"Caddo Indian Tribe Business

Committee and Friends on the steps of the Oklahoma State

Capitol Building, January 25th, 1929." Archives

and Manuscripts Division, Oklahoma Historical Society.

|

Frequently Asked

Questions Regarding Indian Law

Who is considered to be an Indian?

Indian tribes have the authority and power to

define their own requirements for membership. Tribal

membership is most frequently defined by blood quantum,

however...

read

more>>

|

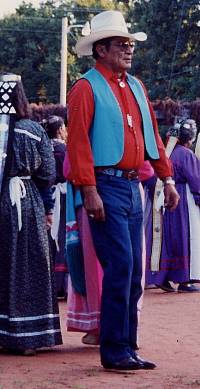

Leonard "Tony" Williams,

Chairman 1992. Williams was an enthusiastic Turkey Dance

partner. He was reared in a traditional Caddo family

and honored the ways of his people for all his life.

He was one of the founding members of the Caddo Culture

Club, organized in 1990 to involve youths in cultural

activities and ensure that traditional songs and dances

continue to pass from generation to generation. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

Vernon Hunter, Chairman 1997. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

Mary Louise Downing Davis, Vice-Chairwoman

2000. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Joyce Hendrix Hinse, Council Secretary

2000. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

In 1993, Clara Brown remembered taking

lunch to her husband when he was one of the group of

men who built the Caddo Community House. She said that

in the 1930s men used to sit under trees at Fritz Hendrix's

place and sing songs everyday. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

The Fritz Hendrix Memorial building

is the Caddo Senior Citizens Center. Photo by Cecile

Carter.

|

Culture Center and Museum, Caddo

Nation Complex. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Women circle the arena in the first

phase of the Turkey Dance. Photo by Dayna Lee.

|

During the third phase of the Turkey

Dance the women gather around the drumming men and sing.

Photo by Dayna Lee.

|

Murrow Dance Grounds in the off season.

The annual Murrow Dance is hosted by descendants of

Chief Whitebread and his wife through their daughter

Ellen, and her husband, Ralph Murrow. Photo by Steve

Black.

|

Caddo Dances always begin with the

Women's Turkey Dance, Nu ka oshun. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

|

The Flag Song is sung while the American flag raised

on a pole beside the dance ground is lowered. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

Specially designed medals were presented

to Caddo veterans honored in 2003 by a dance hosted

by Pete Whitebead, recipient of a Purple Heart for his

service in the Viet Nam War. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Singer and drummers lead the Drum

Dance, first of the evening dances. Those who know them

join in singing the Drum Dance songs bonding them with

the Old People, Ancestors, Kee-o-nah wah'-wah ha-e-may'-chee.

May 2, 2003. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Everyone follows the lead singers and drummers.

Photo by Cecile Carter. |

|

Whatever the U.S. government's motives were

for breaking tribally held land into individually held allotments—land

greedy interests (as seems transparent) or humanitarian ideals

(as claimed)—the action was an affront to the inherent

right of Caddo people to live and be governed as they wished.

Tending small gardens for the family and coming together to

plant large fields for the benefit of all was their age-old

way of life. Ancient ceremonies and celebrations gave expression

to their deep-seated spiritual beliefs. Forced moves from

homelands and a harsh environment in Indian Territory interrupted

Caddo self-sufficiency, but the constancy of their traditional

leadership was never doubted by Caddo people.

In the twentieth century, though, they were

painfully aware that the United States did not recognize the

Caddo form of government as legitimate. The President, Congress,

Secretary of Interior and lesser Washington officials were

deaf to the voices of Caddo leaders. The time had come for

the old Caddo way of governance to be "thrown away"

and a new way brought about.

Two Congressional Acts, the Indian Reorganization

Act (1934) and the follow up Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act (1936)

reversed U.S. policy favoring Indian assimilation. The first

recognized the right of self-determination for Native Americans,

authorized limited self-government under constitutions approved

by the Secretary of the Interior, and allowed the formation

of corporations to manage resources. Oklahoma was exempted

from the Indian Reorganization Act but the Oklahoma Indian

Welfare Act amended the Indian Reorganization Act to provide

for the organization on Indian tribes State of Oklahoma.

These federal laws cleared the path that led

the Caddo to organize a new form of government and receive

recognition as a sovereign nation with inherent right to self-government.

On the 17th day of the new year of 1938, surviving adult members

of the old Caddo Nation's three branches—Caddo, Hasinai,Natchitoches—voted

to accept Constitution and By-laws of the Caddo Indian Tribe

of Oklahoma. The vote was 314 for, 38 against. Ten months

later the Secretary of the Interior issued a Charter of incorporation

to the Caddo Tribe of Oklahoma. The Charter spelled out the

limits of tribal functions within the federal system as well

as safeguarding Caddo power: "To promote in any way the

general welfare. To advance the standard of living of the

Tribe through development of tribal resources, the acquisition

of new tribal land, the preservation of existing land holdings,

the better utilization of land and the development of a credit

program for the Tribe."

It was not easy for Caddos to become accustomed

to electing leaders. And it was not easy for those elected

to blend the role of Caddi with that of Chairman, nit-tso-sah-dos-cha-ah,

"one who takes the chair." The uppermost concern

of a Caddi often centered on cultural tradition. More and

more the responsibilities of Chairman became much like those

of a CEO for any corporate business. By mid-1990, tribal affairs

entailed complicated legal and business matters that required

expertise two hundred years advanced from the knowledge and

experience that made caddis powerful in earlier times. The

original Constitution and By-laws was amended and, in 1976,

revised and rewritten to better serve the best interest of

the Caddo Indian Tribe.

LaRue Martin Parker elected Chairman in 1999

and re-elected in 2001, is not the first woman to take responsibility

for directing the welfare of the Caddo Nation. She is, however,

the first to preside over an all female Council who have been

known to call themselves as the "Caddo grandmothers."

The next major constitutional change came with the adoption

of four amendments in 2002. The organizational name, Caddo

Indian Tribe of Oklahoma was officially changed to The Caddo

Nation of Oklahoma; blood quanta eligibility for membership

was reduced from at least one-eighth to at least one-sixteenth;

the period for terms in office for council members was increased

from two to four years.

The old Community House, built on five acres

deeded to the Caddo Indian Tribe of Oklahoma by Fritz Hendrix

and his wife Eva Longhorn Hendrix in 1940, was the center

of activities for many years. Hendrix was a son of Caddo Jake

and a leader of importance during the transition between traditional

leadership and constitutional government. Identified as Chairman

of the Business Committee, he signed the certificate of Corporate

Charter in 1938. The land from his allotment was deeded "in

consideration of the construction and maintenance of community

project.

Shaded by large, old, oak trees, next to the

Dance Ground, the Community House is still a center for Caddo

family gatherings and tribal functions. Downhill, the present

Caddo Tribal Complex has grown steadily since the first modern

building was dedicated to the memory of Fritz Hendrix. The

building first housed tribal offices and is now the Senior

Citizens Center. Next door is the Culture Center containing

Historic Preservation offices, a large indoor dance arena.

The Tribal Heritage Museum was more recently built next door.

A much larger building now houses administration offices.

The old dance ground on the hill above modern

buildings within the Tribal Complex is vibrant with color

and sound during warm months of the year. There is no set

calendar for these Caddo Dances—they are announced in

the old way. Someone will say, I'm going to give a dance on

such-and-such day, and the people come. Beginning in late

spring, fresh willow branches are cut and laid on top the

arbor frame that outlines the dance circle. The ground inside

the circle is swept clean. Grass surrounding the circle outside

the arbor is cut and cleared of winter debris. The old Murrow

Dance Ground is meticulously groomed for the annual dance

hosted by descendants of Chief Whitebread, his wife, their

daughter Ellen and her husband Ralph Murrow. Many families

camp under arbors, in tents, trailers, or RVs for two or three

nights of dancing.

Dancing always begins with the women's Turkey

Dance, Nu ka oshun. It starts in the afternoon, whenever tree

shadows begin to shade the circle. The drum is set in the

middle of the dance circle and the singers beat the rhythm

of the first song, "Come on Turkeys!" Women and

girls hearing the call enter the dance circle from all directions.

Caddo girls are taught from an early age, "You're Caddo,

you are one of us, you need to Turkey Dance." Turkey

Dance is a celebration—celebration of the survival of

the Caddo Nation.

When all are gathered, dancing with steps balanced

on the ball of their feet, a song urges, "Kick, Kick

the dirt!" The songs relate Caddo history—telling

about enemy encounters, victories won, and major events such

as the overnight formation of Caddo Lake. The songs are so

old that no one knows when they were first danced.

There are various stories about the origin of the Turkey Dance.

The most commonly told is that a hunter was in the woods when

he heard beautiful songs. Following the sounds he discovered

a group of turkey hens dancing around a gobbler. He watched

long enough to fix the dance in his memory and returned home

to tell all about it. After that, the dance he described was

used with songs composed to record the people's history.

Spanish missionaries in the 1700s described

Hasinai women performing a dance to celebrate the return of

warriors. Today, women and girls select a male partner to

welcome into the circle for the final stage of Turkey Dance.

The entire cycle of songs is seldom sung. Some songs have

been discarded over the years. Others have been and may still

be added. Even a shortened version lasts an hour or more,

and it must be finished before sundown. Remember, that's when

turkeys go to roost for the night.

The American flag raised on a pole beside the

dance ground is lowered at the end of Turkey Dance. The Flag

Song accompanies the ceremony. Composed at the beginning of

World War II, the words are:

Wunti shiahtsi ka kin ha nah

All the boys that means them

Kwi ahii sah dawi yasah

Where he was over there

Ki ah huu nit nah da gah

He came back now is among them.

Pete Whitebead, who served two tours in Viet

Nam and was awarded a Purple Heart medal, gave a dance to

honor Caddo veterans in June of 2003. After the Flag was lowered

that day, he carried it back to its owner, the widow of another

Viet Nam soldier. On Whitebead's request, the Department of

Defense sent special medals made for presentation to honored

veterans later in the evening.

Dinner for everyone is served following Turkey

Dance and the lowering of the Flag. Plates are served in the

Community House and carried to seats under the arbor. The

first dance of the evening is the Drum Dance. For Drum Dance,

the drum carried clockwise around the circle in harmony with

earth's rotation. The leaders are men, singers and drummers.

Young boys are encouraged to learn the songs by joining the

lead singers, but they are not allowed to beat the drum. Everyone

else falls in behind.

Songs are sung starting from the west side and

between brief stops at the points, north, east, and south.

The songs relate to the beginning of Caddo people on earth;

coming up from the old world of darkness into the new world

of light where they now live. For the last segment, the drum

is carried to the middle of the dance ground and the drummers

rotate in the center while the dancers move around them in

the direction of the earth.

Turkey Dance and Drum Dance are the heart of

Caddo culture. Both have significance in the preservation

or language, thought, and the spirit of Caddos past and present.

The dances that follow, Duck Dance, Bear Dance, Swing Dance,

Stirrup Dance and a string of others are light hearted fun.

The songs of one of the last dances, the Bell Dance, are the

most beautiful and may be the oldest. There is no drum, only

the ring of bells in the hand of the leader. Tony Williams

was reared in a traditional Caddo family and honored the ways

of his people for all his life. He was one of the founding

members of the Caddo Culture Club, organized in 1990 to involve

youths in cultural activities and ensure that traditional

song and dance continues to pass from generation to generation.

|

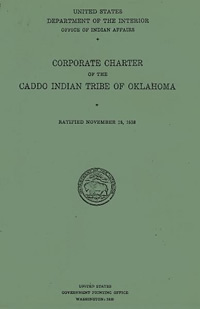

In 1938 the Secretary of the Interior

issued a Charter of incorporation to the Caddo Tribe

of Oklahoma. The Charter spelled out the limits of tribal

functions within the federal system as well as safeguarding

Caddo power: "To promote in any way the general

welfare. To advance the standard of living of the Tribe

through development of tribal resources, the acquisition

of new tribal land, the preservation of existing land

holdings, the better utilization of land and the development

of a credit program for the Tribe."

|

Frequently asked

Questions Regarding the Caddo Indian Nation

Who is a Caddo?

A Caddo person is defined by the Constitution and

By-laws of the Caddo Nation...

read

more>>

|

Noah Frank, Chairman 1995. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

LaRue Martin Parker, Caddo Tribal

Chairman 1999-. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Frances Cussen Kodaseet, Council

Representative 2000. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Working Council, August, 2003. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

The old Community House has been

a center for Caddo activities since sometime around

1938. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Culture Center, Caddo Nation Complex.

Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Administration Building, Caddo Nation

Complex. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Dance ground at the Caddo Nation

Complex. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Women wearing traditional dance costumes

enter the dance arena at the start of the Turkey Dance.

The woman on the left, Frances Cussen Kodaseet, carries

a leadership cane believed to have been presented to

the Caddo by the Spanish prior to 1809. Photo by Dayna

Lee.

|

Second phase of the Turkey Dance.

Photo by Dayna Lee.

|

Caddos enjoy congeniality in camping

during dances held on the dance ground at the Tribal

Complex and the annual dance held at the oldest dance

ground still in use, the Murrow Dance Ground. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

The 86th Annual Murrow Dance was

held June 27-29, 2002. Photo by Steve Black.

|

Youngster playing near drum at Murrow

Dance Ground. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Pete Whitebead returns the folded American flag to the

widow of a Caddo warrior who permitted her husband's flag

to be raised for a dance honoring veterans in 2003. Photo

by Cecile Carter. |

Back of special Caddo veterans medal.

Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

Young boys are encouraged to learn

Drum Dance songs by joining the lead singers, but they

are not allowed to beat the drum. May 2, 2003. Photo

by Cecile Carter.

|

Even the youngest feels the beat of the drum. Photo by

Cecile Carter. |

|