Archeological excavation and archival review proved a powerful combination in the study of the Hendrick and Ware plantations. Archival records, such as old newspapers and those in government archives, contain information about people and events with a level of detail that archeology usually cannot match. However, archeology provides tangible evidence of past behavior, supplementing and sometimes challenging the written record and our preconceived notions of the past. In the case of these northeast Rusk County plantations, archeology and archival review complement one another, offering a fuller picture of plantation life in the mid to late 1800s.

This section explains how these dual avenues of research were used to explore the Ware and Hendrick plantations. The project historian metaphorically unearthed information about plantation economies and histories of planter families from archival records, and archeologists literally excavated the dwellings of enslaved African Americans, the planter families' houses, and other plantation infrastructure.

Project History

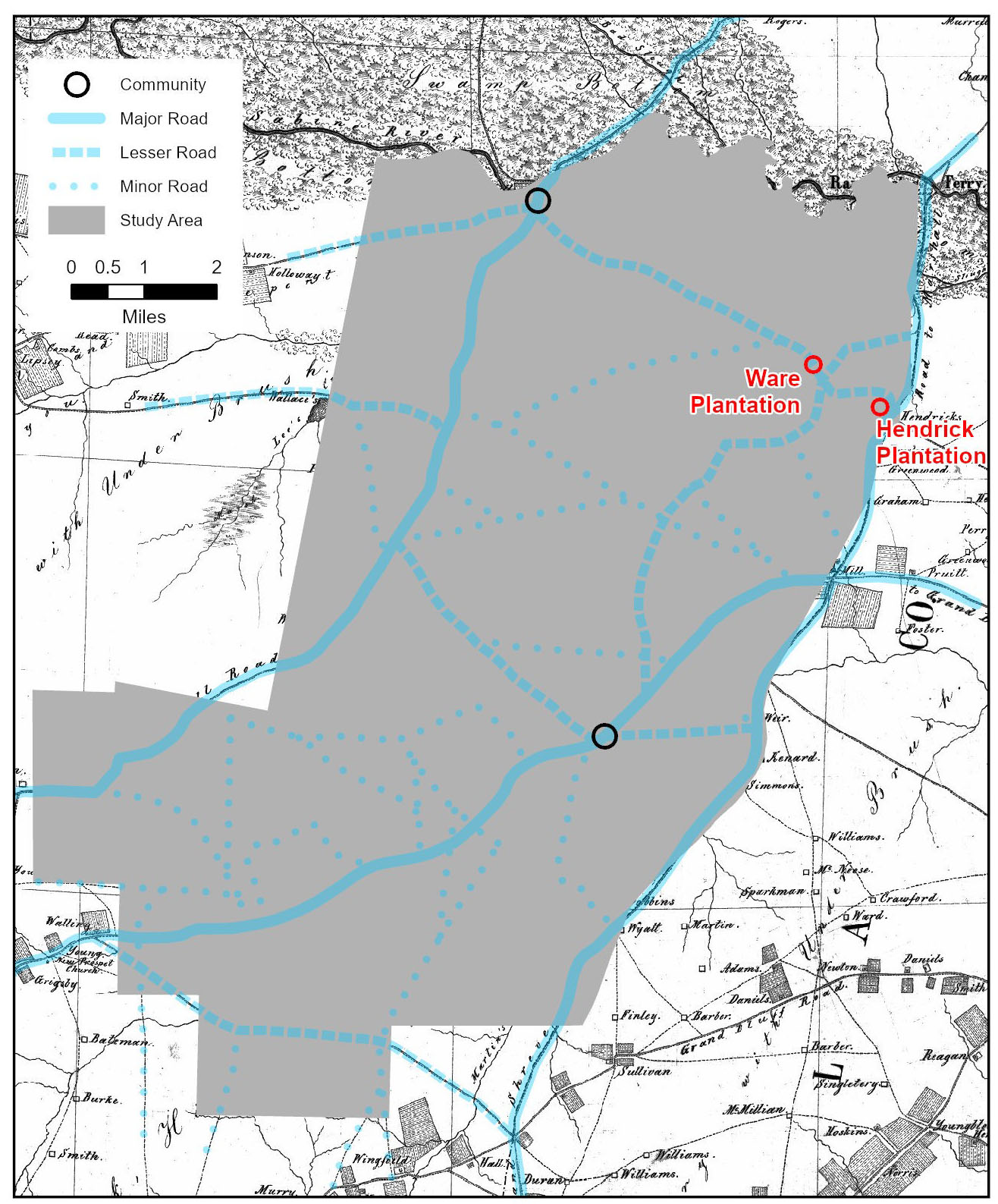

Archeologists from Prewitt and Associates, Inc., identified the Hendrick and Ware plantations during survey for a proposed lignite mine. Mine sponsor North American Coal Corporation–Sabine Mine hired the archeologists to survey the area in compliance with laws such as the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. The archeologists’ discovery of scattered artifacts, sandstone foundation stones, and brick chimney bases in the proposed mine area triggered the Hendrick and Ware plantation research project, which unfolded between 2008 and 2021.

In 2008, archeologists conducted an initial survey of the proposed mine location, finding and recording surface evidence of the Hendrick and Ware sites and digging shovel tests to search for buried deposits. In 2013, archeologists returned to the plantation sites to determine whether they might be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. To be eligible, the sites must have the potential to convey important information about plantation life in northeast Texas. To help determine this, Archaeo-Geophysical Associates, LLC, performed exploratory remote sensing with a magnetic gradiometer, and archeologists from Prewitt and Associates hand-dug test units and trenches. Though they found that twentieth-century plowing and modern pipeline construction had disturbed parts of the sites, both plantations had substantial areas with intact archeological deposits.

Also in 2013, archeologists exhumed the remains of three individuals from the Ware Cemetery, including Levi Hill Ware and his infant son, and relocated them to a perpetual care cemetery in Henderson, Texas.

The project design that guided the extensive final excavations outlined two research topics: plantation layout, and social environment and economy. The first topic sought to discover spatial distributions among plantation features—such as dwellings, agricultural fields, and cemeteries—the function of each, and construction methods. Nothing of the plantations’ nineteenth-century built environment remained standing. Only materials like foundation features, window glass, and metal fasteners, such as nails, could point to construction methods. Because the period of interest spanned four decades (1850s–1880s), researchers were interested in how plantation infrastructure developed and changed, the differences between laborer and planter dwellings, and other intriguing topics.

Researchers divided a second broad research topic—the local social environment and economy—into three themes: power and inequality, social and cultural practices, and plantation economies. Research questions explored the local economy, social and economic differences between planter families and the enslaved communities, the daily life and diets of plantaion occupants, plus the effects of the Civil War upon these.

Finally, during two lengthy fieldwork episodes between 2015 and 2018, archeologists excavated areas of the Hendrick and Ware plantations deemed best able to address these research topics.

Hendrick Plantation Archeology

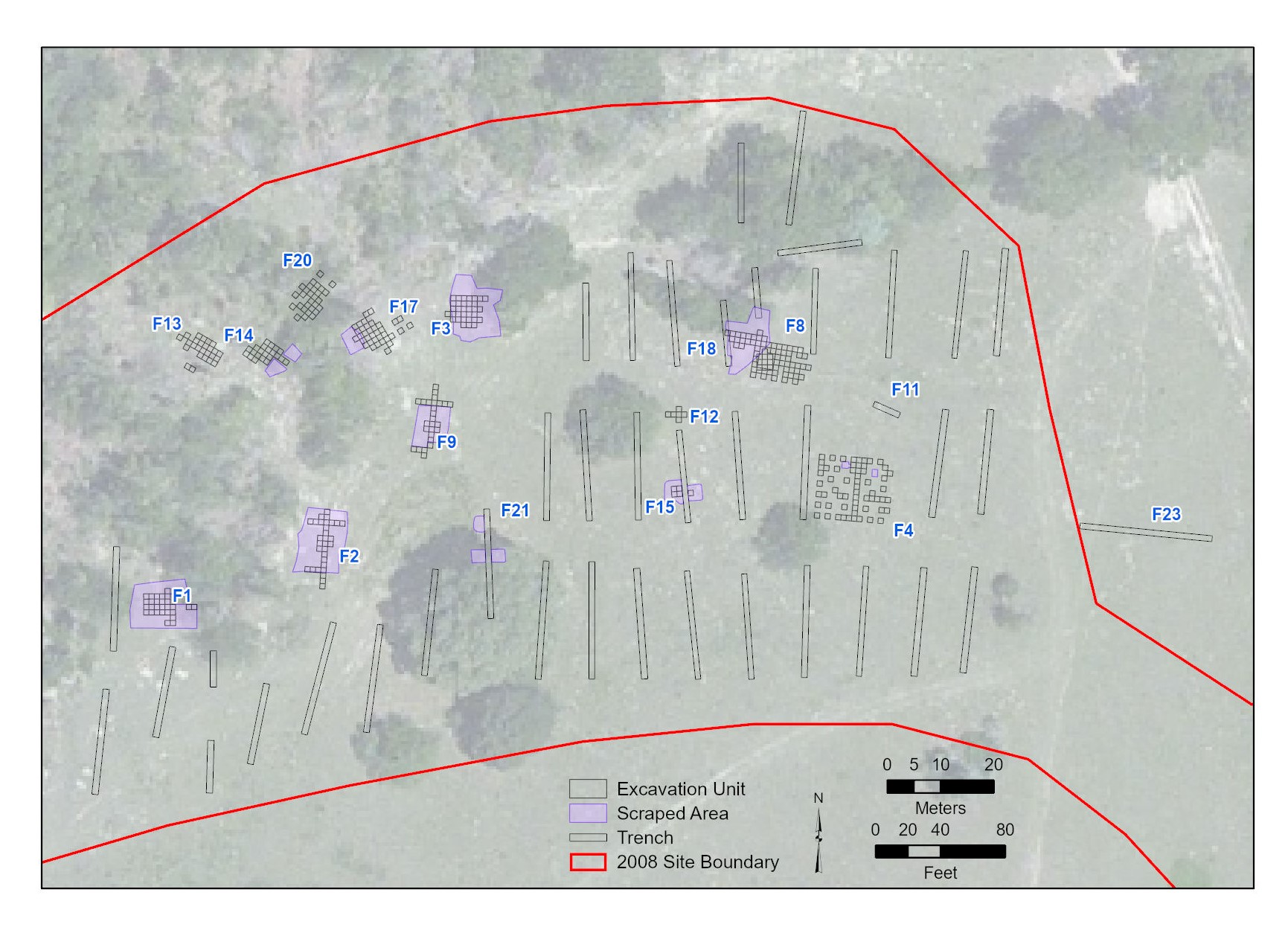

Because the Hendrick plantation had better-preserved archeology with potential to address a range of research topics that the Ware plantation could not, excavations were much more extensive here. Archeologists used several methods to explore below the ground surface, including scraping, mechanical trenching, and hand-excavation. These tasks occurred in different areas of the site concurrently, rather than successively.

The final, extensive excavations of the Hendrick plantation occurred between September 2017 and March 2018. Mechanical trenching conducted across the eastern and southwestern parts of the site searched for features around and between those documented in 2013. The archeologists’ objectives in the final fieldwork session were to verify that all buildings and structures had been discovered.

In a thickly vegetated area where the remains of two dwellings of enslaved African Americans had been identified during the preliminary test excavations, archeologists cleared understory vegetation and scraped the ground surface to search for additional features. Chimney bases representing the locations of three dwellings were found during this effort.

Fireplace remnants, present in most of the Hendrick plantation dwellings, were distinctive features that archeologists used to determine the orientation of the plantation's many buildings. By excavating fireplaces first, archeologists could place additional excavation blocks to fully uncover these buildings. For example, at the Hendricks’ detached kitchen the fireplace opened to the east, indicating that the adjoining building extended in this direction.

Excavation of the enslaveds' dwellings also employed this approach. After archeologists determined the direction of the fireplace openings, they established a block of units that aligned with that orientation. For some dwellings this method was easy, but in other cases the fireplace opening could not be determined. In these challenging cases, archeologists positioned excavation units based on patterns seen at nearby features. They also employed mechanical scraping, primarily around chimney features following hand excavation, investigating more deeply buried architectural components. Archeologists unearthed some cabin piers as a result, but found that most of these dwellings did not have large piers like those that supported the Hendricks’ house.

Other features excavated at the Hendrick plantation included trash pits in the big house yard area and fireplace and foundation remnants of three small houses near the dwellings of the enslaved, but probably occupied by Euro-Americans. An area of modified, rock-lined creek bank at the plantation’s main water source was also excavated, as well as a portion of the shallow swale that marks Trammel’s Trace—the important interstate route that crossed the Hendrick property. Nearly 33,000 artifacts were recovered in the Hendrick plantation excavations, as well as faunal and botanical remains such as animal bones and seeds.

Ware Plantation Archeology

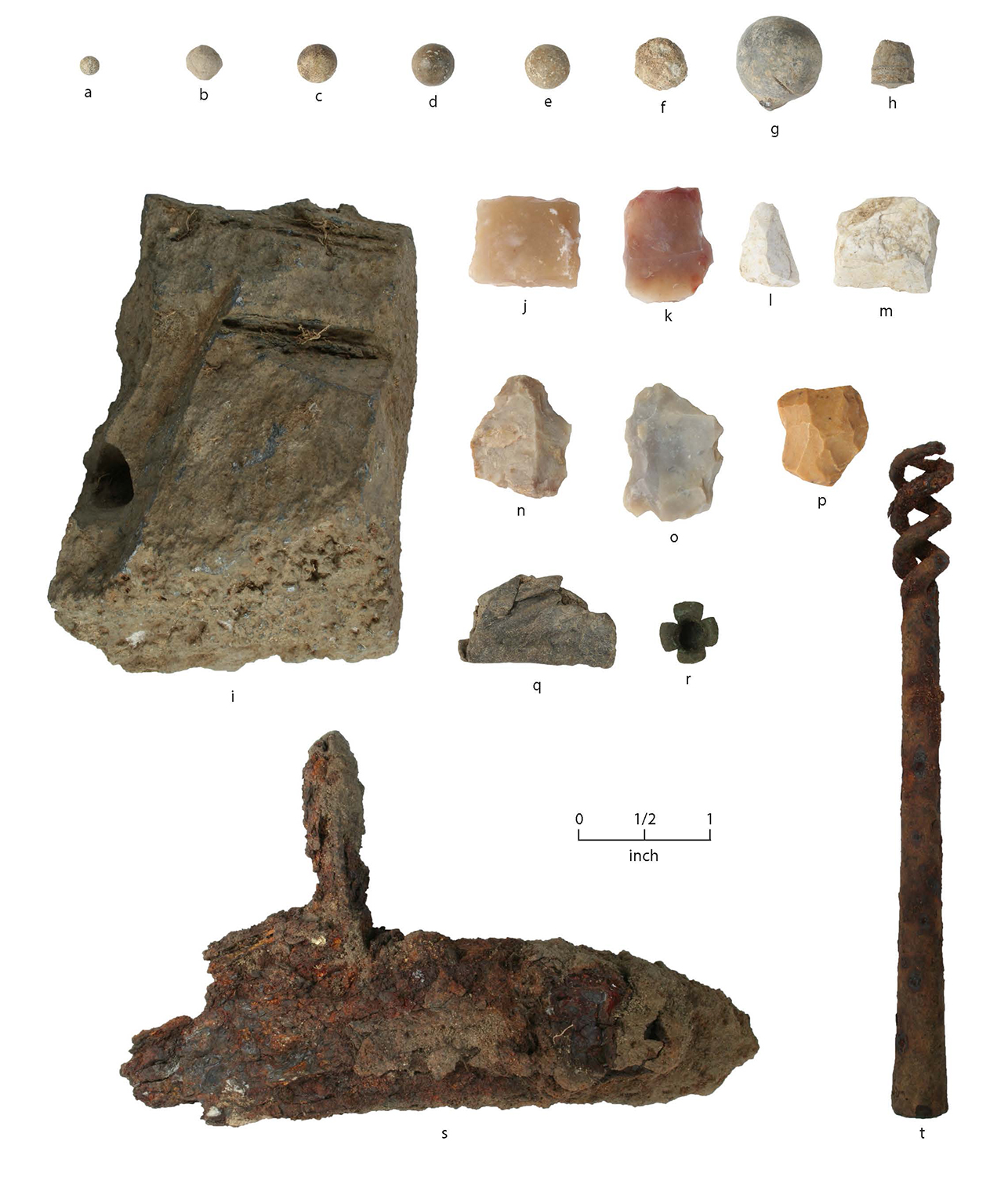

Final excavations at the Ware plantation took place between October 2015 and February 2016. During this field season, archeologists began their work using metal detectors to locate concentrations of metal artifacts, especially nails, that could mark locations where buildings and structures once stood. The results of metal detecting guided subsequent shovel testing, trenching, and scraping. Lastly, archeologists undertook block excavation in areas deemed most likely to address their research questions.

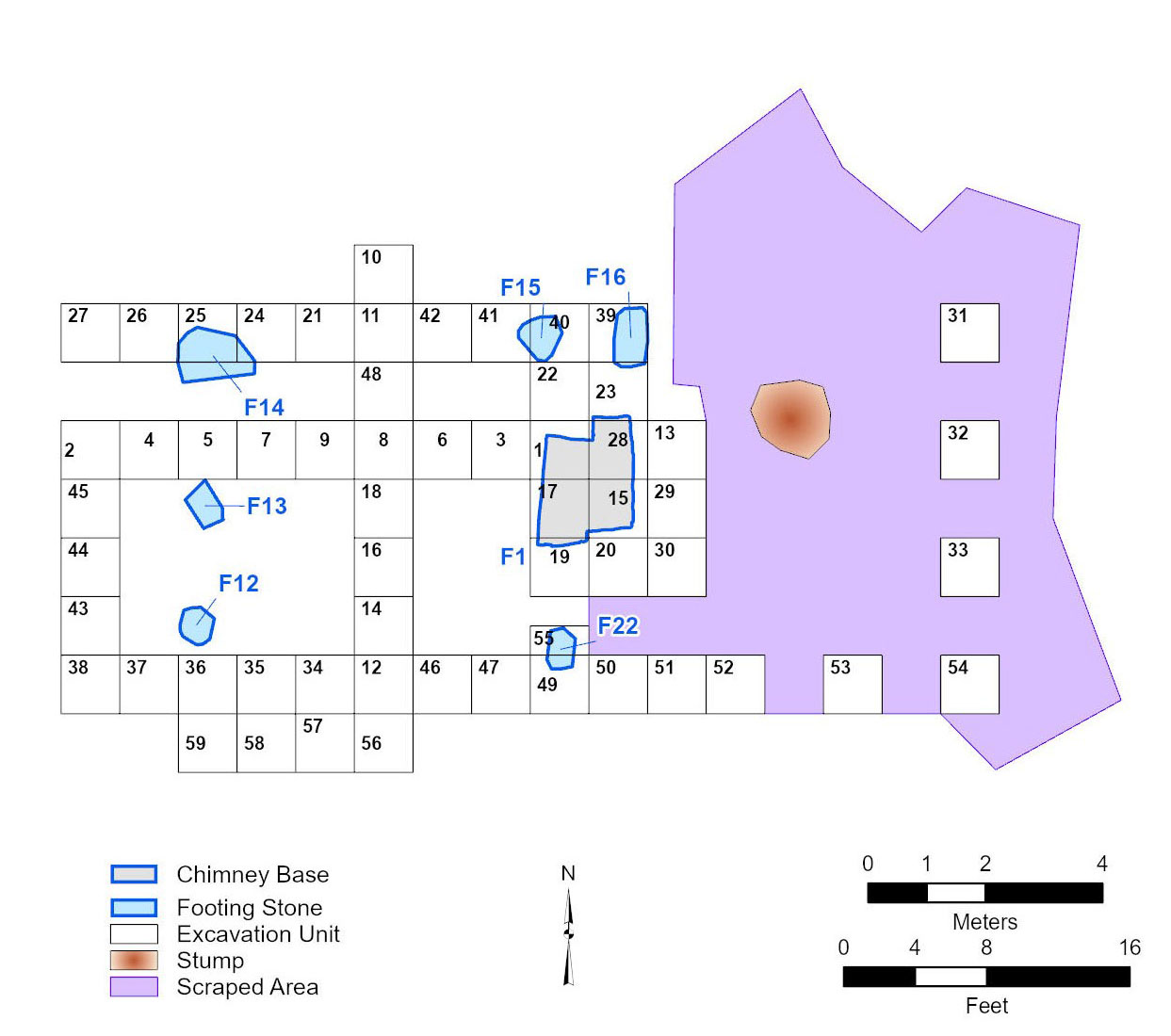

The best-preserved archeological features at the Ware plantation were the brick chimney base and associated sandstone footings that indicated the location of a small cabin. Probably built in 1845 or 1846, the dwelling pre-dates the Wares’ arrival. It was likely the home of the previous property owners, Ann Mariah Foulks Ellis Camp and her two successive husbands, Benjamin Franklin Ellis and Joseph Camp. After purchasing the property, the Ware family probably lived in this modest dwelling while their permanent house was constructed on the hilltop to the north. After the Wares moved into their new house, a plantation overseer may have lived in this small cabin.

The final excavations were at the small Ellis/Camp/Ware cabin. Archeologists set an 8x12-meter grid across this area and reopened the 2013 test units. They then dug a series of 1x1-meter units along the east-west base line and across the north-south base line. After completely exposing the chimney base, archeologists placed additional units to examine the footing stones evident on the surface, search for subsurface stones, and further investigate the southern edge of the former dwelling where the family discarded much household refuse. In addition, archeologists excavated 1x1-meter units east of the grid in a search for an anticipated eastern room. No additional footings were found however, nor were any exposed when a backhoe scraped the area.

Years of plowing disturbed the remains of other buildings once located near this first dwelling, and excavations in these areas identified only scattered footing stones and artifacts. The northern part of the site, which contained the main plantation core, including the Ware's larger, second house, was also heavily disturbed. Excavations there found scatters of brick rubble, sandstone footings, artifacts, and a hand-dug water well, but few intact features.

Archeologists collected all artifacts, except bricks, for later identification and analysis in the laboratory. In total, the Ware plantation excavations yielded 6,435 artifacts. Archeologists grouped them based on their functions: architectural, kitchen and household, activities, clothing and adornment, and personal items. Items not easily placed into these categories, mostly rusted pieces of iron, were considered unidentifiable. Archeologists also collected and analyzed samples of faunal remains, like animal bones and mussel shells, and botanical remains, notably including numerous peach pits.

Ware Cemetery Excavation

In 2013 archeologists disinterred three burials—that of Levi Hill Ware, his unnamed infant son, and the unmarked grave of Walter O. Robinson—from the Ware Cemetery, a short distance north of the plantation core. The remains were later reburied in a perpetual-care cemetery in Henderson, Texas. Work began with hand excavations adjacent to the headstones and careful backhoe excavation to look for more graves. Archeologists discovered a more-complicated situation than they had anticipated; the headstones extended well below the modern surface, and scraping identified brick features that turned out to be false crypts atop the graves of Ware and his son.

Before excavating the burials of Ware and his son, archeologists conducted mechanical scraping to look for unmarked graves around the known burial plots. They then removed vegetation from the cemetery, including a large yaupon tree growing on top of Ware’s grave. Finally, the archeological team removed headstones and footstones, dismantled the brick false crypts, guided machine excavation beneath the crypts until evidence of the Ware interments was found, and hand excavated the interments.

The unmarked interment of Walter O. Robinson was identified during the machine excavation in search of the Wares’ interments. Robinson was an in-law of the Ware-Flanagan family. Born in April 1851, he died in the nearby community of Flanagan on January 2, 1909.

Archival Research

Archival research for the Hendrick and Ware plantation study entailed compiling annual tax data for the two families and their neighbors and analyzing and synthesizing tax, census, and property ownership records to address questions about land use, settlement, and economics in the decades before and after the Civil War. This data gathering and analysis effort was enormous, and resulted in a detailed understanding of northeast Rusk County’s evolving agricultural economy. The historian also traced the Ware and Hendrick families to their home states in the southern United States—South Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia—and stops on their journey to Texas.

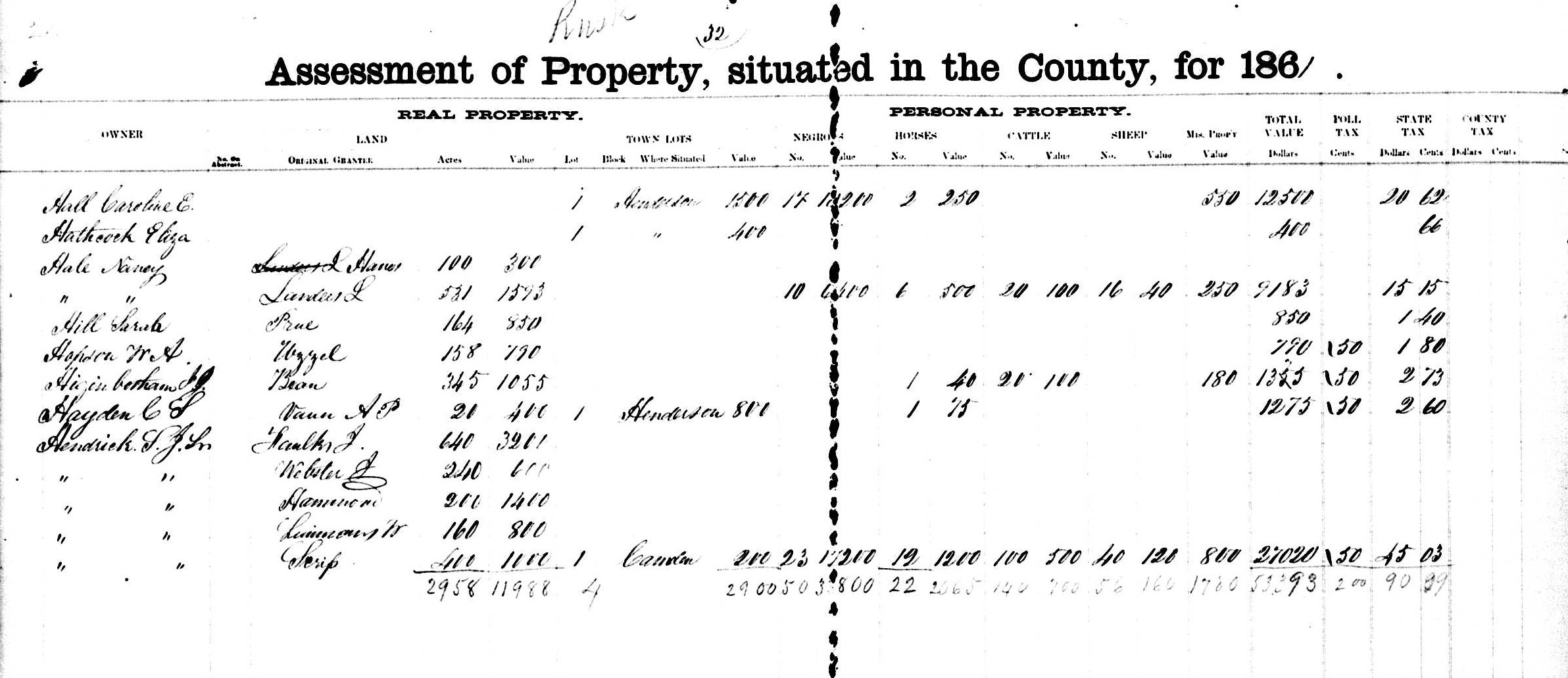

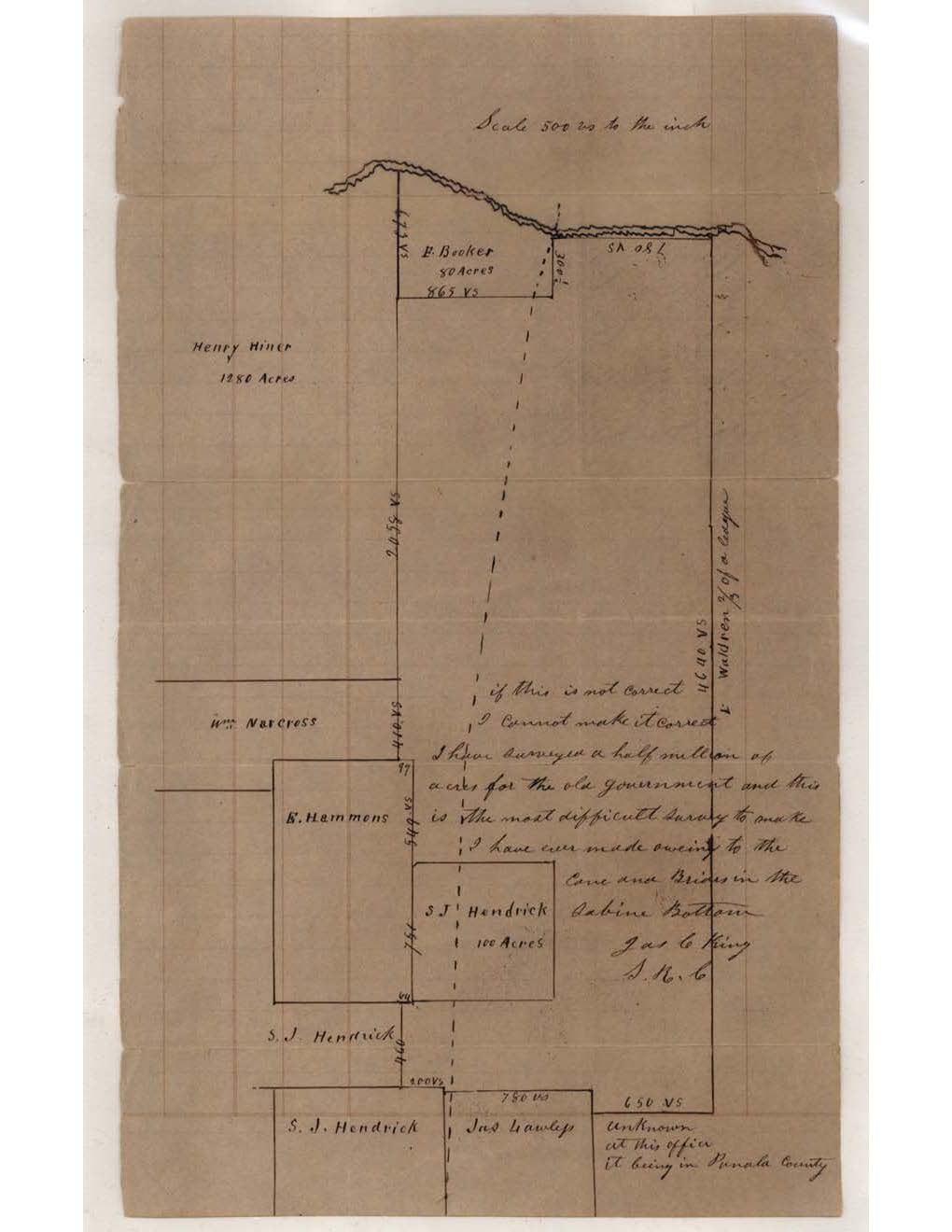

Primary source research was initially guided by surnames and the time period of interest (1840s–1880s). The historian identified the 73 earliest local landowners using land grant survey documents and identified 34 late-antebellum occupants using an 1863 map. Annual ad valorem taxation began in Rusk County in 1842, and tax documents listing land owners names and the values of their properties provided detailed information about each. The historian amassed tax data for each landowner known to have lived in the area between 1842 and 1864. Some information about landless men was also collected. The quantity of data was overwhelming—5,000 rows of entries! As a result, the historian focused on the 78 long-term farmers and planters (54 of whom were slaveholders) whose tenure overlapped those of the Hendrick and Ware families.

Another important source of information was the federal decennial manuscript censuses for 1850 and 1860. Censuses documented the enslaved and free populations and agricultural production. Population censuses denote demographics of free citizens: name, age, gender, occupation, real and personal wealth, and place of birth. The slave censuses, on the other hand, list the slaveowner’s name, not the name of the enslaved, and age, gender, and color (that is, race; black or mulatto) of the enslaved. The 1860 slave census also records the number of slave dwellings by owner. The agricultural censuses account, by farmer, for the amount of improved and unimproved acreage, farm value, implements and machinery value, number of horses, asses or mules, oxen, dairy and beef bovines, swine, ovines, and bushels of corn, oats, wheat, and rye. The 1860 agricultural census, in addition, lists the number of ginned cotton bales, pounds of wool, butter, and honey, bushels of peas or beans, potatoes, and sweet potatoes, value of homemade products for home use or sale, and value of animals slaughtered.

Tax and census records convey exceptional information but each has certain biases, deficiencies, and advantages. In the case of either type of record, citizens were likely to honestly report whether they did or did not enslave people. However, some slaveowners underreported the number and value of the enslaved to lower their tax payment. Enslaved infant and the elderly, for example, were considered less valuable since their labor contributions were minimal, and they were often excluded or undervalued. A comprehensive study of slavery in Texas that relies heavily on tax records suggests that assessors consistently undercounted the enslaved by 10 to 20 percent. Conversely, slaveowners were likely to precisely report the number and specifics about slaves they held to census takers, since bondsmen counted toward the Three-Fifths Clause, which advanced slaveowner interests. The Three-Fifths Clause, or compromise, counted three-fifths of the enslaved population towards each state’s allotment of seats in the House of Representatives and presidential electoral votes, and affected states’ taxation. Thus, the slave censuses provide detailed, and probably more accurate if less frequent, snapshots compared with annual tax records that are useful because they provide an annual view.

The historian relied on other sources to track land ownership and other historical events. Texas General Land Office files note the date the government released each land grant from the public domain and patented the property to a private owner. County deed and probate records document the subsequent conveyance of property. Useful secondary sources about local people, places, and events included the University of North Texas’s Portal to Texas History, the Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas Online, and other public or subscription websites, including Ancestry, Family Search, and Find A Grave. Newspaper and journal articles and locally sponsored web sites provided additional insights into community history.