"Among the seed

which the Indians plant at the proper season, is corn

of two kinds, which they plant in abundance. One kind

matures in a month and a half and the other in three months."

-Spanish priest Fray Casañas, 1691. |

Dried beans in an ancient Caddo bowl.

The Caddo grew five or six varieties of beans according

to Fray Casaņas, a Spanish priest who lived among the

Hasinai Caddo in 1691. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

White-tailed deer were the favored

prey for Caddo hunters and the main source of meat throughout

Caddo history. Deer hunts were preceded by special ceremonies

involving deer heads and skins. Courtesy Texas Parks

and Wildlife Department.

|

The American persimmon tree, Diospyros

virginiana, grows in much of the Eastern United States

including the Caddo Homeland. Its astringent fruit ripens

in the fall and becomes sweet and quite delicious when

fully ripe and after the first frost. Photograph by

Frank Schambach.

|

Soft-shelled turtles and other aquatic

critters and fish were part of the diet of those Caddos

lived near rivers and larger streams. Courtesy Texas

Parks and Wildlife.

|

Sunflowers were an important seed

crop and one of the plants domesticated in the Eastern

United states. Early Spanish explorers were surprised

by the size of the giant sunflower heads the Caddo grew.

Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

Pumpkins were grown and savored by

the Caddo and their Wichita cousins. Like their close

relative, the winter squash, pumpkins were cut into

strips and dried. The strips were woven into crude mats

for easy transportation and storage. Photograph by Frank

Schambach.

|

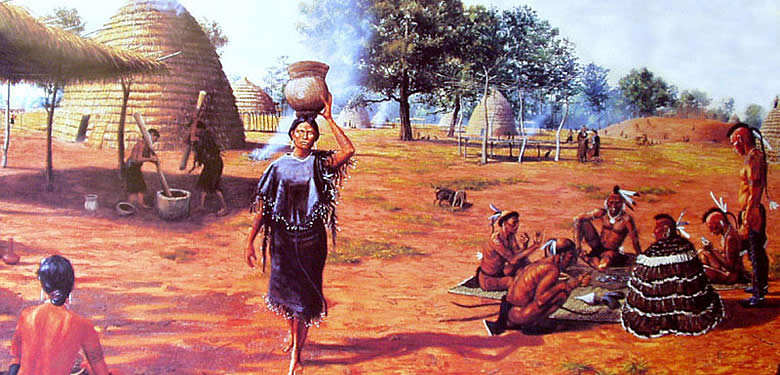

Artist Ed Martin's depiction of salt-making

scene based on historic accounts and archeological evidence

from the Ouachita Valley in Arkansas. Caddo groups who

lived near natural seeps of highly salty water called

salines collected the salt by evaporating the water.

In 1700, French explorers encountered Ouachita Caddos

paddling canoes laden with salt on the lower Red River

on their way to trade with the Taensa people living

in the lower Mississppi Valley. Courtesy Arkansas Archeological

Survey.

|

Bois d'arc or Osage orange tree in

late fall. Its fruits are inedible to humans and most

animals but horses love them, hence the name "horse

apple." According to evolutionary biologists, only

a small relic population of Bois d'arc trees survived

after the end of the last Ice Age. The tree does not

compete well with other trees and it needs large herbivores

like horses or mammoths to spread the seeds. When Europeans

reintroduced horses to North America in the 16th century,

the tree spread quickly aided by farming practices.

Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

This Caddo dugout canoe was found

washing out of the base of a steep bluff on the Red

River in northwest Louisiana. It has been radiocarbon

dated to about A.D. 1000. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

Late Caddo ceramic pipe bowls from

the A.C. Saunders site in northeast Texas. Wooden or

bone stems were added to such pipe bowls. Tobacco was

grown by the Caddo and was used in both ritual and ordinary

settings. The Caddo greeted early Spanish and French

visitors with the calumet or smoking-pipe ceremony as

was common among many Southeast and Plains groups. TARL

archives.

|

This hawk wing and peacock feather

dance fan is a modern example of a very old Caddo tradition—the

making of ritual and dance paraphernalia. Maker unknown,

c. 1970, in the Claude Medford, Jr., Collection., Williamson

Museum, Northwestern State University, Nachitoches.

Photo by Dayna Bowker Lee.

|

This thatched hut in the Yucatan

of Mexico was constructed using traditional techniques

very similar to those used by Caddo groups in the northern

Caddo Homeland. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

|

Caddo Economy

The first Spanish and French visitors to the

Caddo Homeland encountered thriving communities whose livelihood

was based on farming, hunting, gathering, and trade. Archeological

evidence indicates that a mixed economy was characteristic

of Caddo ancestors for at least a thousand years, probably

much longer. Most accounts of Caddo life emphasize agriculture

and rightly so because farming provided much of the dependable

food supply upon which village life depended. The central

role played by farming also helps explain why Caddo settlements

characteristically were scattered and spread out—the

Caddo lived among their fields and gardens.

In historic times, corn (also called

maize) was the mainstay crop. The Caddo grew several varieties

of corn including "little" corn that ripened in

the summer and "flour" or "great" corn

that ripened in the fall. Corn was dried on the cob and stored

in raised granaries to keep it dry and protected from rodents.

The Spanish noticed that the Caddo always saved their best

corn for seed and hung the seed corn cobs high inside their

houses where it would not be touched except for planting,

no matter how little food was available. Corn also figured

prominently in the annual ritual cycle with planting ceremonies,

first-fruit or green corn ceremonies, and harvest rites. Successful

fall harvests occasioned major festivals at the principal

villages. These drew kinfolk and allies near and far for several-day

celebration of Caddo life: feasting, tobacco-smoking, black-tea-drinking,

dancing, trading, negotiating, courtship, and more.

Other important crops included beans (five or

six varieties according to Fray Casañas, the Spanish

priest who lived among the Hasinai in 1691), squash, pumpkins,

sunflowers, and various lesser-known domesticated plants including

goosefoot (Chenopodium sp.). The Caddo quickly adopted crops

introduced by the Europeans, including watermelon and peaches.

Tobacco was another important crop required for ritual use.

Women did most of the farming and all of the food preparation,

although men did some heavy work such as clearing fields and

helped at critical times such as harvest. Farming was also

very much a communal activity. Fields were owned by the community

and families were assigned specific plots by the tammas. Planting

and harvesting were community projects that moved from plot

to plot beginning with that of the xinesi and moving down

the social ladder until each family plot had been reached.

Wild plants, game, and fish were also vital

food resources. Wild plants included nuts (hickory, walnut,

acorn, and pecan), berries, plums, persimmon, grapes, and

various seed plants, just to name a few. Throughout most of

Caddo history, the favorite game animal hunted by Caddo men

was the white-tailed deer. Deer provided most of the

meat as well as hides, antlers, sinew, and bones for tools

and clothing. Deer also figured prominently in Caddo dance

and symbolism. Buffalo were hunted on extended trips west

or northwest out onto the prairie-plains, but were not an

important food source until after the late 17th century after

the Caddo acquired horses. Turkeys, rabbits, and various other

small animals and birds were hunted and snared. Caddo living

along productive waters caught fish, turtles, and other aquatic

species. Bear were hunted for food, fur, and especially for

their fat, which served many useful purposes and was traded

to the French.

Three factors seem to underlie the long-term

success of the Caddo economy: diverse natural resources,

well-developed food processing and storage technologies, and

the ready adoption of new crops from their neighbors and

trading partners. Caddo peoples relied on many different wild

and cultivated food resources, of which only a few have been

mentioned. These changed in importance from place to place

and with the seasons, the vagaries of rainfall, and through

time. When crops failed, the Caddo turned to wild plant foods

that had been used for generations.

They had many ways of storing food to

get them through the annual low point in resource availability:

winter and early spring. They dried corn, beans, pumpkins,

wild fruits, and deer meat. They smoked fish and other meats.

They built raised and tightly sealed granaries to keep their

corn supplies dry and vermin-free. Along the Red River west

of the Great Bend, some Caddo groups used underground storage

pits similar to those used by their Plains neighbors. From

river cane and certain barks and grasses, Caddo women wove

baskets and trays large and small, tight or loose; some for

storage, others for winnowing and sieving. Out of clay they

created all manner of ceramic cooking, storage, and serving

containers. Bear fat, for instance, was rendered and stored

in clay pots. Through such methods the Caddo survived thick

times and thin.

Agriculture was central to Caddo life when Caddo

communities were first visited by Europeans, but this was not

always the case. Early Caddo ancestors were hunters, gatherers,

and fishers, living off the land. By 2,000 years ago,

if not well before, ancestral Caddo groups began to cultivate

the starchy and oily seeded plants that had been domesticated

in the Eastern Woodlands by about 2000 B.C. We aren't certain

when this happened because few plant remains of any sort have

been recovered from the excavated Woodland sites in the Caddo

Homeland. But there is little reason to doubt that native

crops, including goosefoot, marsh elder, squash, and possibly

sunflower, were adopted early on by the Caddo.

At first these native seed plants would have

been mere supplements to hunting and gathering, but along

with gardening comes the requirement of returning to fixed

places to plant, harvest, process, and store. The native seed

crops were probably sown broadly in minimally cleared plots

and allowed to compete with weeds. The real labor was in the

harvest and processing; only the sunflower had compact durable

seed heads. Goosefoot and marsh elder had small seeds and

friable seed heads. All had to be carefully cleaned and separated

from the stalks and chaff. These native seeds tasted bland

and were probably prepared mainly in stews and gruels. Gradually,

farming became more important, but was probably still secondary

to hunting and gathering for centuries. Even though early

farming must have provided only a small, labor-intensive part

of the diet, the ability to produce this extra food and the

requirement to stay nearby while it grew may have been the

critical factors that led to increasingly settled village

life.

Later, we aren't sure exactly when, the Caddo

adopted a tropical plant that had been domesticated in Mesoamerica

and already adopted by farming peoples in the American Southwest:

corn. Corn first appears at Caddo sites around A.D. 800,

but may not have become a mainstay of the economies of most

groups until after A.D. 1100. The reason for this lag is unknown,

but a similar pattern occurred elsewhere in the Southeast,

including the lower Mississippi valley. By 800 years ago (A.D.

1200), the Caddo were big-time corn farmers who also grew

squash/pumpkins, beans, sunflowers, and various other crops.

Corn had to be planted seed by seed in individual

holes and required greater effort to clear the land, keep

it weeded, and fend off animals and birds. But the payoff

came at harvest time when whole stalks could be broken off

and gathered quickly, each containing one or two fat seed

heads (cobs). (Corn was harvested stalks and all because the

stalks were useful fuel for cooking fires.) Compared to the

native seed crops, corn required minimal cleaning and processing

and, once dried, could be readily stored without husking or

stripping.

Perhaps even more important was the fact that

corn tasted sweet and flavorful, and it could be prepared

in many more ways than the native crops: raw, parched, roasted,

steamed, boiled, ground into flour, and more. Small wonder

that corn became the economic lynchpin of Caddo life, celebrated

in song and ritual, and symbolically linked to the sun,

the giver of life. There was a downside; eating lots of corn

caused a noticeable increase in caries (cavities).

Trade was also an important part of the

Caddo economy, at least in historic times. Caddo groups traded

resources found within the Caddo Homeland among each other

and to outside groups. The best-known Caddo trade goods were

bois d'arc wood and salt. Salt was obtained in various places

in the Caddo Homeland where saltwater springs or seeps were

present. Caddo salt workers concentrated the salt brine by

evaporation and boiling in heavy pottery pans and then traded

the dried salt to groups elsewhere. For instance, in the spring

of 1700, French explorers encountered Ouachita Caddos paddling

canoes laden with salt along lower Red River, on their way

to trade with Taensa peoples living along the Mississippi.

Bois d'arc (Osage orange) bow wood blanks and

finished bows from the Caddo Homeland were traded for hundreds

of miles east and west. Bois d'arc is the best bow wood

found east of the Rockies and the Cadohadacho groups may

have had a monopoly on it. By late prehistoric times the natural

range of bois d'arc apparently was restricted mainly to a

small area along and south of Red River valley, just upstream

from Texarkana.

Bois d'arc does not grow well among other trees

and evolved to rely on large herbivores like horses or mammoths

to spread its seeds to open areas; most other species, including

humans, find the horse apple, as its fruit is known, inedible.

At the end of the last Ice Age about 12,000 years ago, horses

and mammoths became extinct in North America, leaving the

bois d'arc without a natural means of spreading. By the time

Europeans arrived, the main remnant bois d'arc population

grew within the western Caddo Homeland at the edge of the

Blackland Prairie. The reintroduction of horses and Anglo-American

farming practices allowed the bois d'arc to spread quickly

over a wide area of the south-central U.S. Farmers planted

bois d'arc along fence rows, were it is still principally

found today.

The role of the bow-wood trade in Caddo history

has recently become the subject of debate. Arkansas

archeologist Frank Schambach has put forth the intriguing

argument that, prior to the historic period, the bow-wood

trade was controlled by Mississippian traders (ancestral Tunica)

from Spiro who established trading posts within the Caddo

Homeland. The idea that foreign, non-Caddo intruders controlled

enclaves within Caddo territory, such as the Sanders site

on the Red River in Lamar County, has not been accepted by

many Caddo scholars (nor by the Caddo Nation). For instance,

the state archeologists of both Arkansas (Ann Early) and Oklahoma

(Robert Brooks) have taken issue with Schambach's argument.

This controversial interpretation and arguments pro and con

will be the subject of a future exhibit on Texas Beyond

History.

Regardless of who controlled the bow-wood trade,

trade may well have played a greater role in Caddo history

than has been recognized. The Caddo Homeland is, after

all, located between the Southeast and the Plains as well

as the Southwest, three major culture areas and ecological

zones with very different natural resources. Dried buffalo

meat and buffalo hides from the Plains were traded widely

in early historic times, as were salt, bow wood, and artifacts

made of Gulf of Mexico shells from the Southeast, as well

as cotton, turquoise, and shell artifacts from the Gulf of

California from the Southwest. The spectacular wealth entombed

in the Craig Mound at Spiro (about A.D. 1350-1450) is almost

certainly a product of an earlier east-west trade system and

there are many reasons to suspect that the Caddo groups to

the south were also major players, particularly in the centuries

following the demise of Spiro as a major center. In the early

18th century, the French quickly enlisted the Caddo as trading

partners to take advantage of their strategic position and

established reputation as trustworthy middlemen.

Caddo Ritual and Religion

In the late 17th century the Hasinai were said

to believe in a supreme god called the Caddi Ayo or

Ayo-Caddi-Aymay, sometimes translated as "captain

of the sky." The Caddi Ayo was believed to be the creator

of all things and was held in great deference. The natural

world of the Caddo was, however, inhabited by many other kinds

of spirits including those personified by animals, places,

and forces of nature. The Caddo followed many ritual practices

in order to keep things right in their world. Matters religious

were organized in a hierarchal fashion parallel to those that

ordered society.

The xinesi or head priest lived in a

special precinct within the Hainai (chief Hasinai group) community

or, after the early 1700s, in a separate place between the

Neche and Hainai communities. Either way, the xinesi lived

in a large grass-thatched house that stood near the fire temple,

the principal Hasinai temple within which burned a perpetual

fire fed by four logs, each oriented on a cardinal direction.

Among the xinesi's chief responsibilities was keeping the

fire going. There were apparently other, lesser fire temples

among the Hainai groups, watched over by lesser priests or

by the caddis. Similar temples were also described among the

Cadohadacho and, archeological evidences suggests this was

a widespread and old Caddo practice.

The Hasinai fire temple was a very large

structure that also served as a council house where important

matters were decided. Nearby was one or two small houses where

two divine boys (possibly twins) called the coninisí

lived. These children served as intermediaries between the

xinesi and the Caddi Ayo and were only visible to the xinesi,

a circumstance that the Spanish priests ridiculed and cited

as proof of the false nature of Caddo religion. Nonetheless,

belief in the coninisi was widespread and they are may be

analogous to the hero twins found in many other Native American

religions.

The xinesi was aided by other priests or shamans,

some of whom carried out similar duties for individual communities

and some of whom had specialized assignments. While most priests

were men, there were apparently some women as well. The Spanish

accounts are not clear on how the Caddo priesthood was organized,

in part because priests on both sides saw the others, quite

correctly, as dangerous competitors who challenged their own

domains.

Caddo life was seen as dependent on the proper

performance of rituals small and large for continued success.

There were proper and wrong ways of doing all things of substance.

For instance, hunters sought a priest on the eve of a deer

hunt to perform elaborate rituals involving the head and horns

of a deer. If successful, the deer could not be butchered

and eaten until a priest had whispered into its ear and taken

the first share of meat. Similarly important rituals were

associated with agriculture. Young and old women took part

in a special spring ritual prior to planting to ensure good

crops. There were also first fruit or green corn ceremonies

and harvest ceremonies, each being the occasion for feasting

as well as ritual.

The connas, the Caddo medicine men or

healers, were said to use herbs and various ritual practices

such as smoking, sweating, incantations, and divination to

cure sickness and heal the wounded. While the Spanish were

distrustful of the medicine men, they also observed successful

healing and realized that some of the herbal remedies were

potent. Many of the curing ceremonies involved practices the

Spanish associated with the devil. The Spanish priest Espinosa

as translated by Bolton describes one such event.

To cure a patient they make a large fire

[under the bed] and "provide flutes and a feather fan.

The instruments [palillos] are manufactured [sticks] with

notches resembling a snake's rattle. This palillo [rasp]

placed in a hollow bone upon a skin makes a noise nothing

less than devilish. Before touching it they drink their

herbs boiled and covered with much foam and begin to perform

their dance without moving from one spot, accompanied by

the music of Infierno, or song of the damned, for only in

Inferno will the discordant gibberish which the quack sets

up find its like. This ceremony lasts from midafternoon

to nearly sunrise. The quack interpolates his song by applying

his cruel medicaments.

It is unlikely that the medical practices of

17th century Europe would be viewed by us today as any more

sound or less superstitious than that of the 17th century

Caddo. The Spanish and French witnessed and sometimes harshly

described a Caddo society that had a complex and quite sophisticated

set of beliefs and practices about the natural and supernatural

world. It is only to be expected that the two worlds were

foreign to one another and that neither side really understood

the other.

|

Heirloom varieties of "Indian

corn" thought to be similar to those grown by Caddo

ancestors. The top ear is 7.5 inches long (19 centimeters).

Photograph from Richard I. Ford, courtesy Dee Ann Story.

|

Hickory nuts were an important food

throughout Caddo history and probably long before. These

tough-shelled nuts were high in fat and protein, but

difficult to shell. Pitted "nutting" stones,

such as those shown here, are found in Archaic, Woodland,

and Caddo sites. Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

Wild turkey in piney woods of southeastern

Arkansas. Turkeys were hunted for their meat and feathers.

The turkey also inspired the famous Turkey Dance, a

Caddo favorite. Photo by Bill Martin.

|

Ripe American persimmons were a fall

treat for the Caddo and were used in a variety of ways.

In early fall, persimmons are very astringent, causing

the mouth to pucker. But when fully ripe and after the

first freeze they become sweet and tasty. Dried persimmons

could be stored for months. Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

Muscadine grapes grow plentifully

in much of the Caddo homeland. Although very tart, they

could be gathered in large quantities in late summer.

Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

Winter squash similar to this butternut

squash was a favorite Caddo crop. The thick-fleshed

squash could be cut into strips and dried, similar to

pumpkins. Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

Wild plums (Prunas sp.) were a seasonal

delight for the Caddo. These tart but nutrious fruits

could be harvested in large quantities in late spring

during good years when rains came at the right times.

Some were eaten fresh, but most were mixed with other

foods, such as stews and pemmican, or dried for later

use. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

Bois d'arc wood, one of the best

bow-making woods in North America, was traded far and

wide from its only source, a small area of the Caddo

Homeland near the Red River above the Great Bend. Photograph

by Frank Schambach.

|

Artist Reeda Peel's depiction of

a Caddo woman carrying a basket of freshly picked corn.

Corn became the Caddo's mainstay crop about 800 years

ago and was considered a sacred plant because of its

importance to Caddo life. Courtesy of the artist.

|

Native river cane once grew profusely

along streams and rivers in the Caddo Homeland. Today

it has largely been replaced by an exotic species of

Asian cane. Cane was put to many uses including house

building and for weaving. The Caddo were famous for

their split cane mats and baskets. Photograph by Elizabeth

Stoker, courtesy Frank Schambach.

|

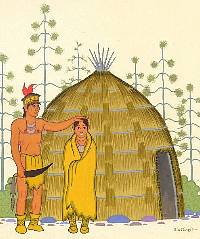

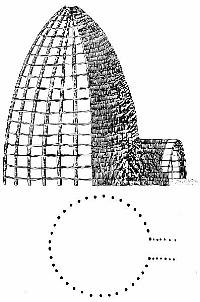

In the southern Caddo Homeland, tall

grass-thatched houses with circular outlines were the

most common form. Extended entranceways, as shown in

this diagram, were often associated with larger buildings

thought to be the residences of important people. Courtesy

Frank Schambach.

|

This split-cane mat, made by the

late Claude Medford, Jr. (Choctaw), is probably very

similar to those for which the Caddo were well known.

Courtesy Frank Schambach.

|

|