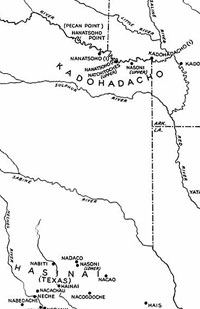

John Swanton's map showing the approximate

locations of some of the named Caddo groups and villages,

as recorded by the Spanish and French in the late 1600s

and early 1700s. From: Source Material on the History

and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians, 1942, Smithsonian

Institution.

|

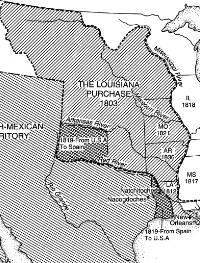

No boundaries were mentioned in the

terms of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. The boundary between

Louisiana and the Spanish dominions remained uncertain

until defined by the 1819 treaty negotiated by the U.S.

Secretary of State and the Spanish Minister in Washington.

From Carter, 1995, Caddo Indians: Where We Come From.

|

|

Caddo history begins with The Old People, "Kee-oh-na-wah'-wah

ha-ee-may'-chee", who settled in the valley of Red River

and uplands traced by tributaries draining into the river.

In that place, The Old People became strong and prosperous,

increasing in number and occupying greater territory. Descendants

of the Old People say—Caddo people are like the "limbs

and the twigs."

The first historical documents, written by Spanish

and French explorers in the mid-1500s and late 1600's, describe

individually named communities of Caddo, some quite large

and others mere farmsteads. Interrelated communities were

identified as belonging to one of three geographically separate

branches of the Caddo nation: Cadohadacho along the great

bend in Red River, Natchitoches farther down Red River where

the present Louisiana city of that name stands, and Hasinai,

"Our People," in east Texas. Over time, "hadacho"

meaning sharp was dropped from Cadohadacho and the people

were simply called Cado or Caddo. Spanish officials heard

about "the great kingdom of Tejas" before introducing

themselves to the Hasinai late in the 17th century. The name

for the State of Texas comes from this Spanish spelling of

a Caddo word "taysha," that means "friend"

or "ally".

[Prior to 1874, the word Caddo (or Cado) referred

to the Cadohadacho. Depending on context, we use "Caddo"

to mean Cadohadacho and, more generally, to mean all of the

Caddo-speaking peoples. For most references to historical

events prior to the late 1800s, it means Cadohadacho. By the

early 1800s many formerly independent named groups had joined

up with the Cadohadacho and all were often referred to as

the Caddo.]

Caddo leaders were skillful in arranging peaceful

alliances with neighboring Indian groups. Their powerful influence

and political astuteness became historically and politically

significant during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

when their homeland became a borderland between Louisiana

Territory and Spanish-Mexican Territory called the Province

of Texas. Spanish missionaries, military leaders, and government

officials, French traders and governors, Mexican and American

Presidents and officials vied for their support.

From the beginning of relations with Americans

in the early 1800s, Caddos pledged and worked to keep a policy

of peace and friendship with the United States. Exactly nine

years after the signing of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803,

Louisiana was admitted as the eighteenth state of the Union.

Dehahuit, the Grand Caddo, a leader whose influence and leadership

extended beyond Caddo, Natchitoches, and Hasinai to allied

tribes, was soon invited to a meeting with the first American

Governor of Louisiana, William C. Claiborne. Saying that he

spoke for the President, Claiborne asked for the continued

friendship of the Caddo people and emphasized that the current

disagreement between the United States and Spain was a dispute

between white people. He urged, "Let the red man keep

quiet, and join neither side." Dehahuit's cautious response

granted his loyalty but not his lands to the Americans.

|

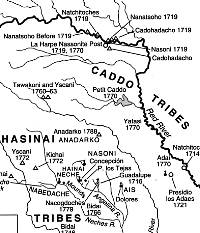

Rivers and terrain of the Caddo Homeland.

|

Caddo(Cadohadacho), Hasinai, and

closest neighbors in the eighteenth century. From Carter,

1995, Caddo Indians: Where We Come From.

|

William C. Claiborne, first American

Governor of Louisiana. Portrait in the Louisanana State

Museum.

|

|

|

| |

You request that our wars in future may be

against the deer only, that is what we ourselves desire, and

happen what will, our hands shall never be stained with white

man's blood. Your words, which I have this day heard, shall

be imprinted on my heart, they shall never be forgotten, but

shall be communicated from one to another, till they reach

the setting sun. . . .

My father was a chief; I did not

succeed him till I was a man in years. I am now in his place,

and will endeavor to do my duty, and see that not only my

own nation, but other nations over whom I have influence,

shall properly conduct themselves.

Grand Caddo Dehahuit's

reply to Louisiana Governor Claiborne's address, 1806

|

|

|

View from Stormy Point. Photo by Cecile

Carter.

View from Stormy Point. Photo by Cecile

Carter. |

Strong and gifted Caddo leadership was not enough

to overcome epidemics that killed thousands, or the flood

of immigrants that came to their homelands as the United States

advanced its western frontier.

Early in 1835, Caddo leaders signed, by marks,

a memorial addressed to the President of the United States.

Written for them in formal English language, the message may

or may not have been approved by the Caddo leaders. Parts

at least were true to their sentiment—"heavy news"

had put the Caddo "in great trouble." Their last

American agent had told them he was no longer their agent

and said he "does not know what will be done with or

for the Caddo." Having placed their faith in assurances

by representatives of the United States that no white man

would ever settle on Caddo lands for more than thirty years,

it is doubtful that the leaders of the Caddo nation now intended,

or even knew, that the final paragraph offered "all our

lands" for sale.

|

Stormy Point on Ferry Lake (Caddo Lake)

February 1993. There is a good possibility that the Grand

Caddo Dehahuit, who died in 1835, was buried near Stormy Point,

a favorite crossing to Shreveport as late as the 1860s. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

|

| |

To his excellency

the President of the United States:

The memorial of the undersigned,

chiefs and head men of the Caddo nation of Indians, HUMBLY

REPRESENTS:

That they are now

the same nation of people they were, and inhabit the same

country and villages they did, when first invited to hold

council with their new brothers, the Americans, thirty years

ago; and our traditions inform us that our villages have been

established where they now stand ever since the first Caddo

was created, before the Americans owned Louisiana; the French

and afterwards the Spaniards, always treated us as friends

and brothers. No white man ever settled on our lands, and

we were assured they never should. We were told the same things

by the Americans in our first council at Natchitoches, and

that we could not sell our lands to any body but our great

father the President. Our two last agents, Captain Grey and

Colonel Brooks, have driven a great many bad white people

off from our lands; but now our last-named agent tells us

that he is no longer our agent, and that we no longer have

a gunsmith nor blacksmith, and says he does not know what

will be done with us or for us.

This heavy news

has put us in great trouble; we have held a great council,

and finally come to the sorrowful resolution of offering all

our lands to you which lie within the boundary of the United

States, for sale, at such price as we can agree upon in council

one with the other.

|

|

|

| |

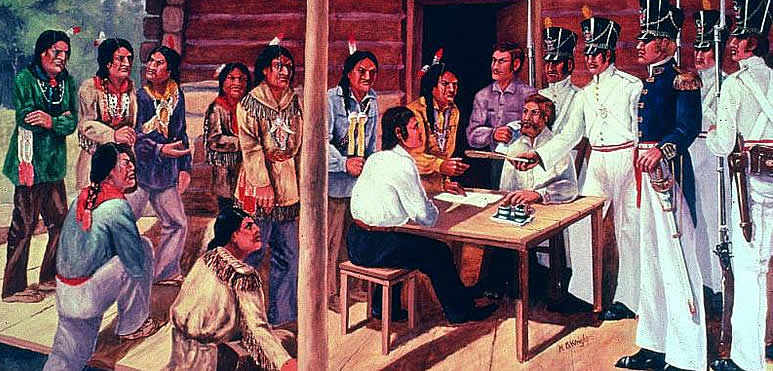

After waiting six months for a response from

the President, the Caddos received a message that their former

agent was at the agency house (near present Shreveport) and

ready to negotiate with them. There was no true negotiation.

The Caddo had no official counsel. Their former agent made

it clear—Caddo people could sell the land of their forefathers

for what the government now offered or wait only a short time

for the white people to take it away without payment.

|

|

|

| |

I...am again sent...to obtain that

from you which is of no manner of use to yourselves, and which

the whites will soon deprive you of, right or wrong, and am

ready to give for it what you cannot otherwise obtain, or

long exist without, in this or any other country. I am instructed

to deal liberally with you.

U.S. Agent, Jeheil Brooks

June 25, 1835

|

|

|

| |

Thus coerced, Caddo chiefs, headmen, and warriors

drew their marks by names pointed out to them at the Treaty

signing on July 1, 1835.

|

|

|

Caddo Indian Treaty of Cession, July 1, 1835.

Mural in Louisiana State Exhibit Museum, Shreveport, courtesy of

Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism.

|

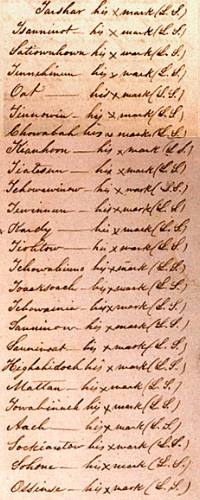

Marks of Caddo chiefs, headmen, and warriors

on the Caddo Indian Treaty of Cession, July 1, 1835. Click

to see entire signature page of treaty.

|

The Caddos gave up nearly a million acres of

ancestral land. According to the Treaty, they would receive

$80,000-thirty thousand in goods and horses on signing the

Treaty, $10,000 in money within one year, and $10,000 in money

each of the following four years. In exchange, the Caddos

were required to move "at their own expense out of the

boundaries of the United States and the territories belonging

and appertaining thereto" within the period of one year

after signing the treaty, and "never more return to live,

settle, or establish themselves, as a nation, tribe, or community

of people, within the same."

For what do you morn? Are you not starving

in the midst of this land? And do you not travel far from

it in quest of food? The game we live on is going further

off, and the white man is coming nearer to us; and is not

our condition getting worse daily? Then why lament for the

loss of that which yields us nothing but misery? Let us

be wise, then, and get all we can for it, and not wait till

the white man steals it away, little by little, and then

gives us nothing...

Tarshar (Ta'sha)principal Caddo

leader speaking to his grief stricken people before the

cession of Caddo lands in 1835

|

Tarshar his X mark

Tsauninot his X mark

Satiownhown his X mark

Tennehinun his X mark

Oat his X mark

Tinnowin his X mark

Chowabah his X mark

Kianhoon his X mark

Tiatesun his X mark

Tehowawinow his X mark

Tewinnun his X mark

Kardy his X mark

Tiohtow his X mark

Tehowahinno his X mark

Tooeksoach his X mark

Tehowainia his X mark

Sauninow his X mark

Saunivoat his X mark

Highahidock his X mark

Mattan his X mark

Towabinneh his X mark

Aach his X mark

Sookiantow his X mark

Sohone his X mark

Ossinse his X mark

|

|

The Caddo nation gave up nearly one million

acres of ancestral land by the Treaty with the United States

in 1835. Sections showing Caddo land cession in 1835 Treaty

outlined and designated 202 on Louisiana and Arkansas maps,

Indian Land Cessions in the United States compiled

by Charles C. Royce,1897, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau

of American Ethnology.

|

...the Indians were asked for an amount

of land large enough to be covered by a hide. After the

bargain the hide was cut into thin strips and stretched

around a large plot of land and claimed as per agreement....the

whites raided the Indians, drove them from their villages

and took a portion of their crops. After the treaty a part

of the money was paid, but a part never was paid.

testimony of Mary Inkinish,

Fort Cobb, Oklahoma, August 25th, 1929

Mary Inkinish was a child when her family left

Louisiana but her memory of the move remained strong. In 1929,

when she was past 100 years of age and the oldest member of

the Caddo Indian tribe, she recalled things that happened

during and after the 1835 Treaty. She did not speak English.

One of her sons interpreted as she told how the Caddos did not

understand the extent of the land sold, and that the money

was never paid as it should have been.

The Caddos moved to different places at different

times. The first to leave looked for new homes in Texas. Mary

Inkinish was with a smaller group that traveled into Mexico

before rejoining the Caddos in Texas. The last to leave followed

Red River to Washita River in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma)

without entering Texas. All were virtually homeless for the

next twenty years.

|

Mary Inkinish retained strong memories

of events during and after the 1835 Treaty when she was past

100 years of age. Courtesy Western History Collection, University

of Oklahoma Library.

|

|