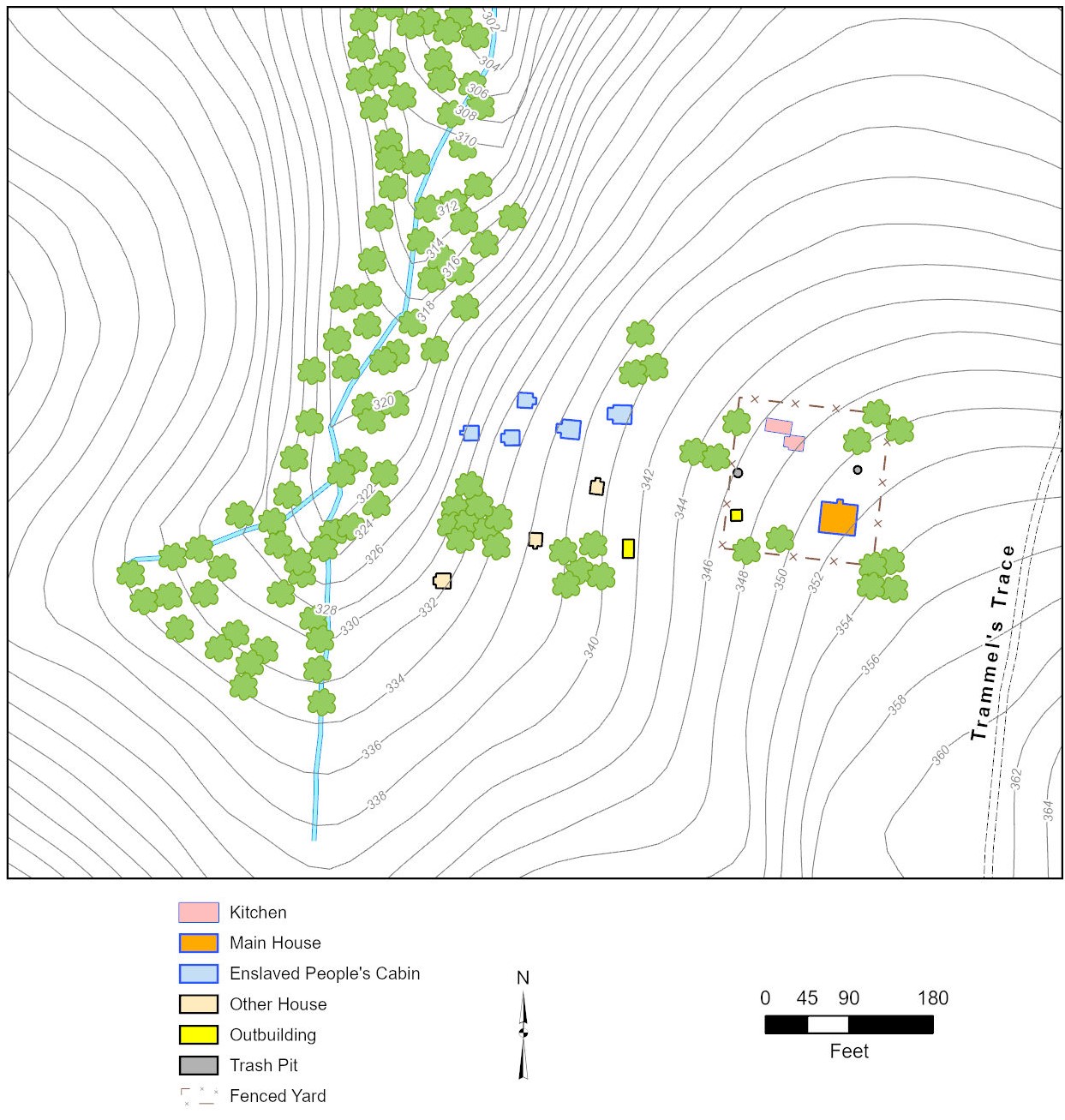

An exceptional attribute of the Hendrick plantation archeology is that archeologists know the locations and uses of the many buildings that made up the residential core. These included the "big house" where the Hendricks lived, the detached kitchen to the northwest where the enslaved cook prepared meals for the Hendricks and perhaps sometimes for other enslaved people, five cabins downslope to the west where the enslaved lived and where freedmen may have stayed after Emancipation, and three cabins nearby where archeologists think non-enslaved people lived. This latter group probably varied over time, but researchers know that Seaborn Hendrick Sr.’s widowed mother lived at the plantation, reportedly in her own house, from 1854 to 1869. Additionally, the 1860 census lists a 65-year-old farmer and 22-year-old schoolteacher as living on the plantation.

With this knowledge, archeologists used the artifacts they found to address questions about how the lives of the Hendricks and the people they enslaved were similar or different. For example, differences in the sizes of the nails found indicate that the big house and kitchen could have had plank siding and thus looked different than the other buildings, but all of them were similar in that they were mostly of log construction with plank floors and shake roofs. Of course, the big house was much larger than any of the others, and its mostly brick chimney set it apart from the stone kitchen chimney and mudcat (mud and wood) chimneys at the cabins of the enslaved. The house also had far more glass-paned windows than any of the other buildings, but archeologists found window glass at all the smaller dwellings as well, indicating that each had at least one glass-paned window.

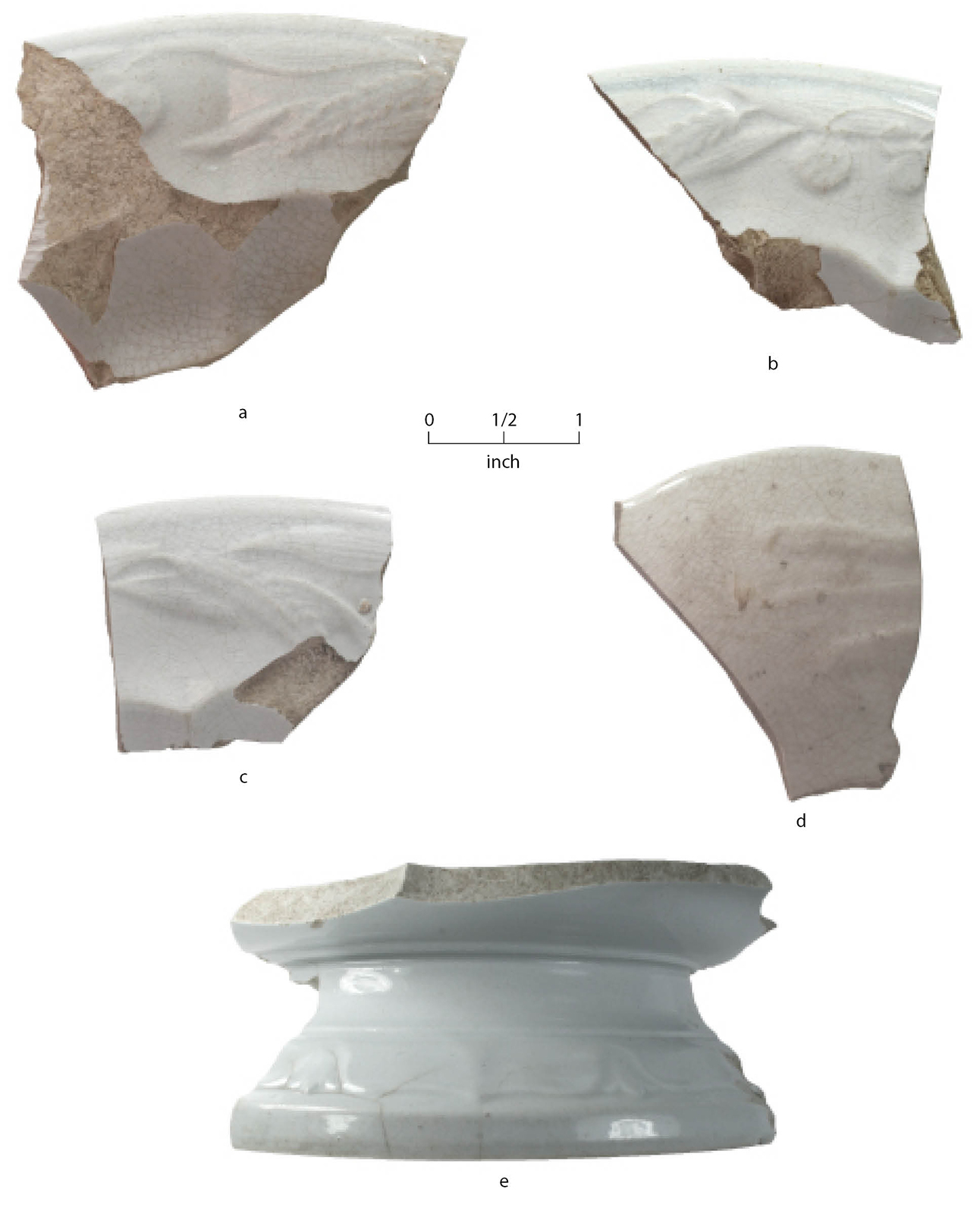

Other than the many thousands of nails and pieces of window glass left over when the big house collapsed after it was abandoned, artifacts were scarce at and immediately around this building, indicating that the yard around the house likely was swept clean. The enslaved African Americans responsible for this chore disposed of the trash in pits they dug around the edges of the yard. The archeologists found and excavated two of these pits, but others probably remain undetected. The scarcity of artifacts in the big house excavations made it hard to see direct evidence of the activities the Hendrick family engaged in there, but archeologists did recover items relating to repairing horse tack, some firearms cartridge cases and pieces of lead shot, a variety hardware fragments like hinges and screws, four pieces of a children’s tea set, clothing buttons, fragments of shoe soles, sherds of porcelain and white granite ceramic plates and other dishes, fragments of pressed glass tumblers, sherds of stoneware jars and crocks, oil lamp parts, sherds of various kinds of bottles, a blacksmith hammer head, a couple of cotton bale wire ties, a fragment from a writing slate, a glass bead from a piece of jewelry, a single piece of flatware, two pieces of a porcelain figurine, a couple of furniture tacks, an eyeglass lens, pieces of two pocketknives, and a couple of snuff bottle fragments, among other less-distinctive items. These hint at some of the things Seaborn, Frances, and their children did while at home.

Although close to the big house, the yard around the kitchen and adjoining shed areas escaped the sweeping efforts. Excavations here recovered large quantities of all kinds of artifacts, including bones from butchered animals. The kitchen clearly was the center for a wide variety of daily activities, not only cooking and meal preparation but also mending or manufacture of clothing and manufacture of lead shot for hunting, to name just two important ones. It is likely that both enslaved African Americans, and perhaps freedmen after Emancipation, and the Hendricks engaged in these activities. Regardless of who did the work, it is certain that those activities were done on behalf of and controlled by the Hendricks, and thus the artifacts from this part of the site reflect their home lives more than those of the people they enslaved.

Artifacts and animal bones were moderately abundant at most of the cabins housing enslaved people, making it clear they too hosted a wide variety of daily activities. There were enough bones at four cabins to indicate the occupants butchered animals and cooked meals there, with the diet consisting of less beef than in the Hendrick household and more pork and wild game. Activities other than meal preparation and serving that were common in these cabins included replacing buttons on clothing, pipe smoking, playing mouth harps, and maintaining firearms. The enslaved certainly had lives apart from those of the slaveowners.

In taking a closer look at the question of how the artifacts reflect the lives of the planters and the enslaved, archeologists discovered some things they expected but others they did not. Among the unsurprising things was the fact that the kitchen had all or most of the coffee mill and cast iron stove parts, as that is where those kinds of implements would have been used. Also predictably abundant were pieces of broken alcohol and medicine bottles, since the kitchen would have been a logical place for these kinds of containers to have been stored and used. Sherds from other bottles also were more common in the kitchen than in the slave cabins, consistent with more-frequent use of consumables packaged in bottles and jars in the former.

Many of the kinds of artifacts that the archeologists found in equitable quantities at both the kitchen and the African American dwellings, that is, not especially abundant at one or the other, are the sorts of things that Hendricks family members and the people they enslaved could have used in their everyday lives. These items were related to horse tack such as bridle and harness parts, sewing items like straight pins and scissors, clothing hardware and fasteners like buttons and hooks, sherds from stoneware crocks and jars and yellow ware serving bowls, fragments of a variety of kinds of ceramic plates and other dishes, metal cans that stored foodstuffs, pieces of oil lamps, and fragments of personal items such as pocketknives, parasols or umbrellas, eyeglass lenses, and coins.

Among the things that surprised the archeologists was that so few (just three) musical instruments were found, all of which were mouth harps, and all of which were from the cabins of the enslaved. Missing were harmonica fragments like those found at the Ware plantation and pieces from accordions and fiddles, both of which were listed in an 1884 inventory of Seaborn Jones Hendrick Jr.’s pharmacy and dry goods store in Harmony Hill, part of the record of his bankruptcy.

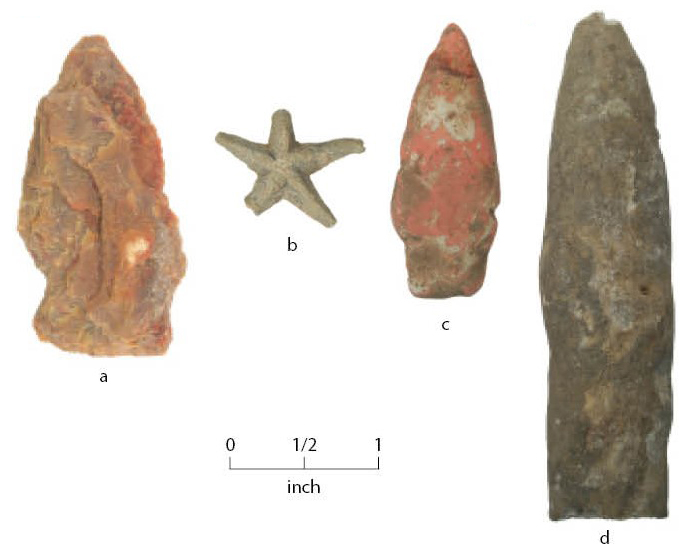

Also concentrated in the enslaveds' cabins were a handful of items considered to be collectibles, that is, a replica Native American dart point made from a brick, a stalactite, and a small lead star. These one-of-a-kind artifacts might not raise eyebrows, if it were not for the discovery of a rectangular metal can containing two bird bones and a cut nail at one of the cabins (which also yielded the replica dart point). These items hint at the use of spiritually charged objects by African Americans as a form of protection, to promote health and well-being, to invoke ill will or harm, and to influence the future. Such practices, albeit with different kinds of artifacts, have been

documented at a variety of other slave

sites across the southern U.S.

A wide variety of other kinds of artifacts were more frequent in the cabins than the archeologists expected. These included firearms-related artifacts, mostly lead shot but also gunflints and gunflint holders, musket and percussion caps, and a bullet; writing slate, slate pencils, and ink bottle glass; architectural hardware such as hinges, door and window latches, and doorknob fragments; beads, a brooch, and a jewel setting; ceramic tableware sherds of all kinds, with decorated wares especially frequent; sherds from pressed glass vessels, probably mostly tumblers; flatware consisting of forks, spoons, and knives; cast iron and thin stamped iron cooking vessels; a fireplace andiron; furnishings-related hardware such as furniture tacks, drawer or cabinet pulls, a trunk handle, and a cabinet or trunk latch; padlock fragments; children’s toys, including ceramic doll parts and marbles; personal grooming items, including comb fragments and a decorated ceramic shaving cream jar; and tobacco pipes and glass snuff bottle fragments. These indicate that the people enslaved by the Hendricks had access to and used a varied material culture in their everyday lives. They hunted some of their own food, likely provided some amount of educational instruction to their children, furnished their cabins with more than the bare necessities, participated in leisure activities, and retained personal possessions.

Neither the archeological record nor archival records indicate how this came to be, but it seems likely that the enslaved did most of these things, with the possible exception of retention of spiritual practices, with the Hendricks’ knowledge or maybe even encouragement. Certainly, allowing the enslaved to hunt for some of their own food could have worked to the Hendricks’ advantage, since it lessened their burden to provide food. Allowing them to keep firearms implies a level of trust that may run counter to traditional expectations about enslaver–enslaved power relations, but this practice has been documented elsewhere in the South.

Probably some of the material culture listed above can be explained simply by the enslaved reusing things the Hendricks discarded or lost. It is easy to imagine that the orphaned, and probably broken, fireplace andiron ended up in the slave cabin by that route. This could have been the case for some of the architectural and furnishings hardware as well, and maybe the children’s toys.

Other kinds of artifacts may be things that the Hendricks provided because they considered them essential household supplies, such as the flatware and cooking vessels, or that they handed down to the enslaved after they no longer wanted them. The ceramic tablewares may provide evidence of the Hendricks giving old dishes to the enslaved after they bought new ones. Decorated ceramics of all sorts were more common in the slave cabins than in the kitchen and the big house, where white granite ware (both plain and molded) predominated. White granite was introduced in American markets during the 1840s and became the dominant style by the 1860s, replacing decorated wares that had been popular in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The Hendricks probably used these decorated dishes early in the plantation’s history, with individual vessels ending up in the cabins of the enslaved as hand-me-downs from the Hendrick household, which was using mostly white granite by the Civil War and after.

Some of the artifacts are things that enslaved African Americans either created themselves, such as the replica dart point fashioned after a genuine stone point they found on the surface at the nearby spring, or that they acquired through purchase or barter, for example, the numerous clay smoking pipes and the personal and grooming items. The few coins found attest to the fact that they had the means to buy things, and the wild game the slaves hunted and the fish they caught would have given them something to barter with. In both instances, the Hendricks likely controlled whether they had the opportunity to do this—slaveowners allowing the people they enslaved to participate in economic activities was not unheard of.

Ultimately, the archeologists concluded that they could tie some, but not all, of the artifact distributions into neat packages conforming to expectations about how the lives of the Hendricks and the people they enslaved differed and were similar. The behaviors of the people who lived there, enslaved and slaveowners alike, and the ways in which those behaviors created the archeological record were just too complex. This does not even consider nonhuman factors confusing the picture that archeologists always have to contend with, such as disturbance from erosion and land clearing and poor preservation of organic materials like cloth and food remains. The artifacts hinted that the 20 enslaved people who lived at the Hendrick plantation in 1860 did not live lives of absolute deprivation. Yet, the material remains could not speak directly to how being subjected to the racist institution of slavery impacted the daily well-being of enslaved people on the Hendrick plantation.