|

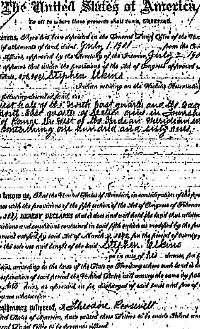

To his excellency, The President of the United States,

Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C.

February, 3 1888

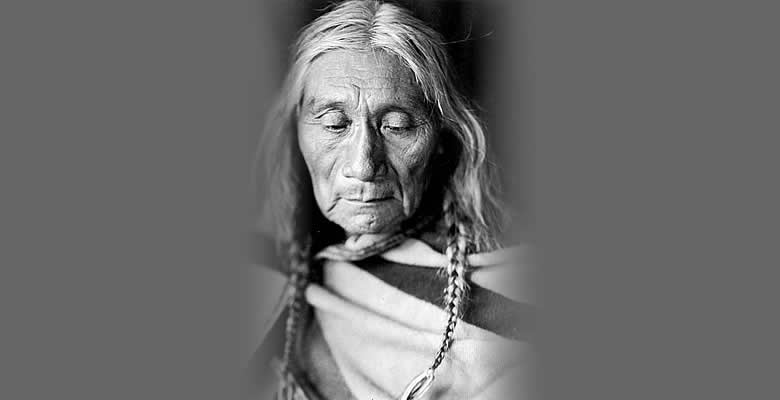

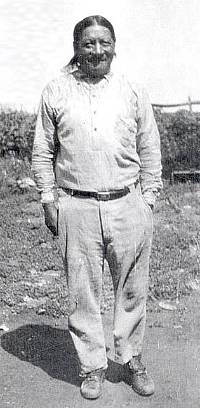

Whitebread, a chief of the Caddo tribe of Indians would

say to his great Father that, at the request of his people,

he has come a long journey to see him and ask him to listen

for a little while that he may learn the wants and wishes

of his children who are so far away.

Whitebread knows that the great Father has so many people,

whose interests he must care for, that only a little while

can be spared to hear him. Therefore he will speak but few

words and as directly as he can.

Last winter one of his old men, a chief of his tribe was

here, and told the Commissioner of Indians affairs that his

people were not prepared for, and did not wish their lands

to be allotted to them. There were many reasons for this.

First because they had no country that they could call their

own—that where they now live was by the sufferance of

the great Father's government, growing out of an agreement

which his people, and the people with whom he now lives (the

Wichitas and other bands) has never authorized to be made,

and which had never been ratified by the government of the

U.S. or by the affiliated bands. Second, because his people,

when they had a country of their own, lived mostly by hunting

and cultivating small patches of ground, and were used to

moving from place to place in the spring and summer where

the grass was good, and the streams were running with clear

water, and in winter where they could find shelter from the

storms and wood to make fires. Such had been the custom of

their fathers and fore-fathers farther back than their tradition

went, and which they had inherited for so many generations

that it had become a part of their nature, and it was hard

to get rid of.

Their old men and the present generation had this way

of living in their hearts. They now know that the game is

disappearing, the buffalos are all gone, and the elk is no

longer seen in their ancient hunting grounds, and the deer

and antelope, in their country almost extinct, and his people

feel that they must as fast as they can, take up and follow

the course of the white man. The old men are preparing for

this and are trying as well as their untutored ways will allow,

to teach their children in this way. His people believe that

the great Father and his people desire to aid them in this

and to promote their happiness and make them good people.

But he would remind his great Father that the ignorant red

children of the plains and mountains are like little infants

and that it requires much patience and care to teach them

to crawl and walk, and advance by slow degrees to maturity.

He believes that before his generation dies out this good

end may be attained, but it is only to be reached by patient

effort. Where ever their homes have been their country has

been enjoyed in common. If one place failed in grass or water,

or did not give sufficient protection they could hunt another

without hindrance. If confined to one spot, and the soil were

unproductive and their corn and vines withered from the drought

and the water dried up they could hunt a better place.

Besides these things they are ignorant of the use of many

things easy to the white man. They know that a few farmers

and black-smiths and carpenters and mill-wrights are sent

to teach them, but how can two or three or even a dozen farmers

and one or two other mechanics of each class teach, or attend

the wants of several thousand people widely scattered over

a territory many miles in width and length, and among a people

with but few of the implements and tools necessary, and where

there are not many gentle oxen and horses for use.

We beg to assure our great Father what we are doing out

best, we are trying to teach our young men and children the

way of the white man, and we believe if not too much hurried

that in a few years we will be able to make our own selections,

if we have granted to us a country of our own, where we can

build on our cabins, clear our grounds, make our homes and

raise our children. Then we will be glad to say to our Father

your children have traveled the white man's road a while,

he finds it good, and we want you to allot to us our home.

My people have instructed me to say to you that they hope

you will set aside the order designating the Caddos and affiliated

bands as tribes when allotments should be made.

|