Aerial view of Battle Mound, the

largest mound in the Caddo Homeland and one of the largest

in the Southeast, measuring some 670 feet in length,

320 feet wide, and 34 feet high. In the background is

the Red River. Photo courtesy Frank Schambach.

|

Stone effigy pipe from the Craig

Mound at Spiro. It has been called "Big Boy"

and "Resting Warrior," but neither of these

labels convey the status that this person—real

or mythical—surely had in the Mississippian world.

The figure may represent the mythical character known

as Red Horn among many historic Indian groups (see opposite

panel).

The pipe is made from red flint clay mined near Cahokia.

Recently, it has been hypothesized that this sacred

object and others like it were made in the 12th century

and used at Cahokia. When the power of that great site

waned in the late 13th century, important sacred objects

like this pipe were taken to other sites like Spiro

and Gahagan.

The seated figure wears a pair of long-nosed god mask

earrings. On his back is a feathered cape, similar to

those found in fragmentary condition at Spiro. Around

his neck are heavy strings of beads. On his head is

a curious cap that archeologist James Brown believes

served to display embossed copper plates. (26 centimeters

high or about 10 inches.) From the collections of the

University Museum, University of

Arkansas. Photo courtesy Pictures of Record.

|

"Bird-man" depicted on

a repoussé copper plate from the Etowah site,

Georgia. (Repoussé is a technique used to create

raised designs by hammering a thin metal sheet from

its back.) In this example the bird-man seems to be

a human dancer wearing a falcon costume. A human head

appears to be dangling by its scalp from the bird-man's

left hand. Bird-man figures are a common representation

in Mississippian ritual art.

|

This wooden statue from Craig Mound

at Spiro may be a representation of an ancestor like

those seen by early European visitors in temples and

charnel houses in the Southeastern U.S. (32.5 centimeters

high) Smithsonian Institution.

|

Conch shell gorget from the Sanders

site in the Red River Valley in Lamar County, Texas.

The depiction of severed human heads is a common theme

in Mississippian symbolism. The Sanders site dates mainly

to the Middle Caddo period, about A.D. 1200-1400, and

seems to have had a special relationship with Spiro,

the nature of which is debated. More Southern Cult objects

are known from the Sanders site than any other Caddo

center south of Spiro. TARL archives.

|

|

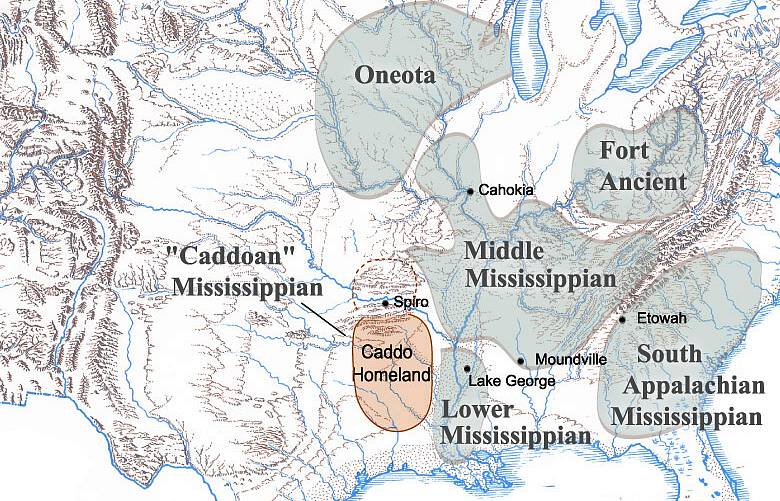

Among the hundreds of ritual centers across

the Mississippian world, most were relatively small and contained

only a few mounds. A few among them stood out as primate

centers. These places were the biggest of the big, the

political and ritual centers of complex and unusually successful

chiefdoms. The largest and most powerful of them all was the

Cahokia site in the central Mississippi Valley near present

day St. Louis. Cahokia had perhaps 200 earthen mounds and

may have been home to as many as 15,000 people at its height

around A.D. 1150. To the southeast were Moundville, in northern

Alabama, and Etowah, in northern Georgia, both the largest

sites in their local regions and both peaking 100-150 years

after Cahokia. In the lower Mississippi Valley, the sites

of Winterville and Lake George had dozens of mounds and were

larger than all others in the region. The westernmost major

center was the site of Spiro in the Arkansas Valley.

The best candidate for a primate center in the

main Caddo Homeland is the Battle site in southwest Arkansas

in the Great Bend area of the Red. This site contains the

largest mound in the Caddo Homeland and one of the largest

in the Southeast, measuring some 670 feet in length, 320 feet

wide, and 34 feet high. The only other known mounds at the

Battle site were four very low rises (now leveled for agriculture),

but there are numerous cemeteries, occupation areas, and mounds

in the general vicinity that may well have been part of the

greater Battle community. Unfortunately, the site has only

seen minor investigation and remains little known. The absence

of obvious primate centers in the main Caddo Homeland may

reflect, at least in part, the nature of Caddo settlement

patterns: people lived in dispersed communities more often

than nucleated villages. There are numerous smaller ritual

centers in the Caddo Homeland that probably served as the

central places of small, independent polities (political units)

that some would call chiefdoms.

Although never politically united, the Mississippian

world was united in a cultural sense by participation in widespread

religious and social phenomena often described as "cults."

This is perhaps a poor choice of terms as the word cult may

conjure up images of small extremist groups. Mississippian

"cults" were part of very powerful and widespread

religious movements that we are only beginning to understand.

The best-known Mississippian religious movement

is popularly known as the Southern Cult, although most

archeologists today prefer the less evocative phrase Southeastern

Ceremonial Complex. The central tenets of this cult or

religion were transmitted through rituals and through the

exchange of sacred objects emblazoned with symbols such as

falcons, crosses, and rattlesnakes. Often the iconography

depicts scenes of violence and warfare, such as warrior figures

holding weapons and decapitated heads. These symbols were

carved, modeled, engraved, and painted on many materials,

most of them probably perishable (like cloth and wood) or

made from exotic materials, such as copper and marine shell,

imported from distant sources.

The Southern Cult was exclusive—only certain

individuals and kin groups participated, thus supporting the

authority of the chiefs. They alone could handle, wear, and

own the most sacred symbols, which were no doubt perceived

as possessing power and being too dangerous for any but the

chosen few to handle. When the leaders died, the cult artifacts

were buried with them, perhaps to protect the people from

danger. (Or, to take a more pragmatic interpretation, to keep

such symbols out of general circulation, and thus rare and

more prestigious.) By exchanging these symbolic artifacts

among one another, the leaders also maintained trading and

political alliances. Such alliances were important because

warfare appears to have been widespread.

Among the Southern Cult artifacts that do survive,

carved marine shell gorgets (chest ornaments) and drinking

cups, are the most widely distributed. Many shell ritual objects

were made from lightning whelk shells from the northern Gulf

coast. The cups were used in rituals during which participants

consumed the famous "black drink," a dark tea made

from yaupon leaves. Much misinformation exists about the black

drink. Its principal active ingredient is caffeine. Early

European visitors to the Southeast were appalled when they

witnessed what could be called "projectile vomiting"

during rituals involving the consumption of the black drink.

This purposeful ritual purging or cleansing was induced by

drinking lots of hot tea quickly, not by the properties of

the tea. Yaupon bears the scientific name Ilex vomitoria,

a name born out of European misunderstanding.

There is also good evidence for the existence

of a widespread Earth Cult (for lack of a better term)

that was tied to renewal, fertility, and the periodic building

of earthen mounds. This set of beliefs was communal in nature

and served to bring people together to participate in community-wide

rituals. Periodically, temples and other special buildings

were carefully dismantled or burned and buried with a fresh

layer of earth, often chosen for its color and texture. Burial

mounds received similar treatment: periodic renewal by the

addition of new layers of earth.

Some archeologists, including Dee Ann Story

and Frank Schambach, think that for the Caddo what was most

important was not the mounding of earth, per se, but what

the earth was mounded over—ritually destroyed temples

and tombs. Referring to the burning of temples, Schambach

believes that "for the Caddo, one immediate objective

of this ritual may have been to produce the great plume of

smoke and steam that must have emanated from each burned and

buried building for days or even weeks, as a cord or more

of wood was slowly reduced to charcoal." He reasons that,

to the Caddo, fire and smoke were the key elements,

not earth, an idea that finds support in early historic accounts

of the importance of fire to Caddo groups.

Earth, fire, or smoke, the timing of such ritual

activities was probably tied to the agricultural cycle and

perhaps to longer ritual cycles linked to the death of important

chiefs or astronomical phenomena. Major ritual events almost

certainly included feasting, dancing, and other communal activities.

The third widely shared religious practice was

Ancestor Veneration. Showing respect for exalted ancestors

took many forms, including elaborate burials such as the shaft

tombs of the Caddo and mounds where only certain members of

society were buried. Most Caddo groups were unusual among

Mississippian societies in that they buried their dead quickly

while their bodies were still intact. Most other societies

in the Eastern Woodlands had charnel houses where bodies were

stored until the flesh had rotted (or had been removed by

priests) and only bones were left. Periodically, the charnel

houses were cleaned out and the accumulated bones buried together

during elaborate rituals, perhaps also linked to renewal.

Another widespread indication of ancestor worship is the existence

of temples containing human statues made of stone or wood

and some times sacred bundles or boxes containing the bones

of a revered ancestor or special ritual items. These are best

known from the accounts of early European explorers, although

human statues made out of wood, ceramics, and stone have been

found at Spiro and other Mississippian sites.

Mississippian iconography often seems to glorify

war and victory over vanquished foe. But as far as we can

tell, most Mississippian warfare was more akin to raiding

or ritual warfare, rather than all-out conquest. Most conflicts

were probably raids to kill or capture warriors for revenge

or arranged battles of limited scope. Nonetheless, the presence

of fortified towns, particularly in the Mississippi Valley,

suggests that people had reason to fear. Warrior motifs are

often found on the engraved shells and other symbolic artifacts.

Armed figures holding human head and scenes of decapitation

and human sacrifice leave little doubt that military victories

were glorified. Unambiguous archeological evidence of ritual

cannibalism support eyewitness accounts of early explorers.

Mississippian life was sometimes violent and gruesome.

The Caddo Homeland was on the geographical and

cultural edge of the Mississippian world. As far as we can

tell, ancestral Caddo groups never established large, complex

chiefdoms, with the possible exception of Spiro. Instead the

Caddo world was one of relatively small-scale chiefdoms of

the sort described by the Spanish and French chroniclers.

The largest Caddo centers had less than a dozen mounds, usually

far less. With the notable exception of Battle Mound, most

Caddo earthworks are small by comparison to those at major

Mississippian centers, and tiny by comparison to Cahokia.

Caddo centers were also laid out less formally and more organically

than major Mississippian centers and they lacked fortifications.

What accounts for these differences? The location

of the Caddo Homeland on the western frontier of the Eastern

Woodlands is clearly a major factor. Most of the river valleys

of the Caddo Homeland pale in size and productivity in comparison

to the Mississippi and its major tributaries where many of

the Mississippian developments took place. It is no accident

that the largest and most complex Mississippian society developed

at Cahokia in the central Mississippi valley. In the same

way, Spiro is in the Arkansas Valley and, to the south, most

of the larger Caddo centers occur along in the Great Bend

region of the Red River, the largest and most fertile of the

waterways in the main Caddo Homeland. Another consequence

of being on the Mississippian frontier is that Caddo groups

did not have any neighboring competing chiefdoms to contend

with (at least to the west), which probably helps explain

why Caddo sites were not fortified.

The other major factor seems to have been the

nature of Caddo societies themselves. Caddo societies seem

to have split apart before becoming too large. We can speculate

that Caddo societies developed mechanisms for sharing food

and wealth and for "social leveling" — keeping

high and low ranking classes (or clans) from being too segregated.

Rigid caste-like social classes like those of the Natchez

do not appear to have existed among the historic Caddo. Still,

Caddo societies were not egalitarian; they had marked social

inequalities as described in early historic accounts, and

seen in differences in house size and location within archeological

sites, in differences in comparative size and wealth among

sites, and in differences in grave elaboration.

|

Battle Mound, the largest known Caddo

mound, is in southwest Arkansas. Note person standing

in front of tree-covered mound. Photo courtesy Tim Perttula.

|

Long-nosed god mask earring from

the Gahagan Mound site in northwest Louisiana. One of

a matched pair found within a mass of artifacts in the

corner of an Early Caddo tomb, the earring is made of

sheet copper. The pair probably represent ritual ear

ornaments as depicted on the effigy pipe from Spiro

shown opposite.

Long-nosed god depictions are known from many North

American and Mesoamerican cultures. Anthropologist Robert

Hall has linked the Mississippian-period long-nosed

god with the mythical figure known as Red Horn or He-who-wears-human-heads-as-earrings

to the historic Winnebago and Iowa Indians of the upper

Midwest. Hall believes the mask earrings were part of

adoption rituals in Mississippian society during which

important leaders extended fictive kinship bonds to

visiting leaders, thus cementing political alliances.

Photo courtesy Pictures of Record.

|

Marine shell (lightning whelk) drinking

cup from cemetery burial at the Haley site on the Red

River in southwest Arkansas. In Mississippian societies,

shell drinking cups were used in rituals during which

participants consumed the famous "black drink,"

a dark, caffeine-rich tea made from yaupon leaves. Photo

courtesy Pictures of Record.

|

Cross-section through a temple mound

at the Ferguson site, a Late Caddo site dating to about

A.D. 1400 that is located in the Little Missouri River

Valley in southwest Arkansas. The burned layers near

the bottom of the picture are the remains of a small

temple that was purposefully collapsed, then burned

and intentionally buried. Photograph courtesy of Pictures

of Record.

|

|

The Mississippian world was never uniform or united;

instead it was fragmented and fractious, a 600-year

era during which dozens of chiefdoms arose and then

fell apart.

|

Artist's depiction of a dispersed

Caddo settlement in what is today southeastern Arkansas.

The house on the rectangular earthen mound in the foreground

is that of a chief or shaman; the mound caps the remains

of earlier houses of important people. Scattered in

the background are family compounds, some with both

winter (rectangular) and summer (round) houses as well

as raised storage bins where surplus corn was stored.

All of the details are based on archeological and historical

evidence. Courtesy Arkansas Archeological Survey.

|

|