Summer dance at Caddo tribal dance

grounds, Binger, Oklahoma. Photograph courtesy Donna

Smith Spaulding.

Click images to enlarge

|

Caddo dance, 1892. Courtesy Marilyn

Murrow. Photograph from Archives and Manuscripts Division,

Oklahoma Historical Society.

|

Caddo drummers seated at a dance.

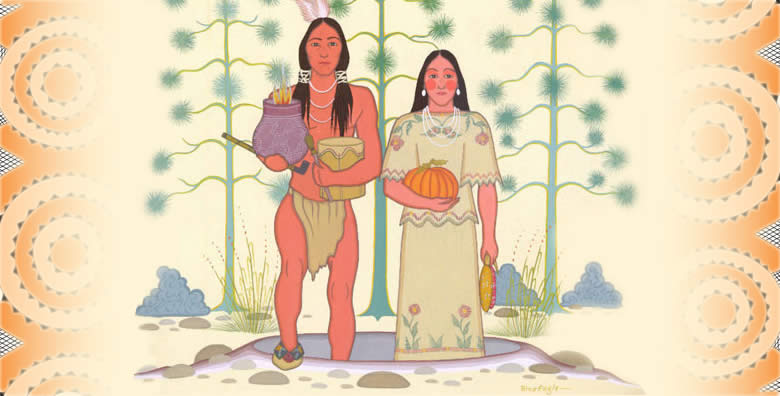

This painting by Caddo artist Thompson Williams is based

on an 1892 photograph. Courtesy Senior Citizen Center,

Caddo Tribal Headquarters, Binger, Oklahoma.

|

|

Caddo communities were protected by the large size

of the Caddo territory, the Caddo's reputation as fierce

and skillful warriors, and their ability to band together

in times of crisis. Their neighbors near and far knew

not to enter Caddo territory without permission unless

they were looking for a fight.

|

Map of Upper Nasoni settlement on

the Red River, produced by the Spanish expedition of

1691-1692, led by Terán del Rio. This village

was part of the Cadohadacho alliance. The map shows

that the community consisted of small farmsteads or

extended family compounds, each depicted as being surrounded

by rows of trees or bushes. On the left is a mound with

a "templo" on top. The settlement shown is

believed to have stretched along several miles of the

Red River. Original (uncolored) map in the Archivo General

de Indias, Seville.

|

Ancient Caddo potters created an

extraordinary variety of pottery vessels from huge storage

jars over three feet high to tiny bowls probably made

for children. These examples are from the TARL collections.

Photograph by Sharon Mitchell.

|

Whitebread, Caddo chief (caddi) from

1902-1913. Chief Whitebread, whose Caddo name translates

literally as "bread white," was a major source

of information on Caddo traditions for ethnographers

George Dorsey and John Swanton.

|

José Maria, famous chief of

the Anadarko (Nadaco), who rose to become principal

chief of all Caddo groups during the turbulent years

of the mid-1800s. José Maria, whose Caddo name

was Iesh

(Aasch), was famed both as a warrior and statesman.

It was he who led the Caddo from the short-lived Brazos

Reserve in Texas to the Indian Territory in 1859. This

bronze bust by sculptor Leonard McMurry is on display

at the National Hall of Fame for Famous American Indians

in Anadarko, Oklahoma.

|

Sho-We-Tit (Billy Thomas), a Caddo

man photographed by Joseph Dixon on June 21, 1913 at

Anadarko, Oklahoma. This extraordinary portrait was

taken on an expedition funded by Philadelphia businessman

and philanthropist Rodman Wanamaker. Dixon and his assistants

presented American flags to Indian tribes across the

country. The expedition was intended to promote loyalty

to the United States and document the "vanishing

Indian race." Courtesy William Mathers Museum,

Indiana University.

|

|

Today the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma has some

4,000 members on its official tribal roll. The tribal headquarters

is in Binger, Oklahoma, about 45 miles west of Oklahoma City.

It was here, in and around the towns of Anadarko, Binger,

and Fort Cobb, that the Caddo settled during and after the

Civil War. This final relocation was preceded by over a century

of turmoil during which Caddo groups were forced to give up

their home territories in northeast Texas, northwest Louisiana,

southwest Arkansas, and southeast Oklahoma.

Today's Caddo are the descendants of many distinct

communities of people who shared much of a common culture.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, Spanish and French chroniclers

familiar with the Caddo homeland recorded the names of at

least 25 separate groups who spoke dialects of the language

known today as Caddo. Beyond speaking the same basic language,

these groups were linked by many shared customs, a similar

way of life, and by intermarriage.

Because of population loss and enemy encroachment,

most Caddo groups eventually organized themselves into the

Hasinai, Cadohadacho (also spelled Kadohadacho), and Natchitoches

alliances (often called "confederacies"). Group

consolidation took place in the Neches and Angelina river

valleys in east Texas (the Hasinai, comprised of the Hainia and other groups), the Great Bend area of

the Red River (the Cadohadacho), and in the vicinity of the

French post of Natchitoches, Louisiana. The Hasinai Caddo

continued to live through the 1830s in their traditional east

Texas homeland, while the Natchitoches did the same in western

Louisiana. But the Cadohadacho were forced to move west and south of

the Red River in the late 1780s, to the Caddo Lake area, along

the boundary between the U.S. territory of Louisiana and the

Mexican province of Texas. Some Cadohadacho stayed there until

about 1842, at the village of Sha'chahdinnih

or Timber Hill and several other poorly known villages.

When Europeans first arrived, the Caddo were

settled, farming people who grew corn, beans, squash, sunflowers,

and other crops and lived in farmsteads, hamlets, and villages

dispersed along streams and rivers that mainly flow to the

east and south through their homeland. Within this area the

forested Eastern Woodlands met the grasslands and savannas

that fringed the Great Plains farther to the west. Culturally,

the Caddo were the westernmost of the Indian societies of

the Southeastern United States, but their closest linguistic

and blood relatives were the Caddoan-speaking tribes of the

Southern and Central Plains: the Wichita, Kitsai, Pawnee,

and Arikara.

During the period from about 340 to 1000 years ago (A.D. 1000-1680), the Caddo, like

other Southeastern cultures, had "ranked" societies

with at least two social classes topped by the kin of the

hereditary religious and political leaders. Ethnologists sometimes

call such societies "theocratic chiefdoms" and recognize

that politics and religion were not separate domains but interwoven

parts of an intricate way of life. Although most Caddo communities

were scattered, and stretched out along river and stream valleys,

their most important leaders usually lived in or near the

larger villages and ritual centers

where towering temples built of poles and grass thatch stood

atop earthen mounds (see Teran map on left). At sacred

and festive times such as First Harvest and in times of crisis,

the scattered Caddo gathered where their society's leaders

lived.

The sprawling communities of the Caddo were

quite different from the compact fortified towns of other

societies along the central and lower Mississippi Valley,

a few days walk to the east. In 1541, the De Soto entrada

(intrusion) found fortified towns along the Mississippi River and

societies engaged in violent and habitual warfare. The Spanish

army sometimes attacked towns defended by well-organized warriors

and surrounded by stout log palisades and ditch works. But

as the Spanish moved farther west into the Caddo Homeland,

they came across open villages that were not fortified. Caddo

communities were protected by the large size of the Caddo

territory, the Caddo's reputation as fierce and skillful warriors,

and their ability to band together in times of crisis. Their

neighbors near and far knew not to enter Caddo territory without

permission unless they were looking for a fight.

Another thing that set the Caddo apart from

their neighbors was their extraordinary skill and creativity

as potters. Caddo women (and perhaps some men) made all kinds

of pottery from huge storage jars over three feet high to

tiny bowls smaller than a tea cup made for their children

as well as a variety of other objects including smoking pipes

and earspools. While much of the pottery was made for everyday

use in cooking, storage, and serving, the Caddo fine wares

also served other purposes (ritual and funerary) and are renown for their artistic craftsmanship.

Caddo potters were adept at combining flowing vessel forms

with polished surfaces that were characteristically decorated

with engraved designs. Other vessels had appliquéd,

brushed, incised, incisted-punctated or punctated designs, or were left plain. We know

that Caddo pots were valued by neighboring groups because

archeologists have found trade pieces hundreds of miles away

from the Caddo Homeland. In fact, it is the distinctiveness

of Caddo pottery that allows archeologists to trace, if imperfectly, much of

their early history.

The Caddo were also known as traders, famed

for their marvelous bows made of the wood of a tree the French

named bois d'arc ("bow wood," Osage orange)

and, their trade in salt. This trading

was an important part of Caddo life in the historic

era, as well as hundreds of years before European contact. The Caddo role as traders and, as information brokers,

was partly a consequence of the strategic position of their

territory between the Plains and the lower Mississippi Valley.

In the 17th century, the Spanish in northern Mexico learned

of the populous and prosperous Tejas Nation from the Jumano

Indians decades before Spanish expeditions reached the Caddo

homeland from the west in the 1680s. In the early 18th century French traders

were reportedly living in each of the major Caddo villages

along the Red River to take advantage of the Caddos' strategic

position and reputation as traders and middlemen. Soon large

quantities of deer and buffalo hides, horses and Apache slaves

from the Caddo and their trading partners to the west were

being exchanged for French guns and trade goods.

The name "Caddo" comes from Cadohadacho,

the name of one of the largest and most powerful groups in

early historic times, a people who lived mainly along the

Red River near its Great Bend. The Cadohadacho and their direct

ancestors had probably been living in the Red River valley for a thousand

years or more. "Cadohadacho" is often said to mean

"true chiefs" with the implication being that these

were the original Caddo, but this is a mistaken notion. (According

to linguist Wallace Chafe, the Caddo word, kaduhdááachu,

is a proper name whose full meaning and origin is lost; the

compound word contains a form of the adjective hadááchu,

meaning "sharp.") Other major Caddo groups have

equally long and distinguished histories, especially the Hasinai

groups who lived to the south in the Neches and Angelina

rivers basins in what is today east Texas. In fact, the Caddo groups

only became one people called the Caddo, after the mid-1800s,

when remnants of the many named groups united to save their

shared identity. Even today many Caddo people trace their

ancestry to one branch of the tribe or another.

Sorting out the various Caddo "branches"

is complicated and possible only to a limited degree. Over

the centuries prior to the arrival of Europeans, Caddo groups

had split apart from one another with "daughter"

communities breaking apart from "mother" communities

when moving into new territories in search of better farmland

and less crowding. The use of the terms mother and daughter

communities seems particularly appropriate because Caddo societies

traced their ancestry primarily through their mother's family.

In times of crisis, such as when enemies attacked, the most

closely related (and nearby) groups banded together into temporary

alliances identified with the strongest or principal social

group, which was often the older, mother community. The Cadohadacho

and Hasinai were the main groups who led the largest and most

influential alliances encountered by the Spanish and French,

while the Anadarko or Nadaco were another such unit. (These

are often misleadingly called "confederacies," a

term which implies a more formal union than was the case;

Caddo alliances were fluid and could be temporary.)

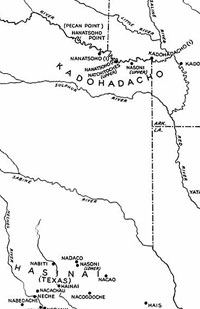

The 1942 map by ethnologist John Swanton shows

the approximate locations of some of the named groups/places

as recorded by the Spanish and French in the early 1700s.

Two principal alliances, the Cadohadacho and the Hasinai,

are shown as living in separate territories with a large intervening

area that appears to be unoccupied. This is, in part, a gap

of information rather than a complete absence of intervening

settlements. Swanton's map shows the areas known to the Europeans.

There is abundant archeological evidence that Caddo groups

were living in most parts of their traditional homeland in

the 16th and 17th centuries, but this settlement dispersion diminished after ca. A.D. 1680-1700. But by the time the Europeans

became familiar with the Caddo groups, many changes and consolidations

had already taken place as the result of the advance spread

of Old World diseases and the encroachment from the east and

north by opportunistic enemies such as the Osage and Chickasaw.

These developments impacted the easternmost Caddo groups first,

which explains why Swanton's map shows only the Cahinnio and

Ouachita villages to the east of the Red River.

|

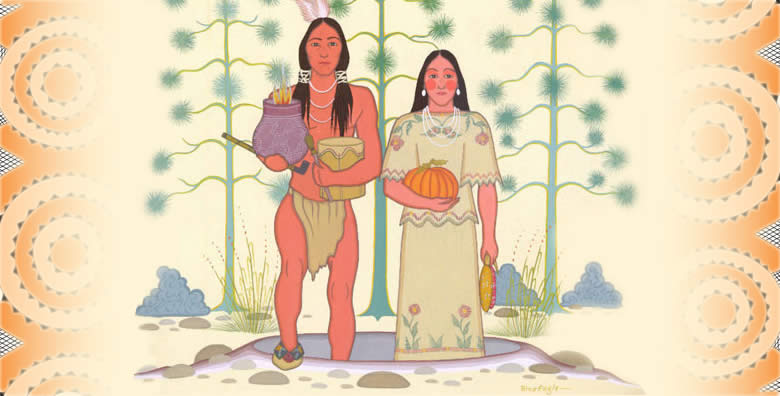

Artist's depiction of a Caddo woman

carrying a basket of freshly picked corn. Corn became

the Caddo's mainstay crop about 800 years ago and was

considered a sacred plant because of its importance

to Caddo life. Courtesy artist Reeda Peel.

|

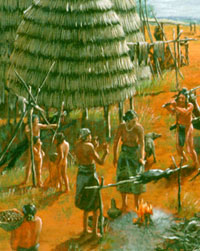

Artist's depiction of early Caddo

village, about 900 years ago. Painting by Nola Davis

on display at Caddo Mounds State Historic Park, Alto,

Texas. Courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

This map shows the relationship of

the Caddo Homeland to a few of the most important late

prehistoric civic and ritual centers that existed during

the heyday of the ancient Caddo, about 400-1000 years

ago (A.D. 1000-1600).

|

"Beef Issue at Fort Still"

painting by T.C. Cannon, son of a Kiowa father and a

Caddo mother. Courtesy of the Tee Cee Cannon Estate

and Joyce Cannon Yi, estate executor.

|

1894 photograph of Caddo family butchering

steer probably issued to family at the Anadarko Agency,

Oklahoma. Photo by Irwin and Mankins, from Archives

and Manuscripts Division, Oklahoma Historical Society.

|

Dance underway at the Caddo Tribal

Dance Grounds, Binger, Oklahoma, 1995. Photo by Cecile

Carter.

|

Mrs. Whitebread, wife of Caddo chief

(caddi), 1902-1913. Date of photograph unknown, probably

early 1900s. Courtesy Marilyn Murrow.

|

Heirloom silver broaches from Whitebread

family. Such pieces, typically made of German silver,

were worn around the turn of the century in much the

same way that conch shell artifacts were a thousand

years earlier. Photograph by Cecile Carter.

|

John Swanton's map showing the approximate

locations of some of the named Caddo groups and villages,

as recorded by the Spanish and French in the late 1600s

and early 1700s. From: Source Material on the History

and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians, 1942, Smithsonian

Institution.

|

|