Three generations of Whitebread family

descendants celebrate their Caddo heritage during a

parade in Andarko, Oklahoma. Photograph courtesy Donna

Spaulding Smith.

Click images to enlarge

|

Julia Edge and her parents, 1908.

Julia was one of the last generations born and raised

speaking Caddo. In the 1970s, historian and Caddo tribal

member, Cecil Carter, spent many hours talking with

Julia Edge and carrying on the Caddo oral tradition.

Archives and Manuscript Division, Oklahoma Historical

Society.

|

Drum Dance underway at the dance

ground at the Caddo Tribal Center. Photograph by Dayna

Bowker Lee, folklorist and anthropologist at Northwestern

State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Lee has

done ethnohistoric research on the Caddo tribe and she

often attends tribal dances to document modern Caddo

traditions.

|

Henri Joutel's journal provides an

eyewitness account of his 1687 journey through the Caddo

Homeland. Historian William Foster's editorial

notes help put Joutel's observations into meaningful

context. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

|

This study by famed historian Herbert

Eugene Bolton was not published until 1987, at least

50 years after it was written. Although belated, it

is still an important compilation of early Spanish accounts

concerning the Hasinai Caddo. Published by the University

of Oklahoma Press.

|

Color plate of late Caddo pottery

vessel excavated by C.B. Moore in 1911 from the Haley

site along the Red River in southwestern Arkansas. Moore

was the first archeologist to systematically explore

portions of the Caddo Homeland.

|

1979 dig during an archeological

field school held by Stephen F. Austin University

in Nacogdoches, Texas under the direction of professor

James Corbin. The Reavley House Mound is a surviving

remnant of a 700-year-old Caddo ritual center. Photo

courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

Alex Krieger is regarded as the first

real scholar to take an interest in Caddo archeology.

Photograph from TARL archives.

|

1950 Caddo Conference participants

comparing and discussing pottery types. From left to

right, Alex Krieger, Clarence Webb (conference host),

John Cotter, Walter Hagg, and Lynn Howard. Photograph

by Robert L. Stephenson, TARL archives, Louisiana G-1.

|

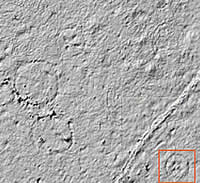

Section of geophysical map showing

a small area at the George C. Davis site in which at

least three structural patterns are readily discernable.

The orange square highlights a circular pattern of a

building about 11 meters (36 feet) across with four

internal roof supports and a hearth in the middle. The

angled line running through the image is one of the

signature of one of the interpretive footpaths at Caddoan

Mounds State Historic Park. (The right-angled glitches

are minor data/processing gaps.) Courtesy Darrel Creel

and Dale Hudler, TARL.

|

|

Oral history, written history, linguistics,

ethnography, ethnohistory, bioanthropology, and archeology

each provide critical clues about the long march of Caddo

history. Here we briefly mention some of the major sources

of knowledge and highlight the strengths and limitations of

each. Sophisticated understandings of the complex and lengthy

history of Caddo peoples can only come through combining sources

of information and checking one against the other.

Oral tradition remains important to Caddo

people, but the most essential context for maintaining that

tradition—Caddo language—is gravely imperiled. Anthropologists

and linguists have shown that languages and cultures are so

intimately linked that one can hardly exist without the other.

Languages become extinct when children are no longer raised

speaking the mother tongue, and that has been the case with

the Caddo for at least a generation. There are still about

30 fluent Caddo speakers, but none is young. A small nonprofit

foundation, Kiwat

Hasinay, is dedicated to preserving the Caddo language

and encouraging its revival. One of the foundation's projects

has been an effort to create a community-based program to

teach the language to Caddo children. Through such efforts

and through shared stories, song, and dance, Caddo peoples

will continue to pass on important memories of the Caddo past

and present. In doing so they are creating a new living tradition,

a celebration of Caddo history and identity.

Caddo oral traditions have entered into the

written record in various ways. Some are known through the

records of linguists and ethnographers who have interviewed

Caddo elders and translated their stories. The work of linguists,

those who study the nature and structure of language, is discussed

in the "Caddoan

Languages and Peoples" section. Linguistics is sometimes

considered a subfield of anthropology and sometimes a separate

field of its own. Unfortunately, only a single linguist, Wallace

Chafe, has intensively studied the Caddo language in modern

times and the major results of his work have not been published.

Ethnographers are anthropologists who

study and describe other cultures by visiting, observing,

and asking questions. The best ethnographers are "participant

observers" who spend extended periods of time living

in the community they are studying and learning the native

language. Unfortunately, by the time ethnographers began visiting

the Caddo in the early 1900s, Caddo society had been radically

altered by historic events. Still, ethnographers and folklorists

such as George Dorsey (working in 1903-1904), John

Swanton (ca. 1911), and Elsie Clews Parsons (1930s)

interviewed Caddo elders who were raised speaking Caddo. Modern

historians such as Cecile Elkins Carter have

carried on this tradition by interviewing Caddo elders and

recording their recollections and stories.

Ethnohistorians are anthropologists who

use documentary evidence to glean ethnographic observations

and understandings of aboriginal societies. Their work overlaps

with that of traditional historians, but stands apart

because ethnohistorians are more concerned with reconstructing

the nature of aboriginal societies rather than the sequence

of events and the impact of individuals. Historians and ethnohistorians

are both limited by the surviving documents; there are relatively

few early accounts with substantive detail about Caddo life

and Caddo peoples. Still, new documents and new versions of

known documents are still being discovered from time to time

in archives. New insight also can be gained from improved

translations of known documents.

The work of John Swanton, a student of

the famed ethnographer Franz Boas, is widely regarded as the

most important ethnohistoric study of the Caddo. His 1942

book, Source Material on the History and Ethnology of the

Caddo Indians, combines his own observations with cautious

interpretations of those made by various explorers, missionaries,

soldiers, and more. The eyewitness accounts of early Spanish

and French visitors to the Caddo Homeland are primary sources

of knowledge. Such observations are also often highly biased

and selective, reflecting the prejudices, motives, and abilities

of the observer as much or more than the character of the

observed.

Two early chroniclers of Caddo life stand out.

Henrí Joutel, a young Frenchman who survived

La Salle's disastrous colony on the Texas coast, spent four

months traveling through the Caddo Homeland in the spring

and summer of 1687. His remarkable journey included visits

to Hasinai villages in the Neches-Angelina drainages, the

Nasoni village (see "Upper

Nasoni" exhibit) and others linked to the Cadohadacho

along the Red River, and Cahino villages further east on the

Ouachita. Joutel's journal contains invaluable observations

about the Caddo world as seen by an intelligent observer who

had no real ulterior motive other than to survive.

Only a few years later, the Spanish priest,

Francisco de Jesús Maria Casañas, spent

15 months (1690-1691) living among the Nabedache (the westernmost

Nasinai group) on the Neches River. He was part of the Spanish

expedition that founded the first mission to the Caddo, Mission

San Franciso de las Tejas in present day Houston County, Texas.

Fray Casañas was a devoted priest motivated by the

desire to save heathen souls, but he was also a shrewd observer

who stayed long enough in one place to get a real sense of

the annual cycle of Caddo life. His Relacíon

was written while in residence at the mission.

The primary documents written by Joutel, Casañas,

and many others did not become well known until the 20th century

when professional historians began translating and studying

these sources. Famed historian Herbert Eugene Bolton

became interested in the Hasinai Caddo in 1906 and studied

many of the primary documents on and off over the next several

decades. Regrettably, his manuscript on the Hasinai was not

published until 1987, long after his death in 1953 and at

least 50 years after it was written. Apparently he was never

satisfied with what amounted to an ethnohistorical study.

As a consequence, Bolton's work did not have the impact it

would have had, had it been published in a timely fashion.

Bolton's posthumous book, The Hasinais: Southern Caddoans

as Seen by the Earliest Europeans, covers much of the

same material presented in a similarly titled 1954 study by

William J. Griffith, The Hasinai Indians of East

Texas as Seen by Europeans, 1687-1772. Late in life, Bolton

encouraged Griffith's work, apparently believing that his

own would never be published.

In the last few decades a number of historians

and archeologists have published historical accounts of Caddo

peoples. These include traditional historians such as Todd

Smith and David LeVere and historically minded

archeologists such as Kathleen Gilmore, George Sabo,

and Timothy K. Perttula, as well as several historians

who are also members of the Caddo tribe. Hasinai: A Traditional

History of the Caddo Confederacy by Vynola Newkumet

and historian Howard Meredith was the first such study

(1988). Cecile Elkins Carter's 1995 book Caddo Indians:

Where We Come From synthesizes history, oral tradition,

and archeology from a Caddo perspective.

Bioanthropologists (also known as biological

or physical anthropologists) study the skeletal remains from

archeological excavations at Caddo sites. This research domain

has yielded extremely valuable data available through no other

means. By studying human bones, bioanthropologists can look

at the health of individuals and their diet, age, sex, incidence

of disease, and evidence of trauma, such as broken bones.

Some information comes from careful scientific examination

and measurement, but some studies require the destruction

of small samples of bone. Such samples can, for example, be

used for radiocarbon dating and for determining carbon and

nitrogen isotope values, which reflect diet. By comparing

samples from individuals dating to different time periods

and from different areas of the Caddo Homeland, one can examine

broad patterns of health and nutrition. While such studies

have been done very successfully in some parts of the country,

the human remains in the Caddo Homeland are often very poorly

preserved or completely destroyed by acidic soils.

From a scientific perspective, studies of human

remains can be very informative. But many Caddos and other

Native Americans feel very strongly that any disturbance of

their ancestors' graves is wrong. Some view archeological

excavations of graves as grave robbing and oppose all forms

of bioanthropological analysis. Others see the value of some

studies, particularly the non-destructive ones, when graves

lay unalterably in the path of "progress." Still

others do not object to destructive testing when it is being

done for a solid scientific purpose that promises to shed

light on Caddo history. See "Graves

of Caddo Ancestors" for more discussion of this controversial

topic.

Archeologists study early Caddo

history by documenting, mapping, and excavating Caddo sites

and examining "material culture," meaning the tangible

physical remains such as pottery, stone tools, animal bones,

and so on found at the sites. Since archeologists have been

investigating sites in the Caddo Homeland for almost a century,

a thorough review of the history of investigation would be

lengthy. Here we will outline only the major developments.

The first systematic archeological exploration

of the region began around 1908 through the efforts of Clarence

B. Moore of the Philadelphia Academy of Science. Moore's

elaborately illustrated reports of his work at sites along

the Red and Ouachita rivers are valuable sources of information.

In fact, his observations are all that will ever be known

of several mound sites that were subsequently destroyed by

the meandering Red River. Moore's work in the Caddo area was

followed by the 1917-1920 explorations in the southern Ouachita

Mountains by Mark R. Harrington on behalf of the Heye

Foundation of New York.

By 1920s, it was thought that the mound sites

along the Red River in Arkansas and Texas were probably associated

with the Cadohadacho and that sites in the Neches-Angelina

drainages in east Texas were linked to the Hasinai. In 1930,

with modest funding from the Smithsonian Institution, the

University of Texas began undertaking major excavations at

a number of Caddo sites in east Texas under the supervision

of James Pearce and his field director, A. T. Jackson.

After the mid-1930s, funding and manpower from the WPA (Works

Progress Administration) allowed the University of Texas to

expand its work in east Texas.

Like Moore, the University of Texas archeologists

chose prominent mound sites like the Hatchel Mound near Texarkana

(see Upper

Nasoni exhibit) and the Sanders site north of Paris, Texas,

and locales where prehistoric cemeteries were known to exist.

Graves were sought out because they often contained whole

pots and other interesting objects. Similar excavations were

undertaken at Caddo sites in Oklahoma and Arkansas in the

1930s under the WPA. Such projects resulted in a great many

whole and fragmentary pottery vessels and many other artifacts,

but little real appreciation of Caddo history and few substantive

publications. This was to change in the 1940s as the result

of the efforts of the first real scholar to take an interest

in Caddo archeology, Alex D. Krieger.

Krieger was placed in charge of the WPA lab

at the University of Texas in Austin in the late 1930s and

soon began systematic comparisons among collections from different

sites in the Caddo area. During World War II, he wrote the

first synthesis of Caddo history based on his comparative

studies as part of his larger 1946 study Culture Complexes

and Chronology in Northern Texas. He continued this work

during his analysis of the artifacts from the George C. Davis

site. The Davis site near Nacogdoches, Texas, had been excavated

in 1939-1941 by the WPA under the direction of a skilled and

meticulous field archeologist, Perry Newell. Newell

died just after World War II, leaving Krieger to finish their

now-famous 1949 report, The George C. Davis Site, Cherokee

County, Texas.

In these two studies, Krieger synthesized the

culture history of the "Caddoan" area, including

Spiro and the Arkansas Basin. He defined Early Caddoan (Gibson

aspect) and Late Caddoan (Fulton aspect) periods as well as

thirteen geographical clusters (foci) across the Caddoan area

that he thought represented closely related sites. Krieger

put quote marks around the term "Caddoan" because

he realized the area had a more diversity than implied by

the label. While many of Krieger's concepts were later refined

or discarded, his work brought national recognition of the

Caddo area and of its relationship to parallel developments

in the lower Mississippi Valley and elsewhere in the Eastern

Woodlands.

One of Krieger's most important collaborators

was Clarence H. Webb, a pediatrician from Shreveport,

Louisiana, who became a very influential Caddo archeologist.

Webb began investigating Caddo sites along the Red River in

northwestern Louisiana in 1935 and kept at it for the next

45 years. While Webb had no formal training in archeology,

his medical education, familiarity with the area, and aptitude

more than made up for it. Webb's energy, enthusiasm, and long-term

persistence were unmatched. Working on weekends and vacations,

Webb and his friends conducted excavations at numerous major

Caddo sites including Mounds Plantation, Gahagan, and Belcher.

He reported the results in conference presentations, journal

articles and monographs, including one entitled The Belcher

Mound: A Stratified Caddoan Site in Caddo Parish, Louisiana

that was published in 1959 as a Memoir of the Society for

American Archaeology. Through such efforts he succeeded in

demonstrating the antiquity of Caddo and pre-Caddo settlement

in the region. He also pioneered the use of the direct historical

method in the Caddo area, tracing Caddo patterns back in time

from historical records into prehistory.

Webb was instrumental in starting a very useful

scholarly tradition, the Caddoan (or Caddo) Conference.

The first conferences in the late 1930s were informal gatherings

at Webb's house attended by only the handful of researchers

who knew or cared about Caddo archeology (Krieger and Newell

were among them). As time went on the Caddo Conference became

a more regular, and then annual, event attended by dozens

and sometimes hundreds of researchers, students, and enthusiasts.

These conferences were and are essential devices for breaking

down the state-line barriers and uniting archeologists in

Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas. By the 1970s Caddo

tribal members began participating in the conference, resulting

in improved communication between the archeologists and the

Indians whose ancestors they studied.

In recent decades there have been dozens of

major investigations at Caddo sites and hundreds of smaller

ones. In 1960s and 1970s reservoir salvage archeology provided

the impetus and opportunity to undertake research at a number

of important locales within the Caddo Homeland in Oklahoma,

Texas, and Arkansas. Since the late 1970s, federal and state

cultural resource laws have led to much more archeological

work in the region. In fact, contract or CRM (cultural

resource management) archeology accounts for most of the research

done at Caddo sites over the last 25 years. Although many

CRM projects are small and the results usually reported in

technical reports of limited distribution, excellent research

has been accomplished on smaller sites that probably would

not have attracted other researchers. CRM projects have also

provided the first systematic surveys in the Caddo Homeland,

recording many small habitation sites in places archeologists

had previously ignored.

Despite the increase in CRM-related investigation,

the Caddo Homeland has seen less concentrated research than

many other areas of the Eastern Woodlands. One of the main

reasons for this inequity is that major public and private

universities in all four states are situated outside the Caddo

area. As a direct consequence, the region long lacked resident

professional archeologists. Fortunately, two changes have

occurred. One has been the hiring of archeologists as teachers

at several smaller universities in the area. In Texas, James

Corbin at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches

has been active in Caddo archeology as has Hiram Gregory

at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana.

The other welcome change has been the establishment of regional

"station" archeologists in Arkansas and Louisiana

in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively. This has meant that

professional archeologists are living and working in the Caddo

Homeland year round. Archeologists Ann Early (now Arkansas

State Archeologist), George Sabo, and Frank Schambach

in Arkansas, as well as Jeff Girard and George Avery

in Louisiana have made major contributions. Typically,

the station archeologists also teach at small universities

and colleges in the region.

In Texas and Arkansas and, to a lesser extent,

Oklahoma and Louisiana, state and regional archeological societies

and associations have held field schools and conducted research

at numerous Caddo sites. Such organizations are made up of

avocational (amateur) and professional archeologists. In Arkansas

and Louisiana, avocational archeologists usually work with

the regional and station archeologists. In Texas and Oklahoma,

avocational archeologists sometimes work with the state historic

preservation offices and sometimes work on their own.

Today archeologists are asking new questions

and applying new technology to learn more about Caddo ancestors.

Darrell Creel, director of TARL, and Samuel Wilson,

professor of anthropology at UT Austin, are currently directing

new investigations at the George C. Davis site. Their goal

is to create a detailed map of the Early Caddo settlement

using state-of-the-art geophysical survey equipment. This

equipment allows archeologists to detect subtle magnetic variations

created 700-1200 years ago by Caddo builders. The result,

as can be seen to the left, are nothing short of amazing.

The use of such non-destructive techniques holds great promise

for the future of Caddo archeology.

|

Donna Smith Spaulding and young Caddo

friend, LaDawna Supernaw, in traditional dance clothes.

Although the Caddo language is no longer spoken by Caddo

children, Caddo traditions and ceremonial regalia are

passed down from generation to generation. Photograph

courtesy Donna Smith Spaulding.

|

Portrait of Julia Edge as a Caddo

elder in the late 1970s. Photo by Cecile Carter.

|

The 1996 edition of John Swanton's

classic Caddo source book originally published in 1942.

Published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

|

| |

|

There are normally eight or ten families in these

huts, which are very large; some are 60 feet in diameter…

These are round, in the shape of beehives, or rather

like large haystacks … They are covered with grass

from the ground to the top. They make a fire in the

center, the smoke going out the top through the grass.

(Henri Joutel, describing the houses he saw among the

Hasinai groups in 1687.)

|

Cecile Elkins Carter's 1995 book

synthesizes history, oral tradition, and archeology

from a Caddo perspective. Carter also wrote the "Caddo

Voices" section of the Tejas online exhibit. Now

available in paperback from the University of Oklahoma

Press.

Cecile Elkins Carter's 1995 book

synthesizes history, oral tradition, and archeology

from a Caddo perspective. Carter also wrote the "Caddo

Voices" section of the Tejas online exhibit. Now

available in paperback from the University of Oklahoma

Press. |

Timothy Pertula's 1992 book summarizes

archeological and ethnohistorical data on the period from

about A.D. 1520 to 1800. Now available in paperback from

the University of Texas Press.

Timothy Pertula's 1992 book summarizes

archeological and ethnohistorical data on the period from

about A.D. 1520 to 1800. Now available in paperback from

the University of Texas Press. |

| |

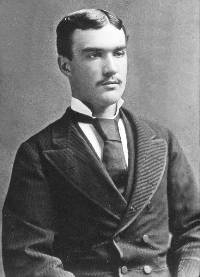

Clarence B. Moore as a young man

at Harvard College. Years later, under the sponsorship

of the Philadelphia Academy of Science, Moore undertook

the first systematic archeological exploration of Caddo

sites along the Red and Ouachita rivers. His observations

are all that will ever be known of several mound sites

that were subsequently destroyed by the meandering Red

River.

Clarence B. Moore as a young man

at Harvard College. Years later, under the sponsorship

of the Philadelphia Academy of Science, Moore undertook

the first systematic archeological exploration of Caddo

sites along the Red and Ouachita rivers. His observations

are all that will ever be known of several mound sites

that were subsequently destroyed by the meandering Red

River. |

Rare photo of A. T. Jackson, a former

newspaper reporter who became James Pearce's chief field

archeologist. It was Jackson who directed most of the

excavations at Caddo sites in northeast Texas that the

University of Texas undertook in the 1930s. Jackson

is rarely seen in archival photos, in part because it

was he that usually took the photos. This photo was

taken in 1931 at the J. E. Galt farm in Franklin County.

TARL archives.

|

This 1949 report brought national

attention to the Caddo area. The Society for American

Archeology issued a new paperback edition in 2000 with

an introduction by Dee Ann Story.

|

Workers clean out the postholes of

a large building at the A.C. Saunders site in 1935 under

the direction of A.T. Jackson of the University of Texas.

TARL archives.

|

Archeologists at work at the George

C. Davis site in Cherokee County, Texas, 1969. The complex

layers of earth are clearly visible in the walls of

Mound C. TARL Archives.

|

Workers from the University of Texas-WPA project uncovering

structural remains within the Hatchel Mound near Texarkana

in 1938. This archeological excavation was among the

largest ever undertaken at a Caddo site. Photograph

from TARL archives. |

Test excavations in 2003 at the

Hatchel-Mitchell site under the direction of Tim Perttula.

The team is exploring the village area, instead of the

mound and graves targeted by the 1930s WPA work. Photo

by Mark Walters. |

|