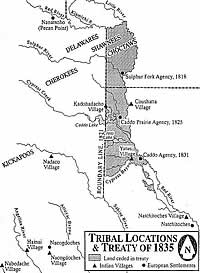

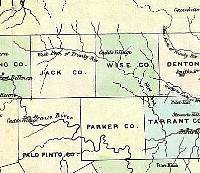

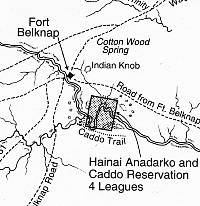

Tribal Locations and Treaty of 1835,

From The Caddo Indians: Tribes at the Convergence

of Empires, 1542-1854, F. Todd Smith, 1995, courtesy

of the author.

Click images to enlarge

|

|

Some Caddo voices are quiet like a whisper.

Some ring out like a bell calling workers in from the field.

Some say, "Those people who said those things, they did not

know." Some say, "those people who said those things—maybe

they were true—maybe not. does not seem right."

Caddo lands in Louisiana

were ceded by treaty between the Caddo and the United States

in 1835. The treaty required the Caddos to leave the boundaries

of the United States within a year. At that time Caddos were

living on the west end of a lake they called T'soto, later

known as Caddo Lake. Their name for the place was Sha'chahdíinni,

"Timber

Hill." On leaving Sha'chahdíinni, the Red

River Caddos of Louisiana were twenty years without a home.

Texas seemed a safe place for Caddos to resettle,

build new homes, plant new crops, and nurture children. East

Texas was the ancestral homeland of their kindred, the Hasinai

("Our People"). Generation after generation of Caddos

wore major footpaths through the east Texas black land prairie

on their way to hunt, camp, meet and trade. An east-west path

led to favored camp sites in present Tarrant County. A north-south

trail, the Caddo Trace, crossed the northeast corner of what

is now Dallas County. There were no roads. North central Texas

still belonged to Indians when Principal Caddo chief, Tarshar,

led approximately three quarters of the Caddos to the western

fringe of Hasinai traditional hunting ground in 1836.

|

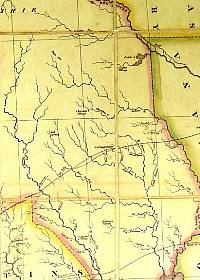

East Texas as depicted on Stephen

F. Austin's 1830 map. Texas seemed a safe place for

Caddos to resettle (in 1835), build new homes, plant

new crops, and nurture children. East Texas was the

ancestral homeland of their kindred, the Hasinai ("Our

People").

|

|

|

| |

Estimated Population of Texas in

1836

Estimated Population of Texas in September,

1836:

Anglo-Americans 30,000

Mexicans 3,470

Indians 14,200

to which add the civilized tribes—Cherokees, Kickapoos,

Choctaws, Chickasaws, Potawatamies, Delawares, and Shawnees—8,000

Morfit to Forsyth, August 27, 1836

|

|

|

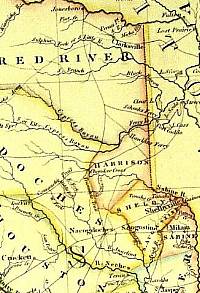

1841 Arrowsmith map of Texas showing

east Texas. Notice the trails through Nacogdoches. Trammel's

Trail leading north is part of the old north-south Caddo

Trace, now being used by Anglo settlers pushing into

Texas from Arkansas. Click to see enlarged view and

overview of map.

|

|

Hasinai villages, like

Caddo communities, suffered a great loss of place and population

before 1835. Immigrant Indian bands as well as white people

crowded into the east Texas territory once dominated by Hasinai.

Only Hainai and Nadako, two of the old Hasinai locations,

remained in 1835. Written documents from this time forward

refer to the people of those villages as "Ioni"

and "Anadarko".

When Sam Houston became

President of the Republic of Texas, he sent commissioners

to make a treaty with the Hainai and Nadako. A resolution

"that the Senate advise and consent to ratification of

a treaty entered into between T J Rusk and K H Douglass on

the Part of the Republic of Texas and the Chiefs of the Ioni

and Anadarko Tribes of indians on the 21 day of August 1837"

was submitted to the Texas Senate in October, 1837. The treaty

was lost at some unknown time. Not even a copy can be found

in the great volume of Texas Indian Affairs records, correspondence,

and treaties that are carefully preserved from early days

of the Revolution to present.

|

|

|

| |

Grandmother's story:

well, the way grandmother's sister,

she's the one who really told some of the stories about that.

She was much older than my grandma was. She must of been about

eight or ten years older than my grandmother was. . . . And

my grandmother, her mother, they put her on a horse with my

grandmother and her sister. . . .her mother turned around

to go back cause she knew that the way things was going turning

out they was going to starve to death or die or somebody seeing

dying on the way. That she wanted to go back to Louisiana,

if she was going to die she wanted to die back home. And she

kinda rebelled against em, and she was killed. My aunt said

that soldiers stuck her with a knife. Is what she said. She

was on this horse and she said her mother fell off the horse.

She was telling about that's when they moved.

Fallis Elkins, 1973

|

|

|

| |

Conflict

Treaties did not prevent whites from taking

Indian land in east Texas. Surveyors swarmed valleys of the

Neches and Angelina streams where the Hasinai had lived for

centuries. New white settlers surrounded the Anadarko and

Hainai villages and pressed against the settlements of other

Indians who had emigrated and settled there first. Caddos

quickly learned; whenever men with sticks and chains appeared,

white settlers soon followed. Conflict was inevitable. Hainais

and Anadarkos fled from violence, moving west to the Three

Forks of the Trinity River where Caddos kindred from Louisiana

were trying to establish new homes.

|

|

|

| |

"Mistaken for renegades":

There was so many different communities

that the word "nah" . . . denoting "from"

"those" "they" "them" "of"

. . . Nah-shu-tush "It's a community that they lived

in . . .I think there were about seven bands altogether .

. . . the Ha-si-nai, Ka-doha-da-cho, Hai-Nai- Hai-ish, Ya-ta-si,

they were often mistaken for the renegades of other tribes

. . . . several were—as I say, mistaken for renegades

when they were out hunting, that's where most of the murders

were committed . . . .

Sadie Bedoka Weller, 1968.

|

|

|

Detail from 1841 Arrowsmith map in

Robertson County reads "Caddo Village burned by

Genl Rusk 1839"

|

|

Caddos crossing from Louisiana into Texas roused

suspicion and animosity. Texas Declaration of Independence

was only month's old. Many Anglo Americans greedy for free

land in Texas brought anti-Indian sentiments with them. Almost

all were gripped by fear that Caddos from Louisiana intended

to lead massive attacks plotted by Mexicans. Tarshar and other

Caddo chiefs admitted that Mexican agents had been among their

people but denied that the Mexicans were given Caddo loyalty.

Still rumors were rampant. Caddos were accused of instigating

or joining in frontier attacks made by roving groups of plains

Indians.

Texans petitioned United States officials to

keep Caddos in Louisiana, at least until the war was over.

General Thomas J. Rusk went a step farther in November 1838.

Riding at the head of seventy men he invaded the United States

to take control of Caddos living well inside Louisiana, about

twelve miles from Shreveport. The Caddos were disarmed, their

meager arsenal deposited with their agent in Shreveport. Rusk

demanded they stay there until the war with Caddos on the

Texas frontier ended. After making this "treaty"

with the Caddos in Shreveport, Rusk joined a campaign against

Caddos on the Trinity River. He found and burned their village

in the Cross Timbers west of the Trinity in January 1839.

Texas Rangers, mostly local community volunteers

organized to protect the frontier from Indians, became progressively

diligent in their search for and destruction of Caddo villages.

Accounts of Indian fights are many and various. Told and retold,

some like the "Battle of Village Creek", have become

part of Texas folklore. The report written by Acting Brigade

Inspector Wlliam N. Porter on June 5, 1841, may be an accurate

account of the running battle that took place May 24, 1841.

|

A grass-thatched Caddo-style house

blazing less than a minute after the fire was set. The

scene eerily recreates the cold day in January, 1839

when General Thomas J. Rusk torched a Caddo village,

not long after making a "treaty" with the

Caddos. Photo by Velicia R. Bergstrom.

|

Within five minutes the house collapses.

Five minutes between home and embers. Photo by Velicia

R. Bergstrom.

|

|

|

| |

Battle of Village Creek:

We soon found two villages, which we found to be deserted-the

Indians at some previous time, had cultivated corn at these

villages. There were some sixty or seventy lodges in these

two villages. They were on the main branch of the Trinity.

. . . General Tarrant deemed it imprudent to burn these villages,

for fear of giving alarm to the Indians. . . but they were,

in a great measure, destroyed with our axes. . . . On the

24th . . . . we found very fresh signs of Indians—The

spies were sent ahead, and returned and reported the Indian

Villages in three miles. We arrived in 3 or 4 hundred miles

yards, and took up a position behind a thicket. . . . the

line was formed, and the word given to charge into the Village

on horseback; and it was taken in an instant, the Indians

scarcely having time to leave their lodges before we were

in the Village; several were shot in attempting to make their

escape. Discovering a larger trail leading down the creek,

and some of the Indians having gone in that direction, a few

men were left at that Village and the rest at full speed took

their course down the creek, upon which the Village was situated.

Two miles from the first Village,

we burst suddenly upon another Village, this was taken like

the first—There was another in sight below—many

of the houses having fusiles, the men race toward this Village

on foot; but the Indians having heard the firing at the second

Village, had time to take off their Guns and ammunitions,

and commenced occasionally to return our fire. From this time

there was no distinction of Villages, but one continued Village

for the distance of one Mile and a half, only seperated [sic]

by the creek upon which it was situated.

We had now become so scattered—Genl.

Tarrant deemed it advisable to establish some rallying point

to which smaller parties should be expected to rally—We

marched back to the second Village, . . .General chose this

as the position—From this point Capt Jno. B. Denton,

aid to Genl. Tarrant, and Capt. Bourland took each ten men

for the purpose of scouring the woods. The parties went different

directions, but formed a junction one mile and a half below

the said Village . . .discovering a very large trail—much

larger than any we had seen, . . . perceiving though the timber

what appeared to be a village still more large than any they

had heretofore seen, but just as the head of the two detachments

were on the end of entering the creek, they were fired on

from every direction by an enemy that could not be seen. .

. . In this situation the men did the best they could . .

. making every demonstration, as though they intended to charge

the creek. The Indian yells and firing soon ceased, and both

parties left the ground. It was not the wish of General Tarrant

to take away Prisoners. The women and children, except one,

escaped as they wished, and the men neither asked, gave, or

received any quarter.

From the Prisoners who we had taken,

we learned that at these Villages there were upwards of one

thousand warriors, not more than half of whom were then at

home, the other half were hunting Buffalo, and stealing on

the Frontier.

William N. Porter, Acting

Brigade Inspector, "Report of the Brig. General Tarrant's

Expedition against the Indians on the Trinity"

Original in Texas State

Archives, Austin

|

|

|

Jose Maria, Caddo name Iesh, was

the leader of the Caddos, Hainais, and Anadarkos in

Texas. He was esteemed by both white men and Indians.

This sculpted bust of Iesh stands in the National Hall

of Fame for Famous American Indians, Anadarko, Oklahoma

|

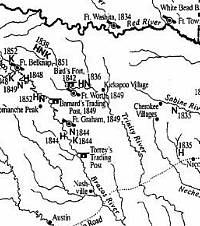

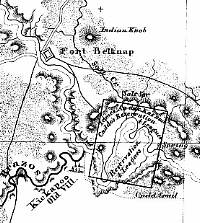

Caddo Tribal Locations 1835-1854,

From The Caddo Indians: Tribes at the Convergence

of Empires, 1542-1854, F. Todd Smith, 1995, courtesy

of the author.

|

|

According to Porter, who was there when the

battle was fought, General Edward H. Tarrant organized a company

of 67or 69 volunteers who left Fort Johnson (an small fort

in present Grayson County). Five days later they found two

deserted villages on the western branch of the Trinity River.

After another five days they found the first of four occupied

villages, about two miles or less from another. They charged

the first on horseback and took it easily. The second was

taken just as easily. Indians in the third village, though,

heard the gunfire from the second and fled. The fourth village,

larger than the others, was seen only through the trees. The

Indians there had time to prepare. As Tarrant's men came near,

they were met with gunfire coming from every direction. One

Texan was killed, two wounded. Convinced they were outnumbered,

they picked up their bounty from the first three villages

and headed back to the white settlements.

A count of twelve dead Indians was claimed by

the Texans but, because of the great amount of blood seen

on their trails, they thought more were killed or wounded.

Not counting the fourth village seen only through the trees,

Porter reported 225 lodges and about 300 acres of corn in

the villages.

When a larger force of Texans returned in July,

they found the villages empty and burned the dwellings. Caddos,

Hainais, and Anadarkos had lived there, along the present

Fort Worth/Arlington boundary. With them were fragmentary

groups of Cherokees, Creeks, Seminoles, Wacos, and Kickapoos.

Later that summer, Bird's Fort was built near the battle site.

It was occupied for only a few months but remained in use

as a frontier gathering place.

The Caddo chief who led Caddos into Texas, was

killed in early 1840. His name is spelled Tarshar in most

documents of the period, but is given as "Wolf"

in some. Since the Caddo name for wolf is ta'-sha, that is

probably the correct name of the Caddo chief. After Ta'-sha's/Tarshar's

death, José Maria rose to be the principal leader of

the Caddos, Hainais, and Anadarkos. Esteemed by both white

men and Indians, he gained an almost legendary status during

the turbulent years that followed.

Let Us Live Together in Peace: Councils, Treaties, and Promise

of Peace 1843-1846

The unwavering desire of Caddos, Hainais, and

Anadarkos was to have a peaceful, permanent, place to call

home. Without hesitation, they attended peace councils, signed

treaties, and staunchly kept the terms. Principal chief José

Maria and Caddo chiefs Bintah, Chowa and Ha-da-bah met with

Commissioners for the Republic of Texas in March 1843. The

meeting was on Tehaucana Creek at a placed used for intertribal

councils long before Americans arrived in Texas. Chiefs and

headmen of the Delaware, Shawnee, and the so called "wild"

tribes, Tawakoni, Waco, Wichita, and Keechi, were also represented

at the Council. The Commissioner appointed by President Sam

Houston addressed the Council:

|

Lillie Whitehorn, granddaughter of

Jose Maria 1978, had this to say about her grandfather:

"He's got a pretty name and I do not know why they

use that Jose Maria-I do not like it. They should use

his Indian name Caddi Ha-Iesh." 1973 photo by Cecile

Carter.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

The President of Texas has heard

that our brothers, the red men, want to make peace with us:

for this purpose he has sent us, his Commissioners to meet

you. . . .You have heard the talk of our President read to

you. He is the friend of the red man; he always has been their

friend: he does not talk to them with a forked tongue. He

tells you to listen to the words of the Commissioners. We

will not deceive you, or give you a crooked Talk.

General G. W. Terrell,

Commissioner in behalf of the Republic of Texas

|

|

|

| |

This "Talk" offered promises the "red

men" longed to see fulfilled: a country to live in, in

Texas; trading houses in their country; agents to live among

them and always send their talks to the President, carry his

talks back to them, and see that white people did not intrude

upon them. Indians could trade at Torrey's Trading House on

the Brazos River without being harmed by Texas citizens. They

could plant corn any place north of the Trading House that

was built near the mouth of Tehuacana Creek about four miles

from the old Council ground.

|

|

|

| |

Bintah, spoke for the Caddos saying:

. . . I have only one thought in my heart,

I have heard your talk and hold fast to it, your talk is good.

. . . What I say to day I shall say always. If I should awake

in the middle of the night, I still think the same as now,

and I will be true all the time. Our women and children will

now be without fear, the road is cleared, for them to travel

without danger, I believe that what you have told me is truth,

and that from this time henceforth we are all friends----"

|

|

|

President Houston's certificates

recognizing Bintah & José Maria.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Following the council at Tehaucana Creek, Bintah

and José Maria were invited to visit President Sam

Houston at the Texas Capital. Eighty-five years later, the

widow of another Caddo Chief, Whitebread, turned two carefully

preserved documents over to the tribal attorney. (The documents

are archived in the Oklahoma Museum of History.) Except for

the names, Bintah chief of the Caddo and José Maria

chief of the Anadarko, they were identical. The great seal

of the Republic of Texas was set on white, blue, and green

ribbons that Houston said denoted peace, the sky, the grass

and trees, existing as long as the world stands.

Treaty at Bird's Fort 1843

A Grand Council to conclude a "Treaty of

Peace and Friendship" was scheduled to meet August 10,

1843 at Bird's Fort. President Houston was present on the

set date. He waited a disappointing month for the Comanches

to arrive before going back to the Texas capitol. The Comanches

never came but Commissioners and the chiefs of nine tribes--again

including Caddo, Anadarko, and Hainai, signed a treaty that

incorporated the principals of Houston's peace policy on September

29, 1843. Commissioners were careful not to include

recognition of the Indians rights to possess Texas land. The

Treaty at Bird's Fort is a rarity. It is one of the few treaties

ratified by the Republic of Texas Senate.

1844 Council

Although chiefs of nine tribes signed the Bird's

Fort Treaty, errant bands continued raiding and stealing horses.

When pursued, they frequently passed through the Anadarko,

Caddo and Hainai villages on trails that led from white settlements

to the villages of different Wichita bands. They were thoroughly

rebuked by Caddo chiefs at a council meeting on the Tawakoni

Creek grounds in 1844.

|

Bird's Fort Treaty Ratification Proclamation,

1843. The 1843 Treaty at Bird's Fort is one of the few

treaties ratified by the Republic of Texas Senate. Texas

State Library & Archives Commission Archives &

Manuscripts "Indian Relations."

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Caddo Chief Red Bear:

I do not like to see guns firing and blood

spilled, for I am a friend of peace. I am one of the oldest

of my tribe. All the red men and all of my other brothers

know me well: they know I want to travel on in the white road.

. . .my hands are clean and I like to see others the same.

. . .I live upon the Brazos. José Maria the Anadarko

chief is my neighbor, when our brothers steal horses and take

them through our towns the whites blame us for it. . . .

Caddo Chief Ha-de-bah:

. . .You have heard what the old chiefs

have said: I want you now to hear me, a young man speak. .

. .I want you to hold strong to their talk. We are not talking

here to children: our talk is strong and we all want you to

hear it. Your warriors by living as we would wish them to,

would be happy, and your wives and children see no danger.

Captains and you, young warriors, I want you all to stop going

to war: 'tis all I have to say to you.

José Maria seldom spoke in the

earlier councils. This time, while holding a string of wampum

beads, he took his turn saying:

As I am myself, small in size, my words

to fit me, shall be few. long talks admit of lies; my talk

shall be short but true. Captains and chiefs, listen to me.

The Great Spirit has given to us a good day, and we have listened

to many good talks. Captains I want you now to listen unto

me. the Big Spirit, above, is watching all now here. young

men you all look happy. Captains, if you love your children

advise them not bad, but good; and show to them the white

path. . . .The Great Spirit our father and our mother, the

earth sees and hears all we say in council. You have listened

to good talk. I hold the white path in my hands given to me

by our white brothers. look at it: see it is all fair. To

you, Waco and Tawakoni captains and warriors, I give it. stop

going to war with the white people. they, the white people,

gave it unto me: I give it now to you: use it as I have done

and your women, and children will be happy, and sleep free

of danger. I give to you this piece of tobacco to smoke, and

consider of the white path. when you return to your village,

then smoke this tobacco, think of my words and obey them.

|

|

|

| |

The straight talk of the chiefs had no lasting

effect on the young men of the Waco, Kichai, and Tawakoni.

By the Fall season, Red Bear felt it was time to take charge

and punish the culprits. He sent messengers to José

Maria's village to raise men for war against the Waco. The

warriors intended to go to the white settlements and ask the

Texans to join with them against the Wacos or, if they did not

want to fight, they would be asked to witness the punishment

of the Wacos. The messengers were persuaded to wait at José

Maria's village until the next council scheduled for October.

1844 Tehuacana Creek Treaty

President Houston was present at the next Council

held in October, the first attended by Comanches. A treaty

much like that made a Bird's Fort was concluded and presents

were distributed to all but the Wacos who were told they could

not receive theirs until they brought in the stolen horses.

Wild talk and rumors of whites' deceit began

to spread throughout the Indian villages. Perceiving a danger

in rising unrest caused José Maria to present the longest

talk ever recorded for him. Honoring his treaty commitment,

he reported to the Indian agents at Torrey's Trading house

in January 1845:

|

|

|

| |

My young men have left me and gone around

because they have heard bad talk, but I do not believe this

bad talk, and this is the reason I wish to hold council. That

my young men may be convinced that the talk they have heard

is false and the talk of bad men.

When I went out on my hunt, I got a passport

from the agent, and did not meet any trouble until I got nearly

back to this place. When I met this bad news.

When Col. Williams [an Indian agent]

went up into our country last summer, I was told that the

object of his mission was to get all the women and children

in to the council in the fall, and that the whites were then

to fall upon them and kill them. The waggons with the goods

were to stop below and the troops from the United States were

to assist in killing them. At the last Council all of the

Captains said the old men with grey beards would not tell

lies.--My beard is not yet grey: I am a young man, but I speak

truth. For myself I believe that these stories I have heard

are lies. . . .For my own part I am not afraid, but my people

say I am a fool for staying so near the whites, as so soon

as the corn gets fit to eat they intend to raise and kill

them all and that the reason these goods were put here was

to cheat our people out of their hunts to pay for the good

white men they have killed.

I have understood also that if we did not

go with the whites and help kill the Waco that the whites

would think we were friends to the Waco, and kill us.--The

Waco say that if we do not move out, away from the whites

they will steal our horses, so you see we are between two

fires. What shall we do? I know that it is the desire of the

whites to make peace with all, but it is impossible. The whites

have done their best to make peace, but the Waco and others

will not be friends.

Two nights ago news was brought me that

the Waco had stolen all the horses from 5 of my men, and that

the men had left their families and pursued the Waco, and

I have not heard of them since and do not know whether they

are killed or not.

The Waco also stole some horses from some

Lipan a short time since. . . .They have also stolen all the

horses from Bintah's son, and he has followed them. . . .I

come in to see you and give you my talk so that it can be

sent to your Chief as I do not wish to go around like my young

men have done but come straight to the white path, and pursue

it. Our women and children are naturally scary; but myself

and men are not afraid.

Brothers my talk is done.

Jose Maria

|

|

|

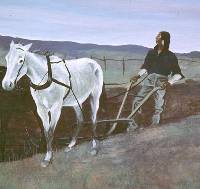

"José Maria and his people

had about 150 acres of some of the finest corn ever seen in

Texas. Their gardens were green with plump watermelons, beans,

peas, and pumpkins yellowed on vines." Photo by Frank

Schambach of Arkansas corn field.

|

José Maria and his people had about 150

acres of some of the finest corn ever seen in Texas. Their

gardens were green with plump watermelons, beans, peas, and

pumpkins yellowed on vines. In the general council held at

the Tehuacana Creek grounds that fall, he and Bintah spoke

once more of their hope that the white path would be kept.

Towaash, chief of the Hainai, told the council:

|

Pumpkins were one of the favorite crops of the Caddos. Photo

by Frank Schambach. |

|

| |

The President thinks now that all his people

are not afraid, . . . because his women and children know

that all is peace. Our women and children are not afraid now

of the white warriors, all is good. . . .I know what I promised

at the first Treaty, and I have done as I said. The President

then gave us powder and Lead, and told us to go home and shoot

deer and buffalo, and raise corn, for our women and children,

so that in the cold rainy weather they would not cry for bread

and meat. We have done so and found that it is good. All that

he told us was true, and now I can go home to my people and

tell them that all is still good, that they can eat and sleep

in safety and feel no more afraid.

|

|

|

| |

The Caddos who made the long journey from Louisiana

to Indian Territory had not endured conflicts with white men.

They were, however, as homeless in Indian Territory as their

kinsmen in Texas. Forced to depend almost entirely on hunting

to feed their families, they somehow managed to maintain dignity

while struggling to support their families in midst of conflicts

between immigrant tribes moved to the Territory by the treaties

with the United States and prairie tribes reluctant to give

up their historic hunting range.

The Creek Indian Nation attempted to bring peace

by hosting a intertribal council near the present town of

Eufaula, Oklahoma in 1845. Eight Caddo chiefs were among those

attending. Cherokee Indian Agent, Pierce M. Butler, noted

his impression of the Caddo spokesman, Chowawhana:

|

The Caddos who made the long journey from

Louisiana to Indian Territory followed the course of the Red

River. From Carter, 1995, Caddo Indians: Where We Come

From, courtesy of the author.

|

|

| |

The talk of the Caddo chief was of

deep interest. He was a striking man of great personal beauty

and commanding appearance. Small in stature, yet beautiful

and attractive features, dressed in what would be called Indian

magnificence, feathers, turbans, and silver bands. His speech

was looked for with interest and was very well received. Approving

the council, deploring the past and probable future fate of

the red man, had been gloomy, future prospects worse, hostility

among themselves, destruction of their race and ruin of their

children. His people honest and true to the objects of this

council. Would, when he got home assemble the people and tell

them the talk. The same as though they were present. . . .Creek

chiefs made long speeches in good taste and temper promising

peace and good will to the effect that their brothers the

Caddos had agreed to become the messengers of this tobacco

and beads to the Comanches and the Osages to take it to the

Pawnee Mohaws wish them to spread the news wherever they went.

notes taken at the "Grand

Council" by Cherokee Agent Pierce M. Butler

|

|

|

In 1846 the Lone Star flag of the Republic

was lowered and the flag of the United States raised in State

of Texas.

|

Texas Statehood and US Treaties

Peaceful relations between tribes and Texans

were still tenuous when Texas was annexed to the United States

in 1846. As a state, Texas reserved rights to all public lands,

assumed no further responsibility for Indians, and charged

the federal government with the right and duty to defend the

state's frontiers. In other words, the United States had political

control of the Indians, but the state controlled the land

they lived on.

The United States lost no time in negotiating

a treaty with the Texas Indians. The circumstances were odd.

Indian signatures (marks by their name) were collected on

a separate sheet of paper but were not identified by tribe

and the treaty between "commissioners on the part of

the United States" and the "undersigned chiefs,

counsellors and warriors of the Comanche, I-on-i, Ana-da-ca,

Cadoe, Lepan, Long-wha, Keechy, Tah-wa-carro, Wi-chita, and

Wacoe tribes of Indians, and their associate bands" was

actually not written until after the commissioner returned

to Washington D.C.

|

1846 United States Flag (28 stars).

|

|

| |

KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS that Jose

Maria a chief of the Ano-ddah-kos and the tribe to which he

belongs are by Treaty, on terms of Peace and Friendship with

the United States of American.

Jose Maria has in person visited Washington

City, the seat of Government of the United States and conducted

himself according to the terms of the treaty to which he was

a party.

This paper is given in testimony

of the Friendship existing between the two countries.

Done at the City of Washington this

twenty fifth day of July one thousand eight hundred and forty

six

|

|

|

Major Robert S. Neighbors, special agent

for the Indians of Texas, was a loyal and courageous friend

and protector of Caddo rights and safety. From Walter Prescott

Webb, 1935, The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense.

|

Following the signing of the 1846 treaty, a

delegation of the chiefs was taken to Washington D. C. Major

Robert S. Neighbors, newly appointed special agent for the

Indians of Texas accompanied them. The long and tiring trip

was meant to impress the Indian leaders with living conditions

in the United States and the power of its government. As a

bonus, Major Neighbors gave the chiefs the horses they rode,

on arrival back in Texas. José Maria brought home a

document signed by President James L. Polk that was proudly

protected through several generations.

The Bitter Years 1847-1853

The Anadarko village was then sixteen miles

west of the present town of Hillsboro. A second Anadarko-Hainai

village was not far off away. José Maria had formed

friendships with good Texas families all along the Brazos

River and often visited their homes. Another kind of Texan,

a troublemaker with a bad reputation, accused José's

people of stealing hogs and threatened him with a gun. He

then tried to raise a force to kill José Maria's entire

band. White friends told the chief it would be wise to move.

So Anadarkos once more left homes and fields behind, moving

to a place on the Navasota River in Limestone County.

It was not their last forced move. Two years

later the Anadarko, Caddo, and Hainai were living in Palo

Pinto County. Surveyors were seen all about and they had learned,

wherever there were men with measuring sticks and chains,

settlers soon followed.

In 1848, Texas Rangers killed a sixteen-year-old

nephew of Caddo chief Ha-de-bah. They had no excuse for doing

so. They knew the young man. He had supplied their post with

game and gave them no cause to kill him. José Maria

had a hard time controlling his people's anger but managed

to convince them they should keep the treaty and let the agent

handle justice. Major Neighbors recommended yet another move.

José Maria again relocated his people. This time farther

northwest near a well known landmark called Comanche peak.

A Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs

in 1849 said that José Maria was the leader of twelve

hundred people. Caddos who had gone to Mexico after leaving

Louisiana had returned during the summer of 1844 and fragments

of some other tribes had joined under José Maria's

leadership. The report also stated that the Anadarko and Hainai

as well as the Caddo had migrated from Louisiana. Texans in

1849 commonly chose to forget, or did not know, that the Anadarko

and Hainai had lived in northeast Texas for hundreds upon

hundreds of years before Americans arrived. Major Neighbors'

census recorded 1,400 Caddos, Hainai, and Anadarkos with 280

warriors.

Forced to abandoned field after field, often

before they could harvest crops, Anadarkos & Hainais living

near Comanche Peak made only enough corn to last about 4 months

in 1853. Caddos near the junction of Clear Fork with Salt

Fork on the Brazos made so little corn it was consumed in

roasting ears. The Caddo Chief was dead. Some of the young

men had taken to whiskey. Game was scarce for all. The treaties

signed in good faith and earnestly kept had failed to relieve

their uncertain lives.

End and Beginning of Homelessness 1854-1859

Early in 1854, the Texas legislature reacted

to pressure by citizens demanding a protective line between

themselves and the Indians. An act providing for Indian reserves

gave the federal government authority to select twelve leagues

of land for the reservations. A line of military posts was

intended to separate Indian range from white settlements.

Captain Randolph B. Marcy and Major Neighbors were appointed

to locate and survey lands. They called the chiefs together

for a council.

José Maria was now sixty years old. He

had attended too many councils with too many white men to

have faith that this one would have truer meaning than the

others. In this council his words reflected many crushed hopes.

|

"It is believed that there is no chief

on the frontier of Texas, when friendship is of most importance

and value than Jose Maria--nor any to deserving more consideration,

or is better entitled to good treatment than he." Jesse

Stem, US Special Indian Agent for the Indians of Texas 1852

|

Area where Caddo villages stood during the "bitter years

1847-1853." The map was published in 1857, but the two

Caddo village locations shown are those prior to 1854. Galveston,

Houston, and Henderson Railroad map. Courtesy David Rumsey Map

Collection. |

In 1848, Texas Rangers killed a sixteen-year-old

nephew of Caddo chief Ha-de-bah. They had no excuse for doing

so. They knew the young man. He had supplied their post with

game and gave them no cause to kill him. Drawing from Walter

Prescott Webb, 1935, Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier

Defense.

|

The sandy, salty, and intermittent Salt

(or Main) Fork of the Brazos not far above its confluence

with the deep Clear Fork. Caddos lived very near here in the

early 1850s in great uncertainty. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Captain Randolf Barnes Marcy located and mapped the lands

that became the Brazos Reservation. (Shown here as a Union

General in the Civil War.)

|

|

| |

I know our Great Father has power to do

with us as he pleases; we have been driven from our homes

several times by the whites, and all we want is a permanent

location, where we shall be free from further molestation.

. . .Heretofore we have had our enemies, the whites on one

side, and the Comanches on the other, and of the two evils,

we prefer the former, as they allow us to eat what we raise,

whilst the Comanches take everything, and if we are to be

killed, we should much rather die with full bellies; we would

therefore prefer taking our chances on the Brazos, where we

can be near the whites.

|

|

|

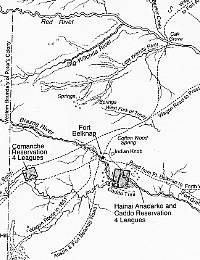

"Marcy Map" of 1854 "Map

of the Country upon Brazos and Big Wichita Rivers Explored

in 1854, Embracing the Lands Appropriated by the State

of Texas for the Use of Indians."

|

Detail of original Marcy Map showing area where Brazos

Reservation was established. |

The mesquite- flat country around

the Brazos Reserve was a very different environment

from the Caddo Homeland: drier with shallow and less

fertile soils. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

This painting by Nola Davis based

on Remmington's "Twilight of the Indian" brings

to mind the Caddos' days on the Brazos Reserve. Courtesy

Texas Parks and Wildlife.

|

|

A

reserve of 37,152 acres, for the Anadarko, Caddo, Waco, Kichai,

Delaware, Twakoni, and Tonkowa, was commonly called the Brazos

Reserve. It was situated on the main branch of the Brazos a

few miles below Fort Belknap in present Young County. A separate

reservation for Comanches was called the Upper Reserve.

The Caddo, Hainai and Anadarko gathered in March

1855, eager to break the tough prairie grass sod and plant

fields in ground they could call their own. It was a dry spring—no

rain for nine months. Four hundred acres were planted but

the seeds, dropped late in dry earth, did not yield enough

to make the effort worth while. Two-hundred-five Anadarkos

(Hainai were counted with the Anadarkos) and 188 Caddos settled

in villages next to dried-up fields.

Drought and grasshoppers spoiled the next two crops as well.

But the following year forecast a good life in villages with

traditional grass houses, neat cabins, and gardens full of

vegetables and melons. The chiefs and the agents worked together

to organize law and order. A government farmer lived at the

agency in the middle of the reserve and worked with the people

to develop their fields and stock. A resident blacksmith took

care of tools and weapons.

The Caddos built seven good log houses and

had 130 acres in corn, 20 in wheat in 1857. The Anadarkos

built ten log houses and had 115 acres of corn and 20 acres

of wheat. Particular attention was given to raising stock

and the number of horses, cattle and hogs steadily increased.

The women milked and made butter. There were few deaths and,

for the first time in many years, children were thriving.

Finally, in 1858, a schoolhouse was built and the teacher

soon had sixty pupils.

Outside the Reserve, the landscape was changing. When Neighbors

and Marcy surveyed boundaries for the reserves, a wide stretch

of mesquite-dotted country lay between Texas settlers and

the Indians. But in less than three years, while the Caddos,

Anadarkos, and Hainais built and planted, a boom of new settlers

came to Fort Belknap and Young County. Complaints that the

federal government provided too little protection rose with

the increasing white population. Hostile Indians, mostly from

north of Red River, raided Texas settlements. They made an

easily followed trail to the Brazos Reserve and then scattered

so that no trail was visible above.

Small groups of self-appointed protectors ready

to believe the worst about any Indian, concluded that all

their troubles were caused by reserve Indians. A leading troublemaker

was John R. Baylor who had been dismissed as the first agent

for the Comanches on the Upper Reserve. His inflammatory remarks

in public letters and mass meetings of citizens excited prejudices

and roused emotions.

The year the schoolhouse was built on the Brazos

Reserve, Texas Governor H. R. Runnels authorized J. S. Ford

to organize a hundred Texas Rangers. Ford brought his Rangers

to the Reserve to enlisted the tribes' help in a war against

the Comanches across Red River. The chief's called in to council

willingly agreed to send about one hundred warriors. They,

too, had suffered the loss of great numbers of livestock to

raiders from across the River and had been subjected to unjust

blame for depredations those Indians had committed upon white

settlers.

Ford directed an attack on Comanches camped

near the Canadian River on May 12. A running battle covering

over six miles began about seven in the morning and lasted

until Ford declared a victory about two in the afternoon.

He gave the Indian captains his highest praise saying, "They

behaved under fire in a gallant and soldier-like manner and

I think they have fully vindicated their right to be recognized

as Texas Rangers of the old stamp."

That fall, 1858, 125 Anadarko, Caddo, and other

Brazos reserve warriors again cooperated in successful campaign

against the northern Comanches. This time they rode in support

of 400 U.S. cavalry led by Major Earl Van Dorn. The Major

asked them to accompany him again on his spring campaign.

They planned to do so, but for now their horses needed rest

and fattening.

Agent Ross gave Tom, a Choctaw married to an

Anadarko woman, permission to take his wife, some of his grandchildren,

and other family connections a few miles below the reserve

where there was good grass for grazing. All together there

were twenty-seven people in the party—eight men, eight

women, and eleven children. They set up five camps above Golconda,

in Palo Pinto county. Late fall eased into an early winter

and hunting season. Several white men came to ask Tom's family

to go with them on a bear hunt. The family agreed and moved

camp to the edge of a small creek about 15 miles below the

reservation. Near daylight, before anyone was awake, gunshots

pierced their tents. Choctaw Tom's wife, another Anadarko

woman, three Anadarko men, a Caddo man and Caddo woman were

killed. Six died instantly on the beds where they slept; the

seventh was able to reach his gun and crawl through the tent

flap before he died. José Maria's nephew, Little John

who had served with Van Dorn, was one of the young men killed.

A thumb was shot off the hand of Tom's daughter. Another woman

and three men had severe wounds. Eight children were injured,

three seriously. The name's of the men who participated in

the massacre were known. They made no secret of their identities.

People who lived near the camp left their homes.

Agent Ross was away so it was left to J. J. Strum, the government

farmer for the Brazos Reserve, to explain that the settlers

were afraid of blame and retaliation. José Maria and

the Caddo chief, Tinah, said tell them "We are not wild

Indians and will not harm the innocent." They said Strum

should send someone to tell those settlers, most of whom were

friends, to return to their homes and take care of their farms.

The Caddo and Anadarko did not blame them—they had been

told that the men who killed members of their families would

be caught and punished according to the white man's law, and

that was the way it should be.

That is not the way it was. There were no arrests.

At an official examination of the murders that took place

in Waco, the grand jury described the Brazos reserve as a

nuisance. Stating that the Indians there were doing all the

mischief they concluded, "It is now the prevailing sentiment

that we must abandon our homes and take up arms against the

reserved Indians." Instead of charging the admitted murderers,

the jury found José Maria guilty of stealing a mule.

Near the end of February, Comanches stole 80

horses from the Caddo—about the last of some five hundred

head they and the Anadarko had three months earlier. In May

a Caddo Indian named Fox, was brutally killed while carrying

a official dispatches from Agent S.A. Blain at Fort Arbuckle

in Indian Territory to Agent Ross at the Brazos Reserve. Agents

were accustomed to expressing dispatches between reservations

by reliable members. They had known Fox since boyhood, he

had done good service in Ford's and Major Van Dorn's fights.

An army officer accompanied by a party of Indians from the

reservation went to Jacksboro in search the men who murdered

Fox. This incident was used by John R. Baylor to spark an

attack on the reserve.

On the morning of May 23, 1859, Baylor led a

force of two hundred fifty men onto the Brazos Reserve. An

infantry company from Fort Belknap reinforced a guard that

had been posted at the agency. Baylor and his company drew

their mounts up in a single line within 600 yards of the agency.

He told the officer sent to meet him that he had come to fight

Indians, not whites, but if the troops fired on his men, they

would fight back. The Captain in command said his orders were

to protect the Indians on this reserve from the attacks of

armed bands of citizens and he would do so to the best of

his ability. Baylor backed off and set up camp outside the

border of the Reserve. At the same time he declared that the

warning did not alter his determination to destroy the Indians.

Neighbors urged the Office of Indian Affairs

to authorize immediate removal of the tribes to a temporary

location north of the Red River at Fort Arbuckle. Instructions

were finally written on June 11—pack up and move.

The Removal

The thermometer reading on the Brazos Reserve

for the past month had averaged 106 degrees from midmorning

until five in the evening. The gauge was no different on the

first day of August when the families of the Caddo, Anadarko,

Hainai and associated bands left their houses, gardens, almost

all their stock and all possessions they could not carry.

The whereabouts of Baylor and his mob was not known, but it

was possible that they would try to carry out their threat

to kill all the Indians as soon as they were off the Brazos

Reserve. Two companies of cavalry and one of infantry provided

a protective escort. Wagons carried military provisions for

five months. The very old and infirm rode, the very young

and small were carried, most walked the arid two hundred mile

trail that ended on the bank of the Washita River near present

Anadarko.

|

Redrawn version of the Marcy Map of 1854 showing the Brazos

Reservation. From Carter, 1995. |

Detail of redrawn version of Marcy

Map of 1854. From Carter, 1995.

|

|

Brazos Indian Reservation School

Operated for Indian children living on Brazos Reservation,

a 37,000-acre refuge created by state in 1854. Here

over 1,000 Anadarko, Caddo, Delaware, Ioni, Shawnee,

Tawakoni, and Tonkawa people lived, farming and acting

as U.S. Army Scouts. Despite racial strife outside reserve,

teacher Z. E. Coombes (1833-95) reported unusual good

will and harmony in classroom. Subjects taught were

English, spelling, writing, and arithmetic. From 34

to 60 students were enrolled. School closed when Indians

were moved north in 1859.

Texas Historical Marker

|

| |

|

|

| |

Esther Hoag Hornovich:

He often told us that there was different

bands of Caddos at the point of—course of the Red River.

He said they were called Kahadoches—they were up around

in there, a large group of them. Several villages, but it

see like he said towns, I do not know the exact words in Caddo,

but he said there were some Hanai groups, and then along the

Sabine River . . . . there were bands living along the Angelina

River and Colorado River and some at the point of Sabine around

in that area and along the limestone caves and around Santa

Marcus. . .And that was told him by Grandmother. . .He said

all the bands including a few of the tribes that were with

the Caddos . . . were brought to Washita Valley . . . and

he said there was others also from the east that had to come

later. . .I mean now eastern Oklahoma and in that vicinity—Choctaw

country. The Whitebead family and some others—The Nedarkos

[Nadacos, Anadarkos] were not living below Belknap

before that time. They were living in east Texas somewhere

or Louisiana. . . that was their beloved home and when they

[Caddos] made this treaty and they wanted them to move on,

that they were paid and later on they moved away from there

to west from there towards the Angelina River with other tribes

that were already there of their people. . .I do not know how

the map is. Anyway it's close to this Angelina River. . .all

I remember of the ones he named was mainly his own people

and the Nadaco and there was the Iona [Hainai]

Band which was similar to the Nadaco . . . it seems that the

white people in East Texas wanted the fertile land down there

and they wanted them removed so when they were removed and

given certain tract of land there [the Brazos Reserve] for

their permanent establishment but it seems later on in a few

years, at least four years, they had this trouble with Baylor

and his men. . . . he did not remember anything because he

was a small baby when they moved there [Oklahoma]. . . the

soldiers brought them and they kept the old folks, old ladies

and small children in a wagon. I did not pay attention to haw

many they had. My Grandmother, she walked all the way and

her sisters, and her daughter, my oldest aunt, took turns

carrying my daddy because he was too heavy.

Esther Hoag Hornovich,

daughter of Enoch Hoag,

Jose Maria's son

|

|

|