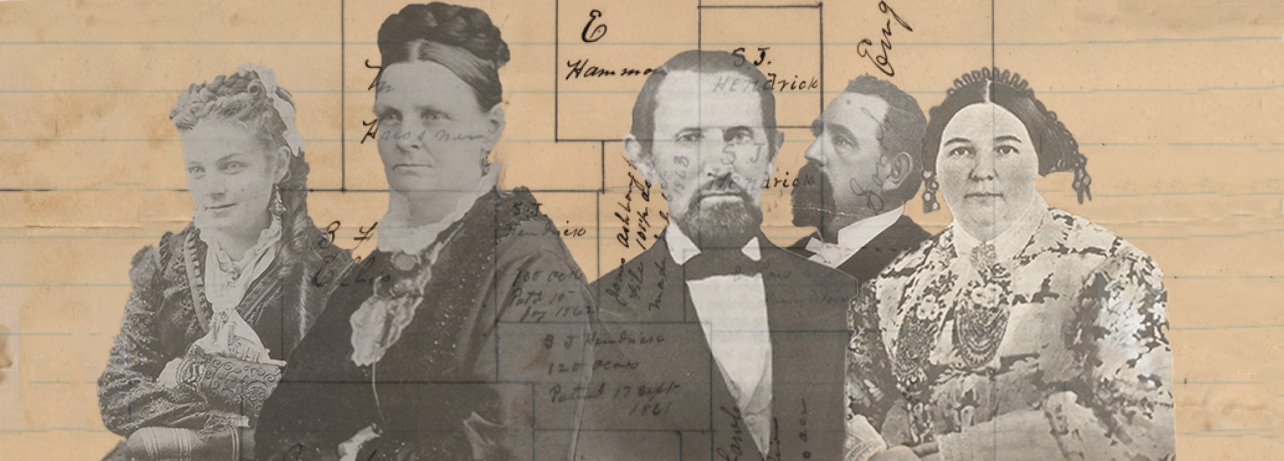

This section details the personal histories of the Euro-American planter families who owned and operated neighboring northeast Texas plantations: that of Georgia-born Seaborn Jones Hendrick Sr., his wife Frances “Fannie” Smith Hendrick, and their nine children, and that of South Carolina–born Levi Hill Ware, his wife North Carolinian Elizabeth “Betty” Hinton Vinson Ware, and their two surviving children. Information about these families comes from archival records, including county taxes, federal censuses, marriage licenses, church files, genealogical information, and newspapers.

Hendrick Family

Seaborn Jones Hendrick Sr. and his family journeyed to Texas after his mother had relocated there from Georgia. Seaborn was one of two sons born to Martha Ann Baker and second generation Irish-American John Hurt Hendrick Sr., who was killed in Georgia by Native Americans in 1816. After his death, Martha remarried, was widowed again, and relocated to Texas where she married her third husband, Allen Vince. Vince was an “itinerant Catholic” of importance for involvement with the 1836 Battle of San Jacinto, the critical confrontation and defeat of the Mexican Army that ended the Texas Revolution. General Sam Houston reportedly dined with the Vince family the evening before the fight.

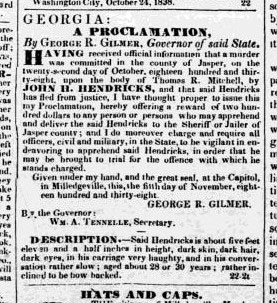

Seaborn’s brother was John Hurt Hendrick Jr., who briefly lived on his younger sibling’s plantation. Little is known about John other than his questionable reputation, at least in Georgia, where a warrant and reward called for his arrest for murder; he reportedly attacked a man, a relative of his mother’s, with a glass tumbler and a large stick. The warrant uncharitably describes John as “in his carriage very haughty, in his conversation very slow… [and] rather inclined to be bow backed.” He enlisted with the Confederate Army and died in 1862 at the Battle of Richmond.

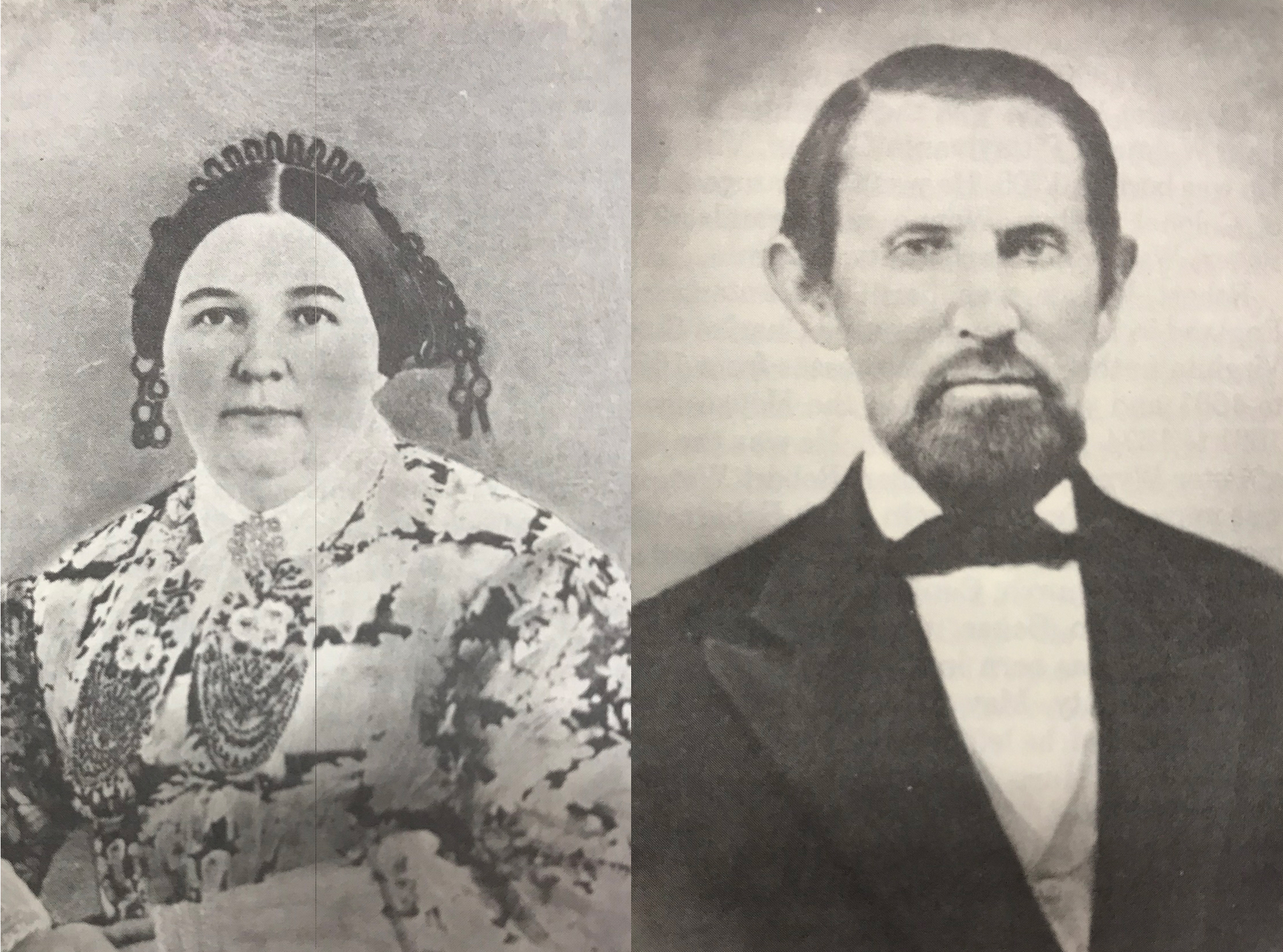

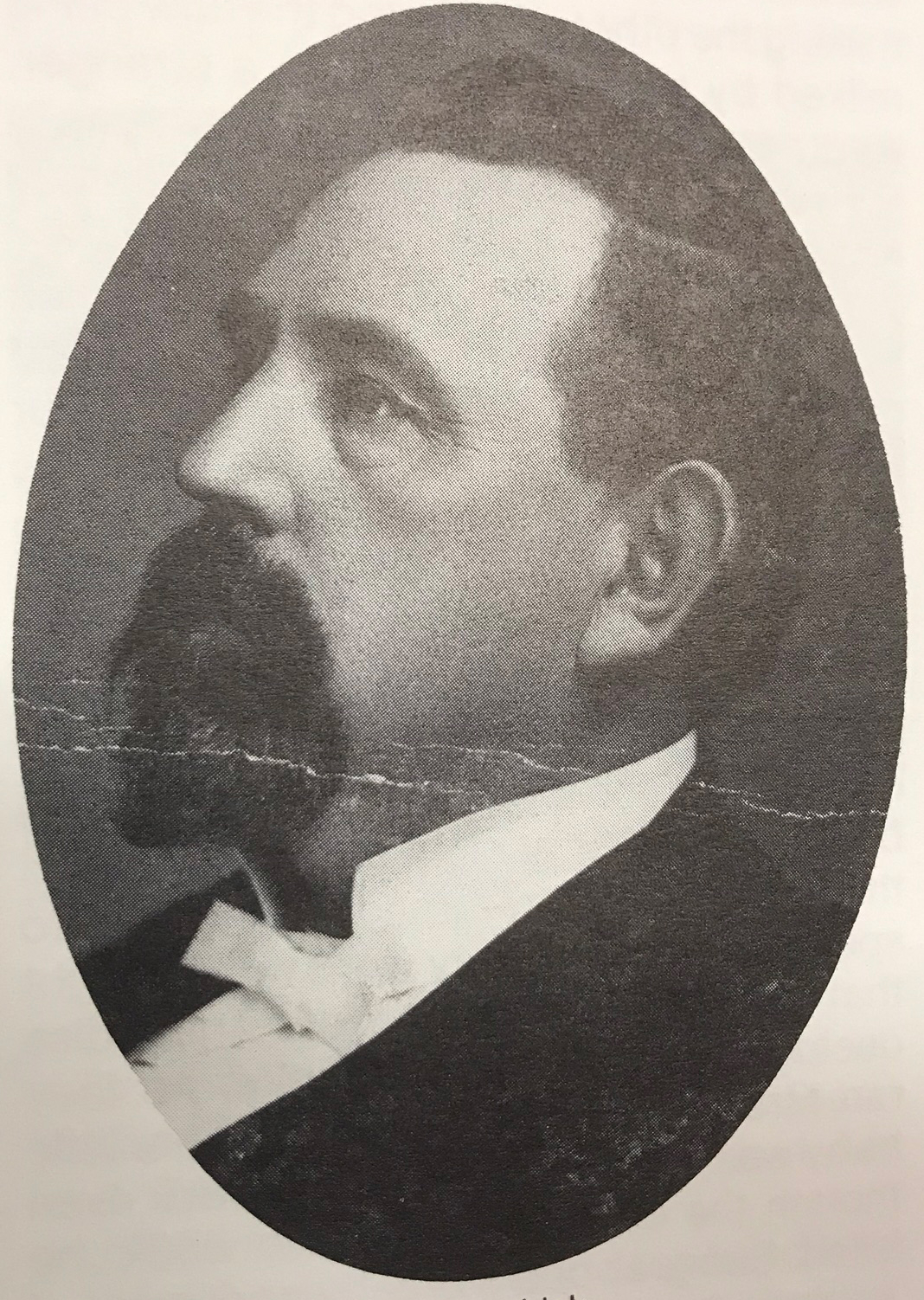

Seaborn was apparently quite different than his brother. He had political ambitions in Georgia, where he ran for the Jasper County sheriff’s office, and was a doctor, farmer, and family man. Seaborn and Frances Evalina “Fannie” Smith married in Georgia. He was in his early 20s when they married, and she was 19.

While they lived in Georgia, Seaborn and Frances had two children, John Stephen, and a daughter who died in infancy, Martha Ann Vince. The Hendrick household also included at least two enslaved people, a man and a woman each between 10 and 20 years old. In 1841, the family migrated to Alabama. Despite this relocation, Seaborn maintained ties to Jasper County, Georgia, where he sold an enslaved female named Creecy to a local estate several years later. In Alabama, the couple had three more children—Allen Vince, Emma Caroline, and Wesley Hall.

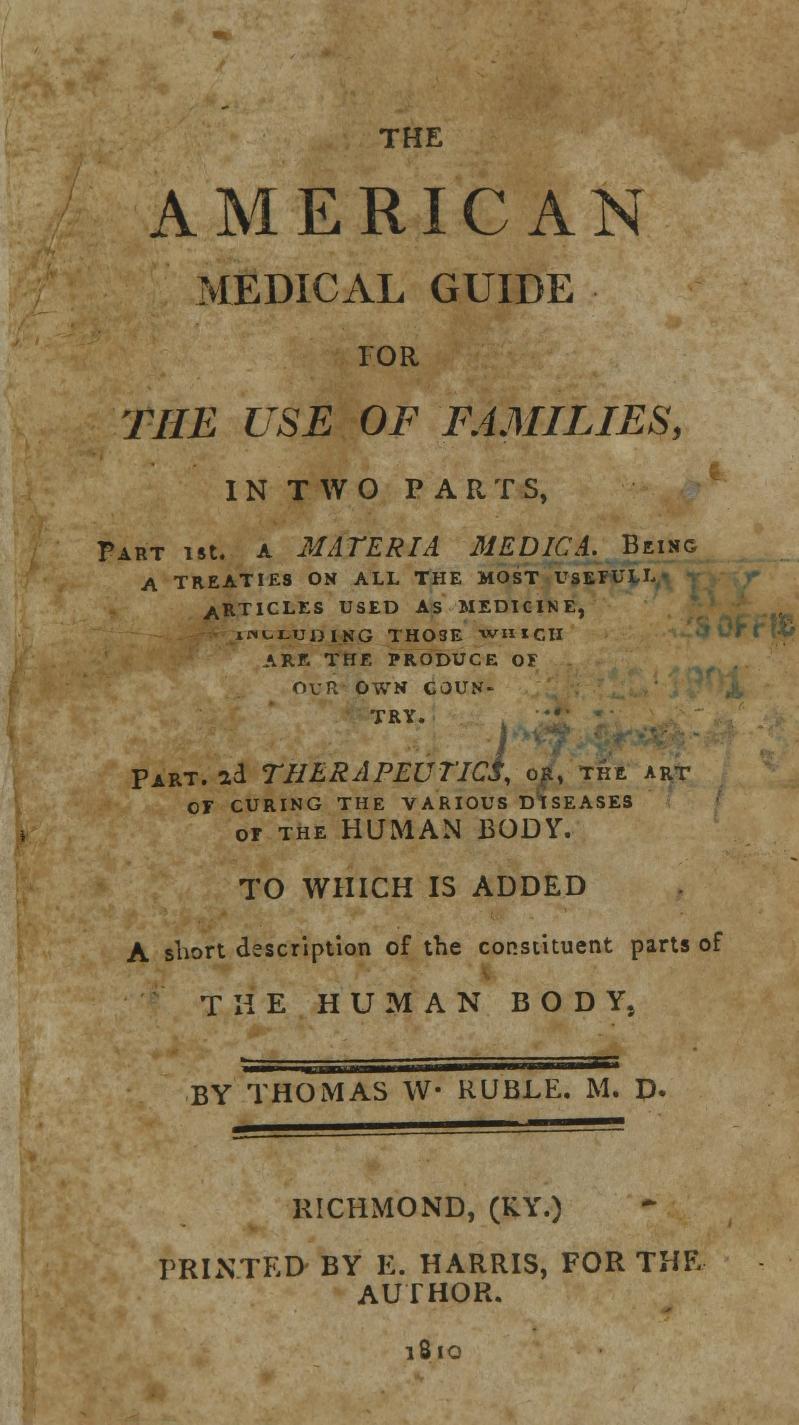

Seaborn may have undertaken medical training at the Alabama Medical Institute, approximately 40 miles from his Alabama property, or he may have attended medical school at the Southern Botanico-Medical College—the first sectarian medical college in the South. Seaborn probably at least had a mentor or was apprenticed to a practicing doctor.

Seaborn's involvement in Texas began in February 1844, when his mother and stepfather conveyed 500 acres in Fort Bend County to him for $1,250. He and his family may have been in Rusk County by 1847, and certainly by March 1848. That year, the Hendricks’ had a fifth child, Seaborn Jones “Sebe” Jr. By June 1850, the family was indelibly settled in northeast Rusk County. That month, Seaborn’s by-then thrice-widowed mother married again, this time to Virginia-born Reverend Obediah Dodson, at the family’s Rusk County plantation. Dodson was a teacher at a school on or near the Hendrick plantation, and a Baptist minister.

By the start of 1852, the corpus of Seaborn’s land holdings were solidified. The 640-acre Foulks and 160-acre Simon Surveys formed the plantation core, and the 640-acre Webster and 200-acre Hammers Surveys were short distances away to the southwest and north. He had acquired the Webster Survey first, in September 1850, and in 1851 he acquired the other three big pieces of land. A sixth child was born in 1851, Albert Lassiter Smith “Las.” Before the decade ended, the Hendricks would add three more children to their household Anna Maria, Frances Evelyn “Fannie,” and Julius Augustus Kendrick “Jule.”

Again, Seaborn’s mother Martha was widowed when his stepfather, Obediah Dodson, died in 1854. Subsequently, Martha resided in a small house on the plantation. In her later years she retained enough stamina to ride a mule to Coosa County, Alabama, for a visit before returning to the Hendricks’ Rusk County plantation. On July 12, 1869, 70-year-old Martha Ann Baker Hendrick Malone Vince Dodson died and was buried in the nearby Greenwood Cemetery, where her fourth husband was also laid to rest.

In July 1871, matriarch Frances died at the age of 53. After her death, Seaborn moved to Harmony Hill for a time. In January 1875, he and the widowed Sarah/Sallie Johnson Alexander Harris married. They likely resided on his Rusk County plantation for the duration of their marriage.

After Seaborn’s death on June 24, 1882, his heirs retained the family lands for decades. No relations occupied the land full time, if at all. Seaborn’s second wife and widow may have resided on the homestead until 1892, and possibly until her death in 1896, although archeological evidence for occupation that late is very sparse.

Hendrick Children

Of the 10 children born to Seaborn and Frances, nine lived to adulthood. The eldest, John, was working as a merchant by age 22. In 1861, he and brother Allen, the second-eldest son, enlisted in the Confederate Third Cavalry Regiment. For much of his service, John was a commissary clerk for one or another of the brigade’s majors, but he had a stint as acting adjutant for a battalion of sharp shooters. In 1864, the Hendrick brothers’ regiment flanked Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston’s army, skirmishing nearly daily alongside other troops in the Atlanta Campaign in Georgia. Both sides lost more than 30,000 soldiers each. Though the losses were great on both sides, the smaller Confederate army was at a disadvantage after these skirmishes. The reduced Confederate regiment repositioned to charge a railroad that supplied Union forces. John and another Rusk County private had been on support detail until this attack, when orders for their safer assignments were cut to boost fighting strength. Both were killed their first day on the field. John was 26 years old when he died. His brother, Allen, lived through his army assignment and returned to Rusk County. He became a retail merchant in Henderson and later farmed near the Hendrick plantation with his wife and two children.

Most of the Hendrick children remained in Rusk County as adults. The eldest daughter, Emma, married William Tatum, son of the founders of nearby Tatum, Texas, sometime after 1860. Emma’s husband returned home wounded after fighting in the Civil War and was dead by 1870. Twenty-six-year-old Emma and her young daughter Lola resided with her parents and youngest siblings on the plantation after she was widowed. In 1874, Emma married local physician Angus Gilchrist Shaw. The couple likely met through one of her brothers, who boarded with Angus in Henderson. The Shaws lived in Harmony Hill and owned several properties. Emma’s younger brother Albert, who remained single during his lifetime, lived with them for a while when he worked as an overseer at a convict farm. By 1880, several other Hendrick relations lived in the Shaw household, including Emma’s sister Anna and a nephew. Anna, the second-youngest Hendrick daughter, eventually married a retail dry goods merchant in Henderson, where the couple resided with their four children. The youngest Hendrick, Julius, farmed with his brother Allen for a time, and later lived in Henderson and operated a farm he owned. Seaborn Jr., a middle son, also worked in Harmony Hill, where he owned a drug and grocery store. Seaborn Jr. was known to be a colorful character, dabbling in a range of failed and successful business interests, from farm laborer to druggist to lawyer and judge. He married Ellen Amelia Hall, and they had two daughters, one of whom died in infancy.

Not all the Hendrick progeny stayed close to home. The Hendricks’ third-oldest son, Wesley, boarded with a family in Camden, Arkansas, where he was a contractor and builder. Their youngest daughter, Frances, lived in adjacent Gregg County with her grocer husband William Thomas Thompson. By the 1880s Frances and William had several boarders, both white and black, most of whom were railroad workers.

Ware Family

Levi Hill Ware, native to Spartanburg, South Carolina, and Elizabeth Hinton “Betty” Vinson obtained a marriage license on January 26, 1846, in Madison County, Tennessee. Little is known about their lives together until 1851, when Levi’s Rusk County property was first appraised for taxes. Records for Elizabeth’s father, North Carolinian John/Jack Addison Vinson Sr., link the Vinson family to Tennessee and Texas. He was on the move in 1850, when he had plantation homes in both states. Signaling his imminent departure, two Baptist churches released Vinson and two of his daughters from their congregations in 1850. Another church dismissed 12 people Vinson Sr. enslaved, who presumably travelled with him to Texas. The Wares’ move to Texas may have concurred with that of Elizabeth's parents, and the Wares, too, likely brought enslaved people with them.

After arriving in Texas, Levi amassed real estate for the family plantation in northeast Rusk County. His first land acquisition was 300 acres near his father-in-law’s plantation. Just one week before Levi’s 1858 death, he made his last land purchase from his neighbor, Seaborn Hendrick Sr.

By 1853, Levi was teaching about 20 local children at a school on land that the Hendricks had donated for that purpose. The school operated only four months a year. Levi received $25 per month for teaching.

Levi and Elizabeth had two children survive to adulthood, Sarah Phillip “Sallie” and John Allen. A third unnamed infant son was buried in the Ware Cemetery less than a year before Levi himself died. A fourth child, born months after Levi died, also died in childhood, in 1860.

Levi knew his death was imminent when he prepared a will on July 20, 1858, and wrote, “…knowing that my body is feeble and being that my earthly life will soon be terminated…”. He died 18 days later and was buried in an elaborate brick-covered grave next to his infant son. Levi’s will noted the need to pay his debts and funeral expenses with proceeds from the farm. He asked his father-in-law, brother-in-law, and neighbors, including Seaborn Hendrick Sr., to appraise his real property and slaveholdings. Levi directed that they divide the land into even shares and split the slaves into three or four uniformly valued groups regardless of age or gender, to be divided among his heirs. Levi specifically noted that his daughter’s inherited property would be hers solely and not subject to any marriage contract. He willed his personal estate to his widow, including farm animals, wagon, notes, money, furniture, provisions, and household items. He willed his two gold watches and chains to his widow and requested that upon her death each of their children receive one of the timepieces and a chain. His widow and children were to equally share his books. Levi requested that his beloved wife “raise, board, clothe, and educate” their children. In the end, Levi’s property did not require division since his widow survived him for many years. Elizabeth and her three children remained on the plantation until 1860, when she married politician and plantation owner James Winwright Flanagan and moved to Henderson, the county seat.

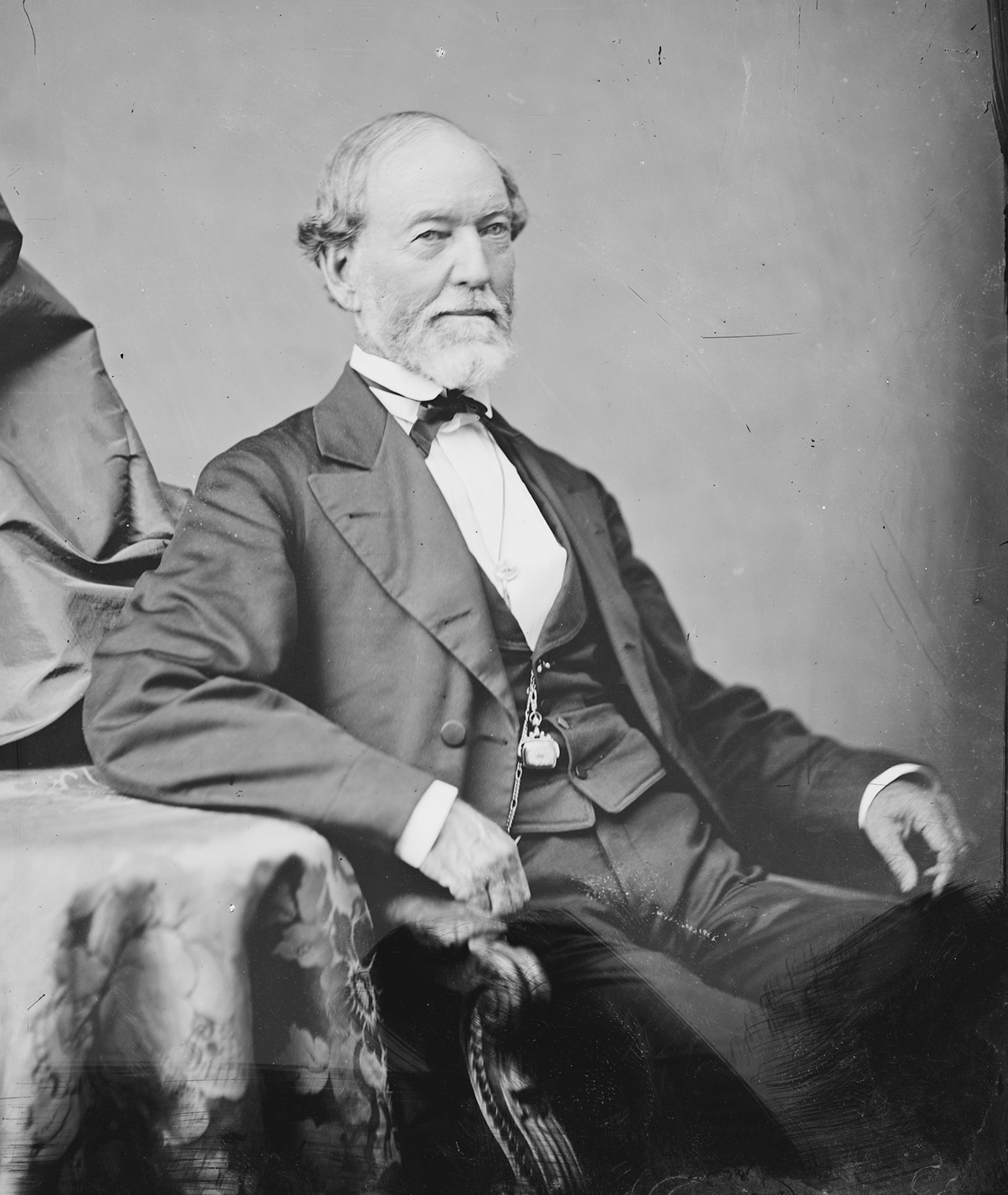

By 1860, Elizabeth was especially affluent. Her personal wealth afforded her children opportunities, including sending her daughter to college in Virginia. The union between the widowed Elizabeth and twice-widowed Virginia-born Flanagan was a likely partnership and became the longest-lasting marriage for both. His first two wives had each died in their thirties. This was Flanagan’s second May–December relationship, as his second wife was 17 years his junior and Elizabeth was 23 years younger. In addition to his plantation and political career, Flanagan was a land speculator, entrepreneur, and lawyer. He and Elizabeth probably crossed paths in the small town of Henderson, since both had achieved substantial economic wealth and were part of Rusk County’s affluent planter class. She held considerable economic power with her land and slaves, which remained her separate property as per state law. A few years after their marriage, the couple had two children in quick succession, Henry Clay and Yates Vinson, both of whom died in their late teenage years.

During the Civil War, the Flanagans resided in Henderson where they profited from the conflict and maintained his political stance, though he did not hold political office during this period. Flanagan established a tanning yard in Henderson and a tannery on the Ware plantation grounds. From these processing locations, Flanagan supplied large quantities of leather under contract to the Confederate government.

After the Civil War, Flanagan returned to politics, serving as a Texas constitutional representative, lieutenant governor, and U.S. senator. His politics are detailed in Historic Rusk County. During his tenure as lieutenant governor and U.S. senator, Flanagan, and possibly Elizabeth, lived at least part time in the state and national capitals. By 1877, the Flanagans had settled in Longview, Gregg County, Texas, where they resided until their deaths.

When Elizabeth Hinton Vinson Ware Flanagan died in 1882, the two surviving adult children from her marriage to Levi inherited her property, including the plantation lands, although the adult Ware children did not live there. Tenants likely occupied and cultivated at least some portion of the land. In 1891, John, by now of Gregg County, sold much of his acreage to his sister, Sallie. Sallie was twice married, her second husband being her stepbrother, Phillip Ware Flanagan. Although both Ware siblings and all of their progeny lived elsewhere, the plantation property remained in the possession of them and their descendants until 1970.