultimately made into edible cakes. Earth oven features are widely spread across the Trans-Pecos region. They first appeared in the archeological record in this region during the Middle Archaic period (at least as early as 2000 B.C) and persisted into the late nineteenth century. The Arroyo de la Presa evidence also documents the use of small stone-lined hearths between A.D. 780-1020. These hearths may have been used for cooking or warming, or perhaps both. Four such hearths have been uncovered at the site and all date to this relatively narrow window of time, although it is likely that larger excavation areas may have turned up earlier or later examples as well. One of the most informative features excavated at the site was a large pit measuring over 2 meters in diameter that contained a wide variety of material goods and botanical remains. Interpreted as a trash pit and dated to the middle portion of the Late Prehistoric period (A.D. 1040-1260), this pit has provided a great deal of behavioral data. Within it were burned remnants of plants that appeared to have been processed as foodstuffs: agave, yucca, or sotol fibers, saltbush seeds, mesquite beans, and goosefoot or pigweed seeds. Small burned bones from the pit, most of which appeared to be from rodents (at least one large lizard was represented), provide additional dietary information for this time. Interestingly, no fish remains or artifacts associated with fishing (e.g., notched pebbles) were found in the pit despite the location of the site along the river. Other items recovered from this feature include a faceted hematite pebble, 35 ground stone fragments, an arrow point with attributes of both the Livermore and Perdiz types, an etched pebble, a fossil fragment (Turritella sp.), and two pieces of daub or baked mud plaster. The arrow point may provide evidence of a linkage between the earlier Livermore phase and the succeeding La Junta phase and Cielo complex, adding weight to the suggestion that the widespread Perdiz point originated within cultures of the eastern Trans-Pecos. Presence of the two pieces of daub, which are typically associated with mud-plastered jacal houses, suggests that such structures were present nearby. The radiocarbon age of the trash pit overlaps with the early La Junta phase. A burned rock pavement at the site, apparently constructed about the same time as the trash pit (A.D. 1040-1290; A.D. 1160-1270) and measuring over 2 x 4 meters, appears to have been used to parch mesquite beans. Burned mesquite pods and seeds were the only potential plant foodstuffs recovered from this feature. Mesquite and saltbush limbs were apparently placed on a sloping ground surface, ignited, then covered with a pavement of river cobbles 2-3 courses thick. It is thought that the mesquite beans were parched on the upper surface of this pavement. Ethnographic documentation of mesquite processing in the American Southwest indicates that after being parched the beans were typically pounded into flour with a mortar and pestle. The function of several different pit features at the site was not as discernable. One of these had a slight bell-shape, a diameter of about 65 centimeters, and contained four clustered burned rocks on its base. This feature provided a date of A.D. 780-980, but lacked botanical remains. Three other pits with unknown functions were dated to the end of the Late Prehistoric period or to the subsequent Protohistoric period (A.D. 1420-1650; A.D. 1420-1490; and A.D. 1420-1800). One of these was extremely intact, suggesting that it had been intentionally covered shortly after being used. This circular pit had a diameter of about 1.1 meters, a depth of at least 50 centimeters, and contained what appeared to be digging stick marks along one of its sides and in portions of its base. The areas of the base that lacked these marks contained well-preserved charcoal "logs" that were identified as mesquite, cottonwood/willow, and saltbush. A couple of burned pigweed or goosefoot seeds in the lower fill of the pit may indicate what was being processed. Another of these pits also had charcoal lining its base and was found to contain a few burned sacaton grass seeds. Whether these specific plant seeds were parched within these respective pits or were fortuitous additions is unknown at this time. What appeared to be a large pit loosely filled with burned rock yielded evidence of prickly pear processing. Several burned fruit fragments and a burned seed recovered from its matrix attest to this activity. Based on our understanding of the stratigraphy at the site, this feature most likely dates from about A.D. 1250-1600. The earliest arrow points recovered at Arroyo de la Presa are of the Livermore type, a type long suspected as being one of the first arrow points that were used in the region. One of these points was uncovered up against a small piece of charcoal that yielded a date of A.D. 690-890. This is the earliest known date for Livermore points in the region. Other arrow points recovered consist of several other Livermore and Livermore-like fragments, three Toyah or Toyah-like specimens, four small, untyped side-notched specimens, an untyped corner-notched specimen, the aforementioned point with both Livermore and Perdiz attributes, a Perdiz point, and several probable Perdiz point fragments. In general, the different point styles suggest that different groups used the site at different points in time. It is likely that both Livermore phase and La Junta phase peoples, and perhaps Cielo complex folks, are represented by these arrow points. Pottery was scarce at the site, but five plain brownware body sherds were recovered, representing two different varieties. Four of the sherds are very similar and may be from the same vessel. Neither brownware variety could be identified with a known pottery type and were termed Undifferentiated Chihuahuan Brownware I and II. Similar pottery has not been previously reported from the district. Petrographic analysis and Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA) suggested both emanated from unknown Chihuahuan origins. Although previous work has suggested pottery did not appear in the La Junta area until about A.D. 1200, based on its stratigraphic position within the site deposits, the single sherd of Undifferentiated Chihuahuan Brownware II could date as early as A.D. 700-900. Several of the Undifferentiated Brownware I sherds were found on a possible living surface adjacent to the trash pit and may date to the same approximate time of that feature (A.D. 1040-1260). Additional details and interpretations are presented in New Insights. Also found at the site were stream-rolled pebbles bifacially-notched on opposing ends, artifacts previously only documented in riverine archeological contexts. These notched pebbles, which have been interpreted as weights for fishing nets, were found vertically distributed at the site indicating use through time. Interestingly, fish bones were not found in any of the features or excavation units, possibly suggesting this resource, if exploited, was cooked and eaten in another portion of the site or a different locale altogether. Several of the items recovered are materials, or are made from materials, that do not occur naturally in the immediate area, suggesting trade played a role in their presence. Included among these exotic items are an extremely shiny metallic pebble identified as specular hematite, a discoidal stone bead, and an Olivella sp. shell. Both of the stone items were probably from distant sources, such as areas of New Mexico or northern Mexico, while the shell appears to be of a species native to the Pacific coast of Mexico. One or more of these items may have passed through Casas Grandes, a major redistribution center in northern Chihuahua thought to have had influences on the La Junta area during the Late Prehistoric period. Most of the findings from Arroyo de la Presa agree with our understanding of hunter-gatherer activities and tool kits in the region. However, some of the pit features, the ceramics, the daub, and the possible trade items are suggestive of a presence at the site by more sedentary folks, perhaps small groups from nearby agricultural villages procuring selective resources along this stretch of the river. If so, the radiocarbon dates suggest that sedentary occupations may have begun before the traditional beginning date of the La Junta phase (A.D. 1200). Most of the site features seem to represent plant processing features, while evidence of hunting, trapping, or fishing were relatively minimal. The site has provided the first indication in this portion of the region of saltbush seed, sacaton grass seed, and goosefoot or pigweed seed exploitation. Furthermore, the botanical data from the site have provided indications of occupations during different seasons of the year-spring (agave, sotol, or yucca processing), late spring/early summer (sacaton grass seed processing), and mid- to late-summer (goosefoot or pigweed, mesquite bean, saltbush seed, and prickly pear fruit processing).Thus the data recovered at the site has greatly strengthened our understanding of human ecology along the river during the Late Prehistoric period. Additional excavation in unexplored areas of the site would clarify how the area was used through time by various cultural groups. Shiner and WilliamsThe Shiner site (Shafter 6:1) is a multi-component site located along Alamito Creek over 20 kilometers north of the Rio Grande. This site and the nearby Williams site are the only confirmed Bravo Valley sites this far from either the Rio Grande or Río Conchos. Extending from the main stem creek beyond a tributary arroyo known as Denman Draw, the Shiner site covers a relatively large area several hundred meters in extent. It was brought to Kelley's attention in the summer of 1937 by V. J. Shiner, for whom the site was named. About a year later, when Kelley, Lehmer, and Thomas N. Campbell were investigating archeological sites throughout the Big Bend, excavations were carried out at the site over the course of several days. Kelley and Campbell documented three cultural strata exposed in the cut bank of Denman Draw: 1) a La Junta phase occupation eroding from very near the surface; 2) a probable Late Archaic occupation exposed ca. 1.8-3.7 meters below the surface; and 3) an apparent Middle Archaic occupation exposed ca. 3-5.2 meters below the surface. An Almagre dart point and numerous flakes and chips were found eroding from the lowest cultural strata in the cut bank, while a possible knife was recovered from the more ephemeral middle stratum. Two pithouses were excavated and a third documented within the uppermost strata. Both of the excavated houses were burned, rectangular in shape, and closely resemble La Junta phase structures that were excavated a short time later at the Millington site. House 1 contained small post molds in its corners and along the east wall. Charred reeds and grass found along the west wall and on the floor show that the structure's walls and roof were of fragile jacal construction. Numerous flakes and chips were found on the unprepared floor of this structure, although formal tools were lacking. House 2 was about twice as big as House 1, and shared a wall on its east side with House 3, which was not excavated. Compared to House 1, House 2 was constructed within a shallower pit and contained an adobe floor, with adobe curbs around the periphery that extended upward to ground level; walls of jacal construction were inferred to have rested upon the smoothed tops of the curbs. A flexed infant burial was found in a pit within this house and on the floor above it were two dart points/knives and two pieces of red pigment (one was faceted) that likely were associated with the inhumation. Additionally on the floor of the house were two cloud-blowers—large tubular stone pipes. Ceramic sherds typical of the La Junta phase—El Paso Polychrome, Villa Ahumada Polychrome, and Chihuahua Polychrome—were found in association with the houses and on the eroding surface of the site. Documented during the survey, but not excavated, was the Williams site (Shafter 6:2) located about four miles upstream from the Shiner site. Along a 100-meter stretch of a cutbank along Alamito Creek were hearthstones, possible house floors, ashes, charcoal, and artifacts, including Perdiz points and El Paso Polychrome sherds. Also discovered within this strata was a deteriorated human burial in association with a broken, untyped Black-on-White pot, possibly a Chihuahua Polychrome from Casas Grandes. The inhumation was flexed in a shallow grave which Kelley suspected had been dug into a house floor. Recent attempts to relocate the Shiner and Williams sites have yet to succeed, in part due to the scale and lack of detail on the topographic maps used in the 1930s. The sites' remote settings in the back country, well off the beaten path, have also helped to conceal their locations. However, efforts are underway to relocate these sites, especially the Shiner site, to evaluate future research potential. Unexcavated SitesAdditional Bravo Valley culture sites in the La Junta district have been documented by Kelley, Mallouf, and others, but none have been tested or excavated. These include at least five sites on the Texas side of the Rio Grande near the joining of the two rivers, Including the Kopenbarger site (41PS16), which is thought to be a Conchos phase village. Another of these sites is San Antonio de Padua (41PS58), which is owned and protected by the Texas Historical Commission. Three very important La Junta village sites known from Spanish accounts on the Mexican side include San Francisco on the west side of the Río Conchos; Guadalupe, which is thought to underlie the modern city of Ojinaga; and San Antonio de los Puliques located a short distance downstream of the confluence. Other unexplored La Junta sites are known to (or should) exist downstream from the confluence in the Redford valley; upstream along both sides of the Rio Grande as far as the Ruidosa area; and upstream along the Río Conchos as far as Cuchillo Parado. Collectively, the unexcavated La Junta sites represent tremendous untapped archeological research potential. Given the location of the Shiner and Williams sites, it is very likely that additional "outlying" Bravo Valley sites are present and yet to be documented along the major tributaries joining the two rivers within the La Junta district. Most of these are probably quite small hamlets or special purpose sites. There are also scattered indications of La Junta-related occupations in Big Bend area rockshelters located tens of miles outside the district.

|

|