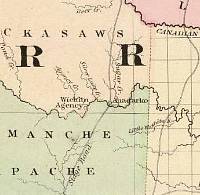

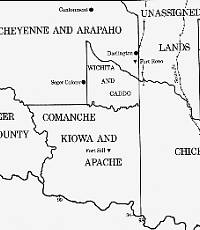

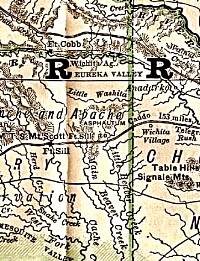

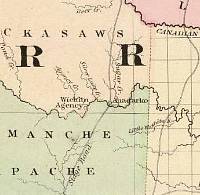

Wichita Agency area, 1874 map by

Asher and Adams. Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection.

Click images to enlarge

|

|

In 1859 official representatives of the United

States presented Caddo chiefs and headmen with the Arbuckle

Agreement that assured Caddos they would occupy a country

belonging to the United States, and not within any State,

where none could intrude upon them; and they would remain,

they and their children, as long as the waters should run,

protected from all harm by the United States. The Superintendent

of Indian Affairs defined boundaries for that country that

were adequate. The certain promise of permanency and protection

satisfied the Caddos' greatest need. In accord with the agents

for the United States government, the chiefs and headmen accepted

the Arbuckle Agreement on July 1, 1859. Upheaval created by

the Civil War soon canceled the Agreement's certainty.

During the white man's war most Caddos spent

five debilitating years as refugees in Kansas. Others sought

protection with the Seminole Nation or at Whitebead Hill in

the Chickasaw Nation. It was 1867 before all returned, only

to find their houses ruined, fields and fences destroyed,

livestock stolen and large sections of their assigned territory

taken away. Houses could be rebuilt, fields replanted, and

new livestock raised, but it was not possible to gain self-sufficiency

through farming, hunting, and trade without the security of

a permanent location with adequate acreage.

Even as the main body of Caddos were returning

to their Washita River valley home sites, U. S. agents were

negotiating a peace treaty that gave the southern half of

the Leased District to warring Comanches and Kiowas. The treaty

ignored the Arbuckle Agreement that assigned all of the land

from the Chickasaw line to the 100th meridian and from Red

River to the Canadian River to peaceable Caddo, Wichita, and

affiliated tribes. The Agreement was ignored again in 1869

when an Executive Order located Cheyennes and Arapahoes on

a tract overlapping Caddo territory below the Canadian River.

Caddo leaders defended their land boundaries

as best they could. They held Council with Agents, pooled

their meager funds, sent representatives with interpreters

to plead their case at the nation's capitol. But, the last

years of the 19th Century passed without a secure land title.

During that time, much was learned about coexistence in a

world dominated by Americans endowed with skills yet to be

acquired by Caddo people.

Jose Maria, Iesh, the Anadarko whose

balanced leadership and wisdom guided Caddos, Hainais, and

Anadarkos during turbulent years in Texas, died before the

end of the Civil War. Guadelupe, Nah-ah-sah-nah, was

the accepted leader following the Civil War. Born in 1825

near Natchitoches, Louisiana, he died in 1877. Caddo George

Washington (Sho-ee-tat), the recognized leader of the Whitebead

Caddos before, during, and after the Civil War, died in 1883.

In 1865 Indians from all of Indian Territory

gathered for a Peace Council held in an area on the Washita

River that covered the entire present city of Verden, Oklahoma.

Disorder and uncertainty had ruled the Territory since the

beginning of the Civil War. The grantees of protection by

the Federal Government was withheld. The Confederate Government

made elaborate offers of protection that seemed, in the beginning,

a better chance for the Indians to maintain their existence.

Indian leaders soon learned that Confederate promises were

never more than spoken words, real protection did not exist.

Errant Plains Indian bands and Texas bandits drove off herds

of Indian cattle and horses without hindrance. The white man's

war created dissension among some tribes. There was fear that

the Plains Indians would go on the war path against settled,

agricultural tribes. Indian leaders realized that inter-tribal

unity was imperative if they wanted to survive.

The 1865 Peace Council was called to organize

an Indian league. A compact was signed by George Washington,

Tiner, and two other delegates from the Reserve Caddo Nation.

It was also signed by delegates from the Five Civilized Tribes

in the eastern Territory, Osages from the north, Delawares,

and the Kiowas, Comanches, Apaches, Cheyennes and Arapahoes

(called the Plains Indians from the west). Texas officials,

who had considered the possibility of an alliance with all

the Indians in order to help Texas protect her frontier, sent

representatives but they played no part in the council.The

compact incorporated a motto--the great principal of Confederate

Indian tribes-- "An Indian shall not spill an Indian's

blood."

As soon as federal boarding schools for Caddo

children were opened in 1870-1871, Guadelupe and Caddo George

Washington not only insisted that boys and girls attend, they

kept close tabs on their progress. Children were taught math,

geography, the reading and writing of English as well as New

Testament and Genesis lessons by members of the Society of

Friends (Quakers).

|

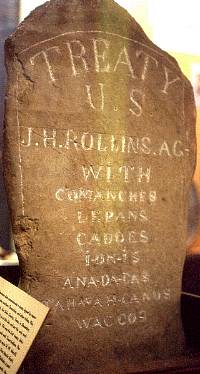

The Fort Arbuckle Agreement concluded

on July 1, 1859, set the boundaries for land within

the Leased District of Indian Territory that Caddo,

Anadarko, and Hasinai chiefs and headmen were assured

"they would remain, they and their children, as

the waters should run, protected from all harm by the

United States."

|

|

|

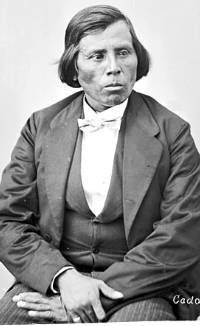

Sho-ee-tat, George Washington, was an active

leader of the Whitebead Caddo band before, during, and after

the Civil War. 1872 portrait taken when delegation visited

Washington. National Anthropological Archives..

|

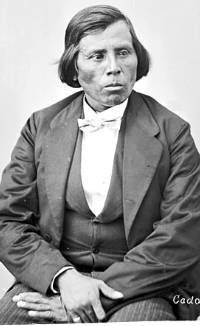

Guadelupe, Nah-ah-sah-nah,(Warloupe) was

accepted as a leader of Caddo and Hasinai communities following

the death of Iesh. 1872 portrait taken when delegation visited

Washington. National Anthropological Archives.

|

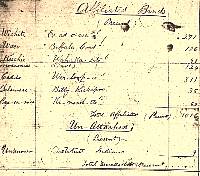

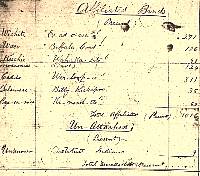

Wichita Agency rolls (census) for 1869.

Courtesy Cecile Carter.

|

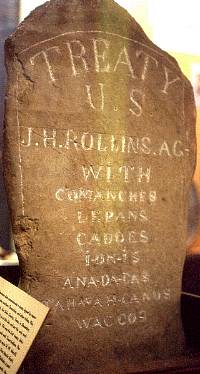

The Camp Napoleon Monument, dedicated in

1930, is located on the high school campus in Verden, Oklahoma

. It honors representative of Indian tribes who signed a compact

in 1865 to preserve the peace, happiness, and protection of

their people. The maker is due to the efforts of noted historian

and President of the Oklahoma College for Women, Dr. Anna

Lewis.

|

Butler School, 1871. Josiah Butler taught

Caddo children at this U.S. Indian School built in between

present Fort Sill and Lawton, Oklahoma, 1870.

|

|

| |

After the Caddo children had been in school a few weeks,

George Washington came in one evening and the next morning

he was in the school room when I got up and there he stayed

until bed time, having his meals and drink carried to him

and his team cared for by the children. After all was over,

ending with 'singing geography,' from outline maps, I left

the room. Very soon afterward I heard uproarious laughter

in the school room. This was repeated the third time, when

I slipped out and, looking in the window, found Washington

examining his children to see if they could do anything without

my being present. While he could talk English quite well,

he did not know a thing about the books, charts and maps and

so could not use the points at all, and so the children laughed

at him. He then got behind the class and made each one in

turn use the points and read and spell in English, going over

all that I had through the day and giving the meaning in Caddo.

He knew they knew no English when they came and, in this way,

he proved them as to how much they had learned, and he was

satisfied.

Josiah Butler, pioneer teacher at the Comanche-Kiowa

Agency school on the site between present Fort Sill and Lawton

1870-1873

This morning school was visited by Guadelupe, principal

chief of the Caddoes, who made a long speech to the children,

in which he told them that all white children go to school;

that they do not talk and laugh out loud—they tried hard

to learn; and he wanted them to be like the white children—mind

all their teachers tell them, and try hard to learn. He also

told them that at night they went to bed to sleep at once;

not talk and play, so as to keep all in the house awake.

Thomas C. Battey, teacher at the Wichita Agency

school, 1871

As a child his mother sent him to council meetings. He

became an interpreter and before the old chief died, he called

a council. He told him [her father] to come. Said "I

want to talk to you all and tell [you] I'm getting old. I'm

not going to be with you long. He [Enoch Hoag] should have

been in here, not me. It rightly belongs to him."

Lillie Whitehorn, 1978, daughter of Enoch Hoag,

the last of the traditional Caddo chiefs

|

|

|

Stanley Edge, interpreter for the

last of the traditional chiefs, was sent to Carlisle

Indian school. Western History Collections, University

of Oklahoma.

|

The Riverside Indian School near Anadarko, Oklahoma, is

the oldest federal government school for Indians in continuous

operation. Photo by Steve Black. |

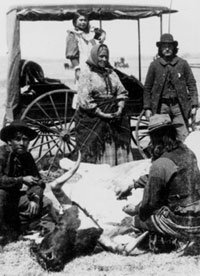

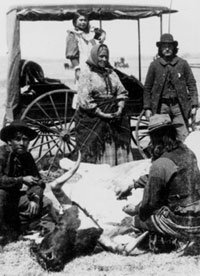

Inkanish family butchering steer

issued at Fort Still, Oklahoma in 1894. Archives and

Manuscripts Division, Oklahoma Historical Society.

|

|

Caddo elders traditionally schooled a future

caddi (cah-de, a principal leader, chief) from early

childhood. By the time he assumed his hereditary leadership

position, he was prepared with the necessary knowledge and

skills. Forward-looking leaders in 1870 viewed English language

skills as vital for the preparation of the next generation

of leaders. Their nation's most recent history warned against

blind acceptance of oral and written words that led to misunderstanding.

Every council with Americans required an interpreter; every

treaty marked with an X at the end of unreadable names had

failed to meet expectations. Some failures were the result

of hidden meanings or untranslatable English words that were

ineffectively expressed by the interpreter. Words often had

different meanings for people of different languages. There

were times when even the most trusted, competent, interpreter

was unable to transmit the nuance of a word or phrase. Many

interpreters were thought trustworthy, but Caddo interests

were not their prime concern. Wisdom demanded that future

Caddo leaders be as adept in English as well as their native

language.

George Washington died in 1883; Guadelupe in

1887. Caddo Jake, Hah-cah'-yo kee na say a ("once

lived in white house") was generally recognized as principal

chief 1890-1902). Community headmen, also hereditary leaders,

played an increasingly prominent roll in protecting and guiding

the rebuilding the nation whose culture was nearly a thousand

years older than that of the United States of America they

were compelled to accommodate.

Major communities grew, much as they always had, from a nucleus

of related families. A man who married a woman from another

community usually went to live as part of her family group.

All lived in substantial log or frame houses on farmsteads

of ten or more acres. Women kept the houses clean and tidy

and tended garden patches; men labored fencing fields, cultivating,

and raising cattle and horses. Lack of industry and effort

did not slow their progress toward self-sufficiency. Blizzards,

drought, and poor soil; a pestilence of grasshoppers and epidemics

of whooping cough, measles, and influenza; Comanche raids,

and Texas horse thieves did.

Rations distributed from the Agency staved off

the possibility of starvation and provided a vague semblance

of former days spent in hunting deer and chasing of buffalo.

The Agent made a yearly census listing the names of headmen

and the number of men, women, boys, and girls in their "band".

Headmen were appointed "beef chiefs." Traveling

ten or more miles on horseback, in wagons, or in hacks, families

arrived to set up overnight camps. Each "beef chief"

was given a ticket showing his name, the name of his band,

his number on the census roll, the number of persons in his

family, the total number of rations they were entitled to

receive at each issue, and the dates of the issues.

These tickets were turned over to the women

who were admitted in line at one door of the commissary, exited

at another. Their task was about as pleasurable as standing

in a long check out line at Super Wal-Mart. An issue clerk

stationed with an interpreter near the entrance punched out

the date on the ticket and called out something like "one

of flour, two of sugar, one soap, and one baking powder."

The women passed the sacks they brought across a counter to

an assistant clerk who filled them with the measured amount

of flour, sugar, salt, beans, rice, baking powder, and soap

to which they were entitled.

High spirits roused when the beef was issued.

The cattle were in a corral where all could see them. Clerks

recorded weights as herders ran them over scales. They then

turned them into a narrow chute that opened onto the prairie.

The issue clerk, assisted by an interpreter, called out the

names of beef chiefs and pointed out the cattle apportioned

to them. The gate was thrown open and as cattle cleared the

chute, two to ten mounted Indians fell behind each one. The

average turnout was one per minute. Boys on ponies let out

a yell and shot arrows in the flank and neck. Men raised their

revolvers or Winchesters to spurt up dust, then shot a bullet

to make the steer stagger on three legs. When the animal fell,

women rushed out to begin the butchering. Thin strips were

cut and hung to dry over camp fires.

|

The Riverside Indian School across the Washita River

from Anadarko, Oklahoma grew from the first Wichita

Agency school that employed Tomas C. Battey as teacher

in 1871. 1899 photograph by Annette Ross Hume. Western

History Collections, University of Oklahoma. |

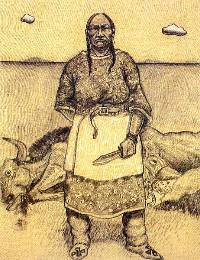

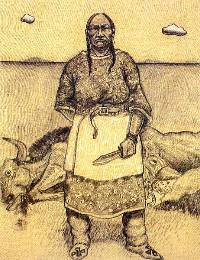

"Beef Issue at Fort Still"

painting by T.C. Cannon, son of a Kiowa father and a

Caddo mother. Courtesy of the Tee Cee Cannon Estate

and Joyce Cannon Yi, estate executor.

|

"Beef Issue, Woman Study,"

pencil drawing done T. C. Cannon in preparation of his

painting "Beef Issue at Fort Still. " Courtesy

of the Tee Cee Cannon Estate and Joyce Cannon Yi, estate

executor.

|

|

|

| |

"I do not know why it was but Caddos always loved

to camp. They'd go visiting other families and camp for two

or three days, maybe a week. Then, of course, they always

camped at dances."

Wimpy Edmonds, speaking of his grandparents

|

|

|

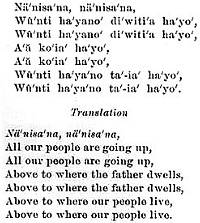

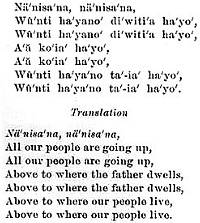

Ethnologist James Mooney who studied

the Caddo Ghost Dance in 1890-91, described this song,

"The sentiment and swinging tune of this spirited

song make it one of the favorites. It encourages the

dancers in the hope of a speedy reunion of the whole

Caddo nation, living and dead, in the "great village"

of their father above."

|

|

Camping was a favored pastime. Two or three

days, even a week of camping was usual while visiting the

homes of friends or attending a dance. Someone like the "rich

widow" Caddo Jennie would say, "I'm giving a dance"

and families from miles around would come to camp, eat, socialize,

and dance to the drum of old songs sung since time before

memory. The dances were not the dances pictured by people

who have only seen movies or gone to intertribal powwows.

They were, and still are, family affairs. Songs carrying stories

about the beginning of the Caddo people and important historical

events validate Caddo existence; frivolous songs cheer dancing

couples; morning songs greet the sun at the beginning of a

new day.

|

Camping is still a favored pastime for

many Caddo, especially during the summer for dances. Murrow

Dance Ground.

|

|

| |

In front of those who are dancing there is a pole and

on it hangs a portion of everything they are offering to God.

In front of the pole a fire is burning. Near by is a person

who looks like a demon. He is the person who offers the incense

to God, throwing tobacco and buffalo fat into the fire. .

.This pole and the fat for the incense-which has already been

burned-they offer to God. Every time a dance begins, a man

steps forward as a preacher does and tells the people what

they are to ask God for in the next dance.

Fray Francisco Cansanas de Jesus Maria, August

15, 1691

|

|

|

1892 Caddo dance party. Archives and Manuscripts Division,

Oklahoma Historical Society. |

John Wilson and John Inkanish. Archives

and Manuscripts Division, Oklahoma Historical Society.

|

|

When the Ghost Dance was introduced to Caddos

in 1890, they adapted it to long held religious beliefs. They

had their own songs, and they had a pole. From the time of

the oldest ancestors, Caddos believed: Ah-ah-ha'-yo, father

above, hears our daily prayers; he provides and protects us;

there is a world beyond this one where our people gather after

leaving mother earth. The pole was carved from the heart of

a tall cedar tree. Painted black on one side, green on the

other, it was erected with the black side facing north, the

green side south. The leader stood on the invisible dividing

line at the west side of the pole. Facing east, he began the

first song telling that the feather signifying the right to

lead the Ghost Dance was given to seven men. Sometimes a person

in the dance-in-a-circle would fall in a trance. On waking

from a trance the person would tell of a vision and a new

song would be made. Sometimes healing miracles occurred.

The Ghost Dance began in January 1889, when

a Paiute man named Wavoka (Jack Wilson) had a vision during

a total eclipse of the sun. He foretold of a coming natural

disaster that would swallow up the Whites and allow Indians

to return to their lands and way of life. Wavoka's vision

spread quickly among diverse groups across the Plains and

beyond. John Moon-head Wilson, from the Caddo tribe, was one

of the charismatic leaders who helped spread the Ghost Dance

in 1890. By taking part in the five-day dance, Indians believed

that they would be reunited with their loved ones in the ghost

world. The speed and fervor with which the movement spread

sparked panic among white settlers and authorities and figured

prominently in the events that led to the massacre at Wounded

Knee.

Ghost dancing relieved uncertainty that clouded

the hopes of Caddo people. The songs were a form of communication

with the great Father Above. White people did not understand

and wanted to take it away. Failed attempts to gain permanent

title to the land they lived on made them apprehensive that

the "Great Father" in Washington would take it away

if he chose to do so.

|

John Moon-Head Wilson, a Caddo man

who became one of the charismatic leaders of the Ghost

Dance movement in the early 1890s. Archives and Manuscripts

Division, Oklahoma Historical Society.

|

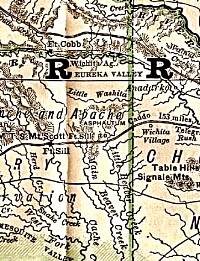

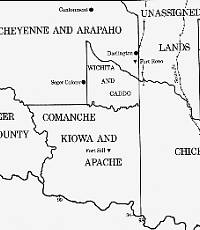

1884 map of Indian Territory showing the Wichita Agency

and area within which most Caddos settled. |

|

|

| |

White Bread, Chief of Caddos to his excellency The President

of the United States, February 3, 1888:

I am here only the representative of the Caddos—My

people live with the Wichitas, the Ionies [Hainai],

Anadarkoes, Tawaconies, Kechies and Southern Delawares. Each

one of these tribes once had a country and homes of their

own. Each tribe once had a country where their ancestors had

lived for generations and to which they were attached by ties

and associations as sacred and dear as those that cluster

in the memories and inspire the hearts of the white man for

his country and home. We have none now. . . .These things

have not happened to us because we were enemies of the white

man, and lived by rapine and bloodshed like many other tribes

of Red men. The story of our wrongs and sufferings is too

long to be told you now—I will not attempt it. . . .

We, the affiliated bands made war on no people, and lived

as best we could during the Civil War among the white people—After

the war, and after the Comanches, Apaches, and Kiowas had

made war upon the white people a treaty was made with them,

and our country, the home and country of the Wichitas for

generations back, was ceded to them, and the Wichitas and

affiliated bands, because of their peaceful lives and friendship

to the white man, and through their ignorance were not consulted,

and have been ignored and stuck away in a corner and allowed

to exist by sufferance.

These are simple truths only half told—I humbly ask

the great Father to take pity on his friendless and ignorant

children and have these things looked into, and if he finds

the story true that he will send for the Chiefs of the Affiliated

bands, with their interpreters, and council with them here,

to the end that we may have a country of our own, and if allowed

that that our present reservation, much of which is poor and

sterile, may be extended so that we can make a living for

ourselves, and raise our children in comfort and soon teach

them the white mans way—I am but an humble man, ignorant

and cannot talk as I would wish—and in order that the

great Father may know my thoughts I have spoken them and had

them interpreted to a friend and asked him to put them in

the white mans language for the great Father to read—I

hope our Father will give my words attention and some time

before long let us hear words of comfort that my people and

their friends may rejoice. I am done.

Punjo, Caddo interpreter

|

|

|

Bob Dunlap served as an interpreter for Whitebread, principal

chief 1902-1913. |

"Beef Issue at Anadarko" by Frederick Remmington.

From Davis, Richard Harding, 1903, The West From

a Car Window. Harper & Brothers.

|

|

Combining two Indian nations—Wichita and

Caddo—under an Agency titled Wichita and Affiliated Tribes

in 1859 has since tended to confuse anyone unfamiliar with

their separate histories. References to the Wichita Agency

and the Wichita Reservation compounded the confusion. It implies

the close association of unrelated members. The Caddo, the

Wichita, and Delaware were affiliated but Caddos, Anadarkos,

and Hainais were never affiliates, they were all of one blood.

Likewise, Wacos, Tawakonis and Keechis were never affiliates

of the Wichita, they were all of one blood.

In 1889 the federal government began appointing

commissions to "negotiate" with Indian tribes holding

large territories to break these up into small individual

allotments (160 or 80 acres) for each adult member of the

tribe and open up everything else to white settlers. In addition

to taking more Indian land, the process had the intended effect

of destroying tribal governments and forcing the integration

of Indians into American society. At the same time Indian

children were being separated from their parents and being

forced to attend boarding schools where they were taught in

English and forbidden to speak their native tongue.

The commission that dealt with Caddo and Wichita

lands was called the Cherokee or Jerome Commission, after

its chairman, David H. Jerome. The Jerome Commission, Presidential

appointees charged with the task of negotiating with the Wichitas

on the subject of accepting allotment of their lands in severalty,

actually had to deal with two individual Indian Nations—Wichita

and Caddo—each unwilling to accept the government's proposal.

Allotment in severalty meant giving each member possession

of a 160 or 80 acres, breaking up Indian Nations, and opening

unalloted land for white settlement.

Chairman Jerome opened the council in May of

1891 with words that echoed those heard by Caddos before signing

the treaty that ceded their Louisiana homeland to the U.S.

in 1835. Jerome's statement, another commissioner's remarks

and the response of Caddo Jake, Caddo principal leader, are

in the record of the proceedings.

|

Chief Whitebread, Caddo Principal leader (1902-1913),

had apprenticed under Caddo Jake. |

1890s photograph of Caddo house on

Oklahoma prairie entitled "Group of Four near Judge

Georg Parton's House." Photo taken by James Mooney

before 1896. National Anthropological Archives.

|

|

|

| |

You can get a living better than you do now, and that

is what we have come to tell you. The Government has a plan,

which if you will adopt and try your best to live up to, will

give you more comforts and better living to you, and your

families, than you have ever had before. . . The Government

of the United States is the only friend and the best friend

that the Indian has, and it is the Government of the United

States that sends this food here to feed these Indians every

day.

Commissioner Chair, David Jerome

Wichitas have "more land than you can use and more

than anybody in this nation can use and that is the reason

we are come to ask you to take a less piece."

Warren G Sayre, member of the Jerome Commission

The Government should give us time to send our children

to school and educate them and then it is time to send this

Commission. . .if "pity" were had on

the Indians, the Commission would "return to Washington"

and this time would be allowed. [Caddo Jake] said plainly

that the Wichitas were not able to take land in allotment,

were not able to take care of it, and that they wanted to

return to their farm work and "not sit around here

and talk for several days." The Wichitas had been

"quite a little while . . . fixing their country"

and felt that it was their own; moreover they preferred

to talk about "greater claims" and "old

claims" the Wichitas had against the Government,

as to how their lands were reduced to "this little

strip of land north of the Washita." They said their

reservation was "about the right size" and

they would like to keep the land for the next generation.

"Can you tell us how many children are coming?"

Caddo Jake, in Council with the Jerome Commission,

Anadarko, May 11, 1891

|

|

|

| |

The government's will could be stalled, but

it would prevail. The Caddo Nation would falter, but it would

survive. Strength lay in the people's ability to hold on to

distinctive Caddo traditions that bound them while throwing

away old ways that no longer worked.

|

|

|

The Riverside Indian School across the Washita River

from Anadarko, Oklahoma grew from the first Wichita

Agency school that employed Tomas C. Battey as teacher

in 1871. 1899 photograph by Annette Ross Hume. Western

History Collections, University of Oklahoma.

The Riverside Indian School across the Washita River

from Anadarko, Oklahoma grew from the first Wichita

Agency school that employed Tomas C. Battey as teacher

in 1871. 1899 photograph by Annette Ross Hume. Western

History Collections, University of Oklahoma.