Spiro and the Arkansas Basin in relationship

to the main Caddo Homeland and the Trans-Mississippi

South biographical zone. Base map by Erwin Raisz. Click

on image for enlarged view.

|

Reconstruction of a large rectangular

house at Spiro. This reconstruction is on display at

the site, now an Oklahoma state park. Photo by Dee Ann

Story.

|

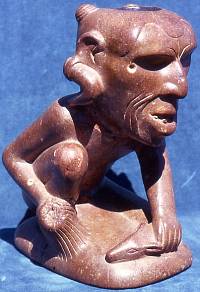

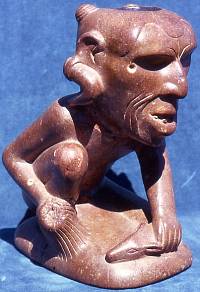

This unique human effigy pipe, depicts a naked man with

a larger-than-life head holding the head of a deer to

the ground in his left hand and a fringed object in

his right hand.

The pipe is made of red flint clay from a source near

St. Louis, Missouri not far from the great Mississippian

center of Cahokia. Thomas Emerson and colleagues believe

this pipe may be a hierloom item that was originally

made for use at Cahokia. Their hypothesis is that this

and similar ritual items left Cahokia in the late 13th

century as the center's power waned to be reused at

ascending centers like Spiro. Height 23 centimeters

(9 inches). Courtesy Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma

Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma. |

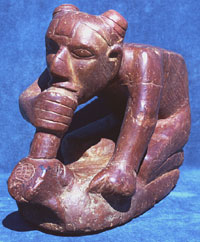

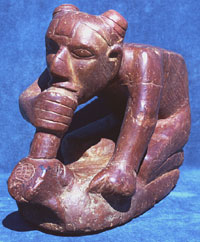

Effigy pipe of male figure crouching

and smoking what appears to be (upon close inspection)

to be a frog effigy pipe. Made of red flint clay from

near Cahokia. The pipe is 20.5 centimeters high and

36.5 centimeters long. Click to enlarge and see back

of pipe. Courtesy Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma

Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma.

|

Wooden mask with marine shell inlays

from Craig Mound, Spiro. The mask was carved from red

cedar and apparently was once covered with sheet copper.

Courtesy Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum

of Natural History, University of Oklahoma.

|

Spiro Engraved bottle and Crockett

Curvilinear-Incised bowl from Craig Mound, Spiro. Both

vessels are almost certainly Caddo vessels, probably

obtained from Red River Valley. Courtesy Robert Bell

and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma.

|

Bois d'arc (Osage orange) wood, one

of the best bow-making woods in North America, was traded

far and wide from its only source, a small area of the

Caddo Homeland near the Red River above the Great Bend.

Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

|

Spiro's wealth is almost certainly a consequence

of its strategic position as a "gateway" community

and trading center between the Mississippian world to

the east and the Great Plains to the west.

|

Caches of arrow points were common

offerings in Craig Mound. These are Agee points made

of novaculite and other materials. Courtesy Robert Bell

and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma.

|

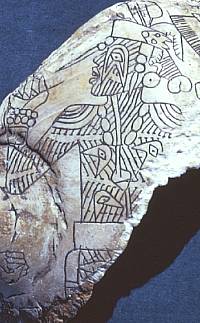

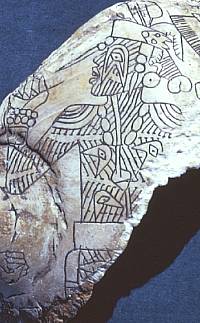

Engraved image of tatooed man on

marine shell cup from Craig Mound. Courtesy Robert Bell

and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma.

|

|

Just to the north of the main Caddo Homeland

lies the mound center of Spiro in the Arkansas River

valley in extreme eastern Oklahoma. Spiro was the westernmost

of the primate (main) centers in the Mississippian world during

the 12th through mid-15th centuries (A.D. 1100-1450). Spiro

was certainly not anywhere near as large or powerful as Cahokia,

the largest town and political capital in prehistoric America

north of Mexico. But Spiro is famous for the unprecedented

amount of wealth that was accumulated by its leaders and buried

with them.

In 1933, local entrepreneurs formed the "Pocola

Mining Company" to loot Craig Mound, the site's

largest mound. Craig Mound was actually four connected mounds,

a large cone-shaped one and three smaller ones. Digging by

hand with no real idea of what they were digging into, the

looters made relatively slow progress for the first year.

They did encountered many graves and offerings in the smaller

mounds and these began to appear on the market. This eventually

provoked a public outcry and Oklahoma passed one of the first

state laws protecting antiquities in 1935. Unfortunately,

the looters were able to continue digging secretly and finally

struck upon an effective way of getting what they wanted:

they hired coal miners to tunnel into the largest cone.

The main tunnel into the center of the mound

encountered a gaping hollow, the shell of a purposefully buried

mortuary building. Inside were elaborate special burials and

jumbled human bones accompanied by unbelievable quantities

of unusual artifacts made of marine shell, exotic stone, bone,

copper, feathers, fabrics, fur, and all manner of materials.

Many of these items represent ritual paraphernalia linked

to the Southern Cult (Southeastern Ceremonial Complex).

As their lease expired and as state authorities

moved to shut down the operation, the Pocola miners tried

to blow up the rest of the mound in a fit of pique. Although

they failed, the damage they had already wrought is one of

the greatest tragedies in American archeology. The whole and

partial artifacts were quickly sold off and wound up in dozens

of museums and private collections around the country. The

1936-1941 WPA archeological excavations by the University

of Oklahoma salvaged many pieces and much information. More

recent work at the site and thorough analyses of the spectacular

collections have made Spiro one of the most important archeological

sites in North America.

Spiro was not an isolated place, but was instead

at the top of a hierarchy of settlements within the Arkansas

Basin—west and north up the Arkansas River and its

tributaries draining the southwestern Ozark Plateau and adjacent

tall-prairies to the west. Related sites are said to occur

within the White River drainage in southernmost Missouri.

During the Harlan phase (A.D. 1000-1250), Spiro was

a ceremonial and population center. After A.D. 1250, the residential

population moved to other sites in the area and Spiro was

used only as ceremonial and mortuary center. The site's role

as a mortuary center peaked in the Norman and Spiro

phases (A.D. 1250-1350 and 1350-1450, respectively). After

A.D. 1450, the site ceased to play an important role in the

region, possibly because east-west trade routes shifted southward

through the Red River valley.

Spiro's wealth is almost certainly a consequence

of its strategic position as a gateway community and

trading center between the Mississippian world to the east

and the Great Plains to the west. Spiro is thought to have

served in much the same way as did St Louis, Missouri in the

18th and 19th centuries: as a crucial hub through which most

east-west commerce and traffic had to pass. In Spiro's case,

the nature and substance of the trade is debated. Some argue

that Spiro was at the center of a trade system that moved

relatively large quantities of economically useful materials

including food, clothing, and weapons. In contrast, other

scholars think that Spiro trade amounted mainly to exchanges

between leaders of ritual items related to the Southern Cult.

The view here is that Spiro trade almost certainly had both

economic and ritual importance.

At Spiro, most of the exotic materials

come either from the local region (including the main Caddo

Homeland to the south) or from distant sources far to the

east. Among the distant sources are those in the Midwest around

Cahokia and across the Southeast, including the Appalachian

Mountains (Tennessee-Kentucky area) and the northeastern Gulf

coast (Florida-Mississippi). It is somewhat less clear what

was moving from the opposite direction from the Great Plains

that would attract this great wealth from the Eastern Woodlands.

Grave145 in Craig Mound had strings of shell beads that had

a total of almost 14,000 beads made from dwarf olive shells

from the Gulf of California. Some of the garments found at

Spiro are made of bison hair, jack rabbit fur, and cotton

fiber. These hint that most of what was moving west-to-east

may have been of perishable material.

Frank Schambach argues that dried bison meat

and bison hides were the principal items moving east from

the Plains. Further, he believes that Spiro also controlled

the trade in bois d'arc wood and finished bows obtained from

the Red River valley in the core of the Caddo Homeland. Bows

and bow wood would have been highly desirable to both the

bison hunters on the Plains as well as the warriors and hunters

of the Mississippian world to the east.

This brings us back to the question of who the

Spiroans were and how they relate to the Caddo groups along

the Red River and elsewhere in the main Caddo Homeland. Although

Spiro and its Arkansas Basin hinterland has long been known

to archeologists as the "Northern Caddoan Area,"

the ethnic/linguistic identity of the Spiroans is debated.

The four possibilities that have been advanced include: the

ancestors of the Caddo, Kitsai, Wichita, and Tunica.

The main reason the debate lingers is because

of the break in the cultural sequence of the Arkansas Basin.

Following the demise of Spiro as an important center by A.D.

1450, the succeeding Ft. Coffee phase (A.D. 1450-1650?)

is said to evidence some cultural continuity with Spiro's

heyday but also changes, such as a shift to circular houses

(from rectangular). Other changes, such as the use of underground

storage pits, are said to reflect a western orientation toward

the Plains. While most authorities think the main east-west

trade routes shifted south through the central part of the

Caddo Homeland, Schambach argues the Spiro area still served

as a gateway community after the demise of the site as a major

center.

By the time French traders entered that part

of the Arkansas Valley in 1719, Spiro was long abandoned and

the area was essentially unoccupied. Farther up the Arkansas

River the French found villages and camps of Wichita and Kitsai

groups, both speakers of Northern Caddoan languages. Yet,

the lifestyle of these peoples as observed by the French was

very different from that of the Spiroans. Were these Northern

Caddoan peoples the descendants of the Spiroans? And what

about the strange people of the province known as Tula that

the De Soto expedition encountered in 1542 somewhere along

the lower or middle Arkansas River?

Parallels between the Arkansas Basin and the

Caddo Homeland to the south have caused generations of archeologists

to believe that the two areas are part of the same "Caddoan"

cultural tradition. This interpretation was built partly

on the finding at Spiro of many finely engraved pots, particularly

of the style named Spiro Engraved, during the WPA excavations

there in 1936-1941. Since the engraved pots are clearly of

the Caddo ceramic tradition and it was assumed that they were

made at Spiro, then Spiro was seen as being part of the Caddo

tradition. But it is now recognized that many of these Caddo-like

pots at Spiro are indeed Caddo pots that come from the main

Caddo Homeland, not the Arkansas Basin. Spiro Engraved, for

instance, was almost certainly manufactured in the valley

of Red River. This realization has done little to alter the

notion that Spiro was part of the Caddo tradition.

The combined region and culture has been called,

variously, the Caddoan Area, the Caddoan Cultural Tradition,

and the Caddoan Mississippian culture based on the assumption

that the entire area was populated by the ancestors of Caddo-speaking

groups. But the obvious dissimilarities (including different

mortuary practices, different dominant house forms, and distinctive

skeletal characteristics) have led to uncertainty about this

all-Caddo notion. Despite many similarities, the Arkansas

Basin cultures were distinct from those in the main Caddo

Homeland for at least 600-800 years (roughly A.D. 800-1600).

Some archeologists believe the parallels between

the two adjacent areas are more important than the differences.

They point to the fact that within the main Caddo homeland

itself there is considerable diversity from local area to

local area. Archeologist Ann Early, who has worked extensively

in the Ouachita Mountains, sees many similarities between

Caddo sites in that area and those in the Arkansas Basin.

For instance, square and rectangular structures (often temples

or other special buildings) are common at Late Caddo sites

in the Ouachita Mountains. (Rectangular buildings are also

found widely farther south in east Texas, but they are vastly

outnumbered by circular structures.) Early and other archeologists

hypothesize that, after the demise of Spiro as a major population

and ritual center in the mid-15th century, the local (presumably

Caddo-speaking) people may have begun migrating south and

east into the nearby Ouachita Mountains.

Or perhaps, as some archeologists have argued,

the Spiroans were the ancestors of one of the tribes that

are closely linguistically related to the Caddo. The Kitsai

and Wichita have been singled out as the most likely

candidates, but not very convincingly so. If these groups

were the descendants of Arkansas Basin peoples, why were their

cultures so different in so many important ways from that

of Spiro? For instance, the Wichita were known throughout

historic times for their round, beehive-shaped grass houses

quite similar to those characteristic of the early historic

Caddo. Yet, Spiro houses were square or rectangular with four-

or two-post central roof supports and an extended entranceway,

a very different architectural tradition. Similarly, Wichita

pottery seems to have been part of the Plains tradition of

cord-marked utilitarian wares, not the engraved fine wares

of the Caddo tradition.

Oklahoma archeologists Charles Rohrbaugh and

Don Wyckoff think a better case may be made for the Kitsai.

They see parallels between the post-Spiro Fort Coffee phase

(ca. A.D. 1450-1600) in the Arkansas Valley and historic village

sites along the Grand River that have been linked to the Kitsai.

Unfortunately, so little is known for sure about the history

of the Kitsai that the Spiro-Kitsai hypothesis has yet to

be confirmed.

The most controversial (and intriguing) suggestion

is that the Spiroans were neither Caddo nor Caddoan, but the

ancestors of the Tunica tribe of the lower Mississippi

Valley. Frank Schambach's hypothesis is that the province

of Tula that De Soto's army attacked in 1542 was at

or near Spiro and that the Tulans were one and the same as

the archeologically known Spiroans. He argues that the descendants

of the Spiroans are the Tunica. From the late 1600s onward

the curious history of the Tunica is well known. The Tunica

were closely allied trading partners with the French and served

as middlemen through which guns and trade goods moved west

in exchange for horses, furs, and hides. They were unequivocally

identified first in the late 1600s on the lower Yazoo River,

just upstream from where the Arkansas meets the Mississippi.

From there they repeatedly moved their villages down the Mississippi

in response to epidemics and trading opportunities.

Schambach's full argument is too complex and

lengthy to be presented here. Basically, he thinks the Tunica

were far more than mere middlemen and were active long-distance

traders who operated a vast trading network during the 18th

century that linked the Southern Plains, the Caddo Homeland,

and the lower Mississippi. This network is said to represent

a continuation or evolution of the one established 600 years

earlier by the ancient Spiroans. Part of the evidence involves

a peculiar type of cranial deformation caused by binding the

heads of infants such that their heads became pointed. The

deformed heads of the people of Tula horrified the Spanish

in 1542. Archeologically this trait is said to be present

at Spiro and at the Sanders site on the Red River, which Schambach

argues was a subsidiary trading center linked to Spiro. It

has yet to be established that the Tunica had this particular

form of deformation, although one French account may suggest

that this was so. Schambach speculates that these grotesque

heads would have given the traders instant recognition, an

advantage when traveling through the territories of other

groups.

While the Tunica hypothesis is fascinating,

it based on a string of tentative inferences that may not

withstand rigorous analysis. Schambach's argument has

not won over the leading researchers who have worked in the

Arkansas Basin. They apparently reject the idea entirely,

but have yet to counter the argument forcefully in print.

The Tunica hypothesis is also rejected out of hand by the

Caddo and Wichita tribes; both tribes claim Spiro as part

of their ancestral realm.

And here is where we will leave the questions

of who the Spiroans were and whether the Arkansas Basin is

truly part of the Caddo Homeland. Unresolved. The view

here is that the problem is a fascinating and important one

worthy of additional research. Schambach's challenge to

the status quo is a very serious one that should be considered

carefully by Spiro scholars, not rejected out of hand. If

a better case can be made for the Kitsai (or the Wichita or

the Caddo), then it should be made with stronger arguments

and better data than has been presented so far. That said,

there may never be enough evidence of the sort needed to make

definitive links between the people who lived at Spiro 600

years ago and living peoples.

Two things are clear regarding the history of

the Caddo peoples. One is that the Arkansas Basin and the

main Caddo Homeland were home to substantially different groups

of people, whether they shared a common ancestry or not.

If the prehistoric peoples of the Arkansas Basin were Caddo-speakers

or speakers of one of the Northern Caddoan languages, they

split from the southern Caddo groups over 1200 years ago.

The other, equally important point is that the two areas

were linked through shared cultural elements and trade for

at least 800 years. There is little or no evidence of

conflict between the peoples of the two areas and much evidence

of trade and the exchange of ideas.

|

Craig Mound as it appeared in 1936

after the "Pocola miners" as the looters called

themselves, were through with it. The destruction of

much of this mound is one of the great tragedies of

American archeology.

Click images to enlarge

|

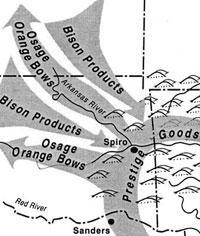

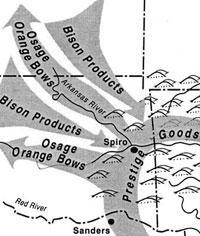

Spiroan trade network in Mississippian

times (about A.D. 1250-1450) as envisioned by Frank

Schambach. This interpretation shows bison products

moving from the Plains east to the Mississippi valley,

while prestige goods moved the opposite direction. Bows

made of Bois d'arc (Osage orange) from the Red River

valley near the Sanders site went both east and west.

Courtesy Frank Schambach.

|

Artist's reconstruction of a large

house based on archeological remains uncovered at House

Mound #5 at Spiro. The grass-thatched roof is supported

by four interior posts. The walls are made of closely

spaced thin poles set within a foundation trench. Daub

(dried mud) plaster sealed the walls. The extended entranceway

helped keep heat from escaping in the winter. This very

large house (9-x-9 meters or 29-x-29 feet) is thought

to have been an elite residence, rather than an ordinary

dwelling. Courtesy Oklahoma Archaeological Society.

|

Embossed copper plate from Craig

Mound, Spiro. The bird figure, identified as a peregrine

falcon, has a distinctive "weeping eye" motif

that appears in many falcon depictions on religious

paraphernalia associated with the Southern Cult. Courtesy

Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural

History, University of Oklahoma.

|

Necklaces of pearl beads from Craig

Mound, Spiro. The pearls were obtained from freshwater

mussels. Large numbers of pearl beads were found in

the mortuary contexts at Spiro. Commercial looters were

said to have amassed two gallons of pearl beads. Courtesy

Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural

History, University of Oklahoma.

|

Marine shell gorgets from Craig Mound,

Spiro, probably made of conch (lightening whelk) from

the northern Gulf coast. These artifacts often bear

elaborate iconography associated with the Southern Cult.

Courtesy Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum

of Natural History, University of Oklahoma.

|

Pipe-smoker effigy pipe made of fine

sandstone, with added white and yellow mineral paint.

The distinctive hair style is identified by James Brown

as characteristic of the shell engraving found at Mississippian

sites in Southern Appalachian and Tennessee-Cumberland

areas. Height and length both about 22 centimeters.

Courtesy Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum

of Natural History, University of Oklahoma. Click to see enlargement and side

view.

|

|

The ethnic/linguistic identity of the Spiroans is

debated. Four possibilities have been advanced: the

ancestors of the Caddo, Wichita, Kitsai, and Tunica.

The problem remains unresolved.

|

Stone earspools from Craig Mound.

Some were originally covered with sheet copper. Courtesy

Robert Bell and the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural

History, University of Oklahoma..

|

|