The majority of residents on the Hendrick and Ware plantations were enslaved African American children, women, and men. Their undoubtedly fascinating personal histories are not captured by the archival record, which only cursorily documents nameless enslaved blacks as property of the Hendricks and Wares. However, the African American experience on the Hendrick and Ware plantations can be envisioned through the archeology, slave censuses, and tax records, and by drawing on local ethnography and accounts of the lives of enslaved people from similar communities.

Rusk County Ethnographies

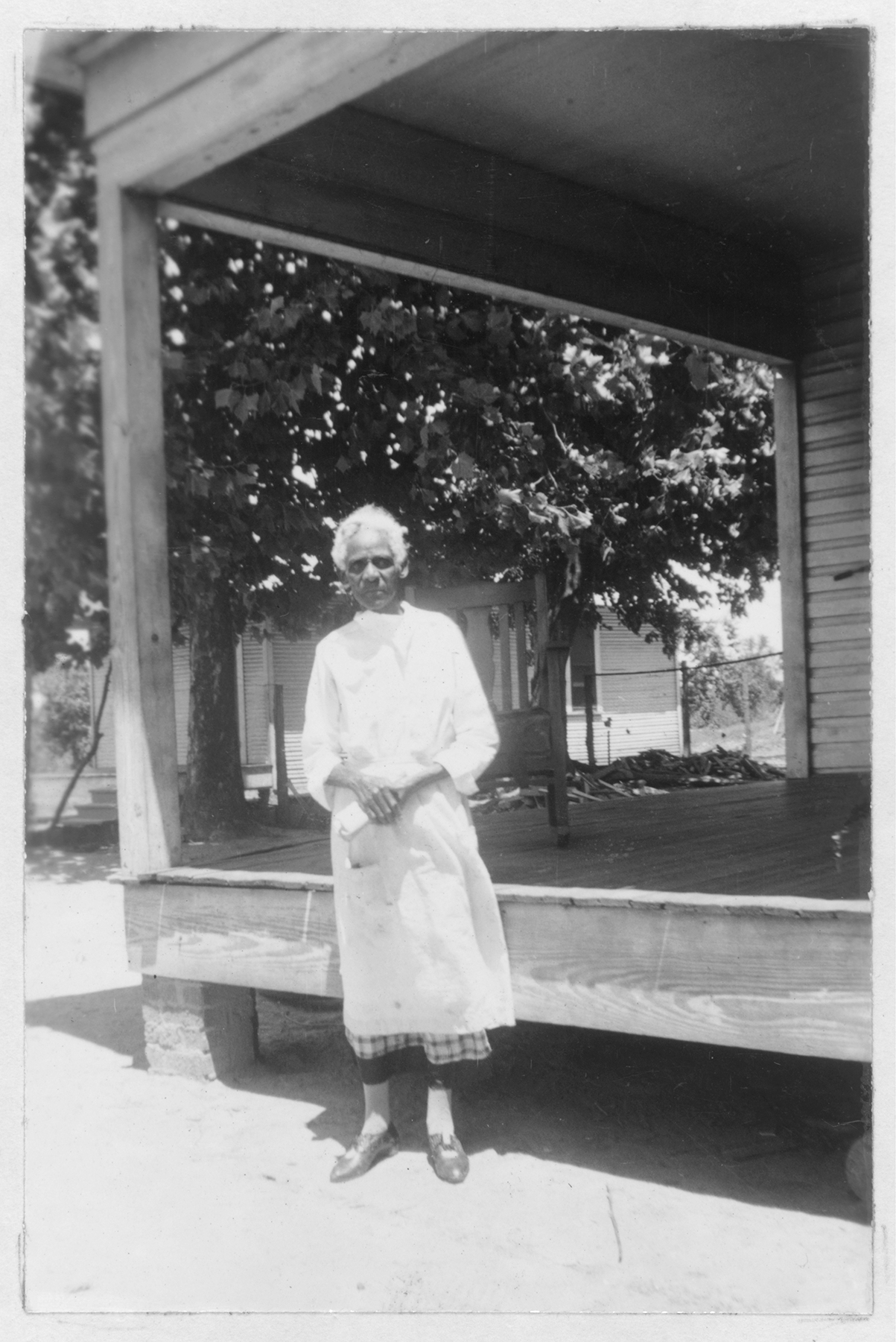

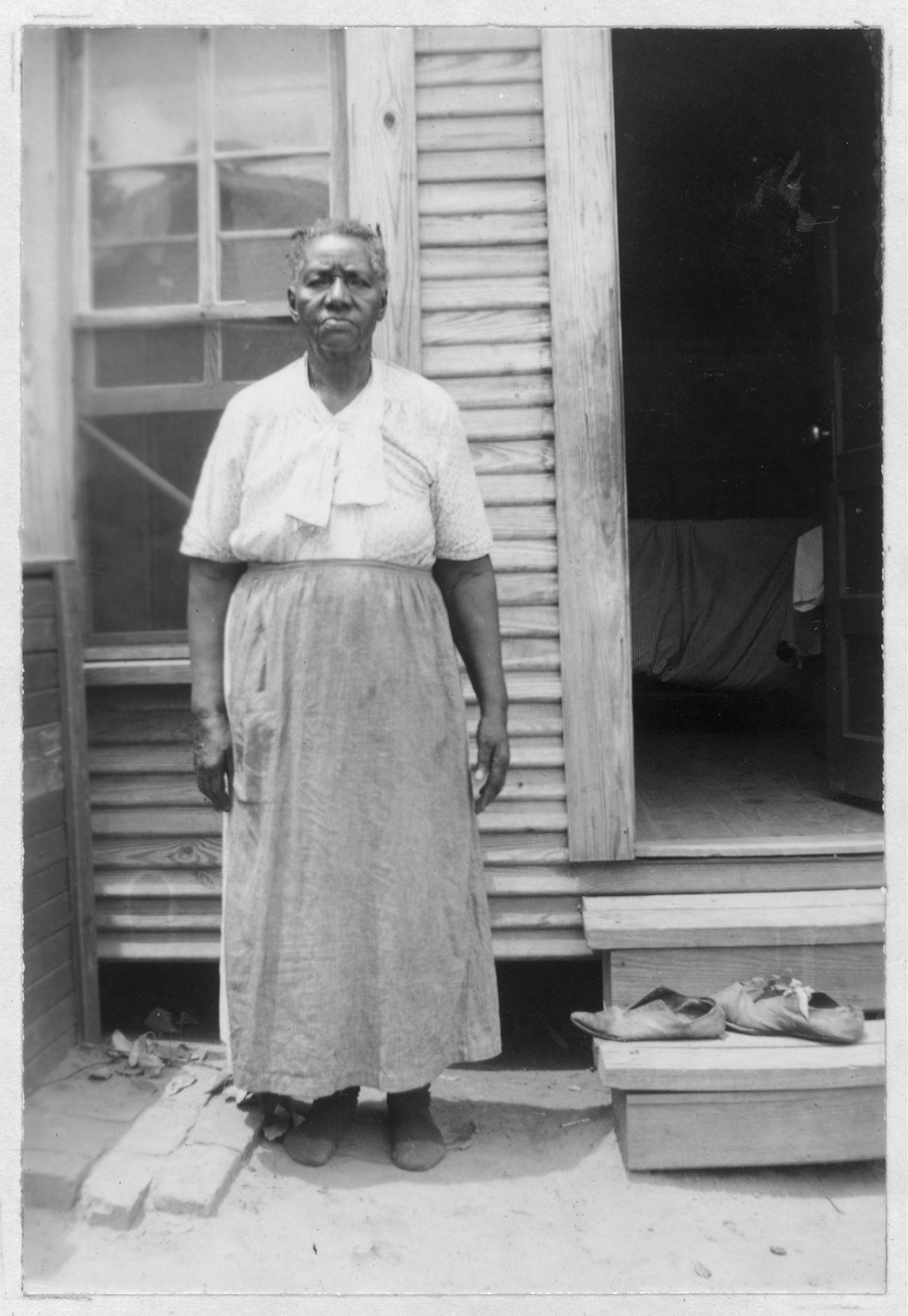

Stories from the lives of formerly enslaved Rusk County residents, in their own words, are particularly revealing. Though we cannot extrapolate their stories to the enslaved residents of the Hendrick and Ware plantations, these accounts provide a window into how enslaved African Americans on nearby plantations lived. The following ethnographies are from the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Texas, published in 1941.

Susan Rollins Merritt was born into slavery in Texas. Her father lived on one plantation and she, her mother, and her six surviving siblings lived on another. Merritt recalled the planter’s big log house on a hill overlooking the slaves’ little log huts huddled together in a field. They slept on mattresses made of baling sacks placed on bunks nailed to the wall. They wore the same clothes year-round and had plenty of grub. The slaveowner, Watt, made shoes, furniture, saddles, and harnesses, plus ran a grist mill and a whiskey still. “That man had everything,” according to Merritt. At the sound of the bell before daybreak, the people Watt enslaved went to the field and stayed there until dusk or dark six days a week. They toted water from the spring, cooked and ate supper, and were in bed when Watt tolled the evening bell at 9 o’clock. The children’s supper was a small piece of corn pone and a tin cup of milk. Adults had fat pork, greens, beans, and milk. On Sundays, Watt provided chicken, flour, and butter.

Watt had a slave driver who used a long whip on men, women, and children. Merritt worked in the big house most of the time, and her mistress frequently whipped, stomped, and beat her and made her walk through hot coals as punishment. Merritt reported that many Rusk County African Americans were not freed at Emancipation. When they attempted to find freedom, they were bushwhacked and shot or hanged in trees along the Sabine River bottom. Poignantly, Merritt noted that she did not know her age for sure, “but does you think I’d ever forget them slave days?” Merritt lived to be about 90 years old, passing away in 1938.

Another Rusk County freedman, Harrison Boyd (1843–1939), was born on the large Trammell plantation. The Trammells also held one set of Boyd’s grandparents, Jennette and Josh, and several of his siblings. The Trammells resided in a hewn-log house clad with weatherboard, and the slave cabins were log. Rations were distributed every Sunday, but the enslaved raised much of their food. They planted two bottom fields in corn that was shucked every fall. Two big cribs stored corn for use on the plantation, and five big cribs stored corn for sale. The plantation also had five wheat cribs and one for rye. They did not have a mill, so these grains were transported for grinding. Unlike Merritt’s experience on the Watt plantation, Boyd recalled that Trammell immediately fired his overseer after learning he had beaten an enslaved female.

In 1850, the Trammells enslaved 29 people, the year Millie Ann Moore Smith (1850–1938) was born. The Trammells already held her grandparents when they brought her mother from Mississippi to Texas, where she was born. Her father ran away from his Mississippi slaveowner and persuaded Trammell to buy him. Smith considered the Trammells the county’s richest family with the most enslaved people and land. The enslaved lived down the hill from the big house in a double row of log cabins. They had beds that her grandfather built, just like the beds he made for the Trammells. According to Smith, Trammell did not allow the overseer to administer whippings, but permitted him to tie people to a tree as punishment. Trammell spoke directly to the enslaved who had committed infractions. Smith explained her master would “never whip ‘em too hard, just enough to make ‘em behave.” A horn woke them before sunrise to work the plantation fields during the day. In the evenings they accomplished household chores, such as weaving, tending livestock, and other tasks. They had their own gardens, and her grandfather had Trammell’s consent to hunt and sell wild turkeys and hogs.

Anderson Boyd “A. B.” Edwards (1844–1946) and Manerva Cox Edwards (1850–1955) were enslaved on adjoining Rusk County plantations. After escaping slaveowners in Maryland and in Panola County, Anderson was purchased by James Winwright Flanagan, second husband of Elizabeth Vinson Ware. Manerva was enslaved with her mother and nine siblings by the Gants. In 1860, the Gants had two houses for their 10 enslaved African Americans. The Gants lived in a hewn-log house across the road from a row of quarters for the three enslaved families. Manerva’s mother was a weaver and made clothes for the plantation. The enslaved worked the fields until dusk and were in bed by 9 o’clock. They ate a lot of ash cake, which was cornmeal batter stuffed inside corn husks and baked in ashes. At corn-shucking time, they shucked all night, with a big dinner and whiskey to look forward to. Gant whipped the people he enslaved. Nearby were the Vinson (Elizabeth Hinton Vinson Ware’s parents) and Fry plantations, both of which sold people “chained together and drove off in herds by a white man on a horse.” They also sold infants. The Edwards both worked at their respective plantations for three years after the Civil War concluded.

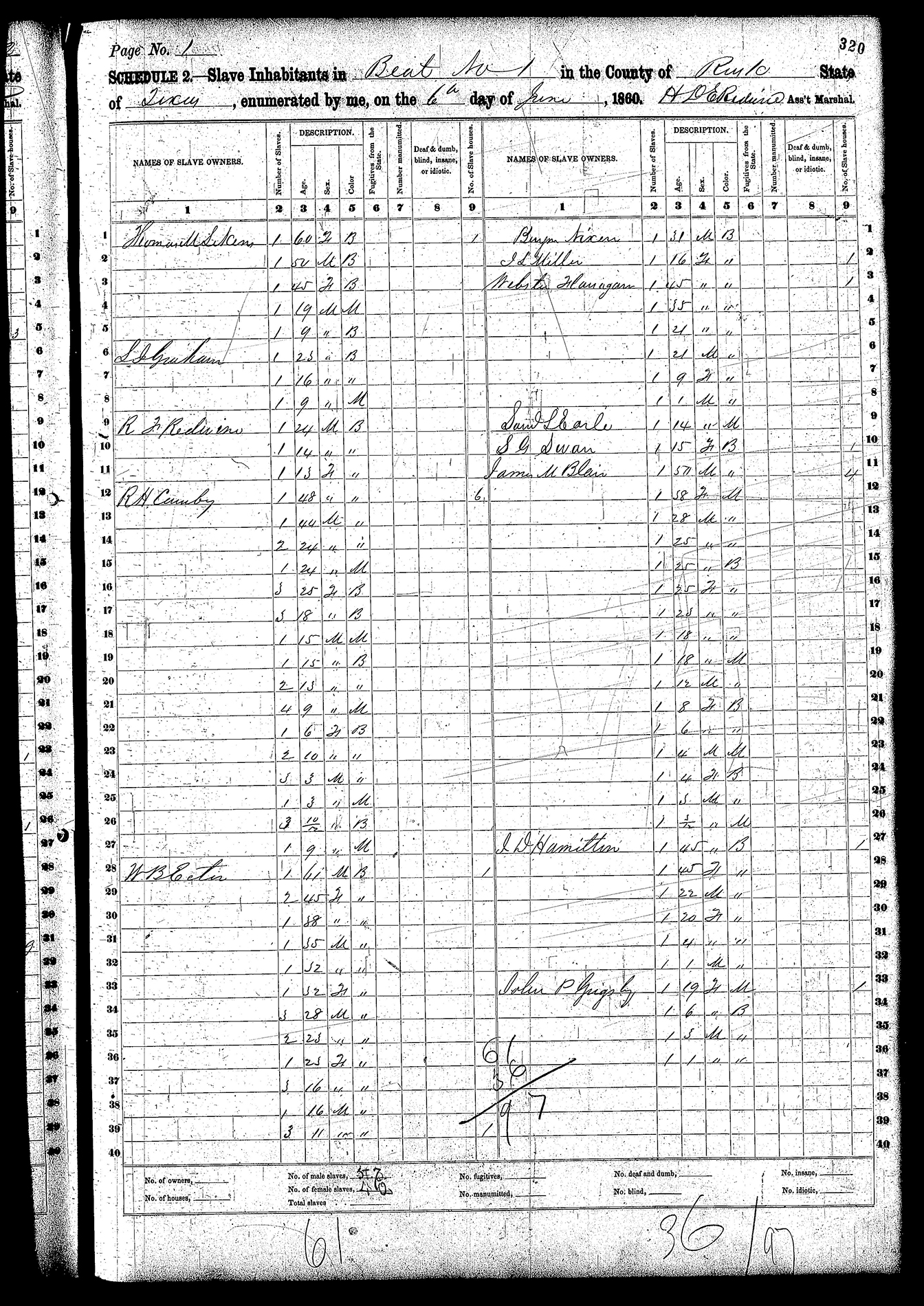

From the Archives: Slave Censuses and Tax Records

Federal slave census and county tax records document how many enslaved African Americans lived on the Hendrick and Ware plantations. The federal decennial manuscript censuses for 1850 and 1860 list the slaveowners’ name and the age, gender, and skin color (that is, race) of each enslaved person. No names of the enslaved were recorded. The 1860 census also records the number of dwellings for the enslaved on each plantation. From these data, we can reconstruct the demographics of the enslaved African Americans on the Hendrick and Ware plantations.

Ad valorem tax and federal manuscript census records each have biases, deficiencies, and advantages—they are reliable and capricious in opposing yet complementary respects. Annual tax records are useful to the historian because they provide a constant view, but some slaveowners underreported the number and value of people they enslaved to lower their assessment and payment. Also, enslaved infants and elderly were considered less valuable since their labor contributions were minimal, and they were often excluded. It is estimated that assessors consistently undercounted the enslaved population by 10 to 20 percent. Conversely, slaveowners were likely to precisely report the number of and specifics about people they held to census takers, since the enslaved population counted toward the state's congressional representation under the Three-Fifths Clause. In the U.S. Constitution, this clause declared that an enslaved person counted as three-fifths of a free citizen towards representation, and consequently advanced slaveowners' political interests. Censuses were only taken every 10 years, so these records provide only decadal snapshots.

When the Hendricks moved onto the plantation in the late 1840s or early 1850s, they may have brought enslaved African Americans with them from Georgia or Alabama. By 1850, they held 9 people: 2 adult females and 2 adult males, 3 older children/teenagers, and an infant. Age ranges indicate the possibility of several family groups. Except for a 12-year-old mulatto male, all were denoted as black.

By 1860, the community of enslaved African Americans on the Hendrick plantation had grown to 23 people living in 4 houses—6 adult females and 2 older female children, 7 adult males, and 6 young children and infants. By 1864, the Hendrick slave community had declined to 19 people. In 1865, enslaved people were not reported in tax records. It is not known whether the formerly enslaved community remained on the plantation as paid labor, made new lives locally or elsewhere, were held illegally, or were victims of other forms of violence, such as that described by Rusk County freedman Susan Rollins Merritt.

The name of just one African American who lived on the Hendrick plantation is known today. Littleton Watters was purchased by Hendrick Sr. at a public auction in Henderson for $1,160 in 1860 and was described as a dark-colored man about 30 years old. Littleton was registered to vote by 1868, and by 1870 he and his family were farming in Rusk County’s Third Precinct. His wife, Ann E. Watters, and four children—two born before into bondage and the other two born free—were all native Texans. Both he and his wife were literate.

The Wares held many more people in bondage than the Hendricks when they first arrived in Rusk County, and it is likely that many enslaved African Americans travelled with them from Tennessee. In 1851 and 1852, the enslaved community on the Ware plantation consisted of 25 people. In 1853 they numbered 23, and in 1854 and 1855 they numbered 22. These numbers increased thereafter, to 27 slaves in 1856 and 1857 and 30 in 1858, when Levi Hill Ware died.

The death of a slaveowner could provoke intractable upheaval for the enslaved, causing an already unpredictable life to become even more volatile. Few enslaved Texans were awarded manumission (release from slavery) upon their owner’s death. Instead, they were typically divided into groups based on their value, not on age, gender, or familial ties. Ware’s will directed just such a division among his heirs. Because his widow lived for many years, the division of the Ware African American community did not occur as outlined in his will; the enslaved people of the Ware plantation may have continued to be held by his widow.

After Elizabeth Vinson Ware married wealthy planter and politician James Winwright Flanagan, the couple together enslaved more than 100 African Americans. It is unclear how the enslaved may have been grouped across the Flanagans’ numerous properties. If the African Americans enslaved by Elizabeth lived at the Ware plantation, then in 1860 the Ware community consisted of 5 adult females and 5 adult males, 1 of whom was without speech (“deaf and dumb”), 9 teenage females and 5 teenage males, 4 older children, and 9 very young children.

Enslaved African Americans faced myriad challenging circumstances stemming from the community-fracturing nature of being treated as property. The likelihood that enslaved people could sustain nuclear families was slim, but in some situations it did occur. A particularly difficult condition was that of a single enslaved woman with young children of her own and no other adult in the household. These women had to manage both their workload in the fields of house, rear their children, and potentially rear children for their enslavers.

Houses and Belongings

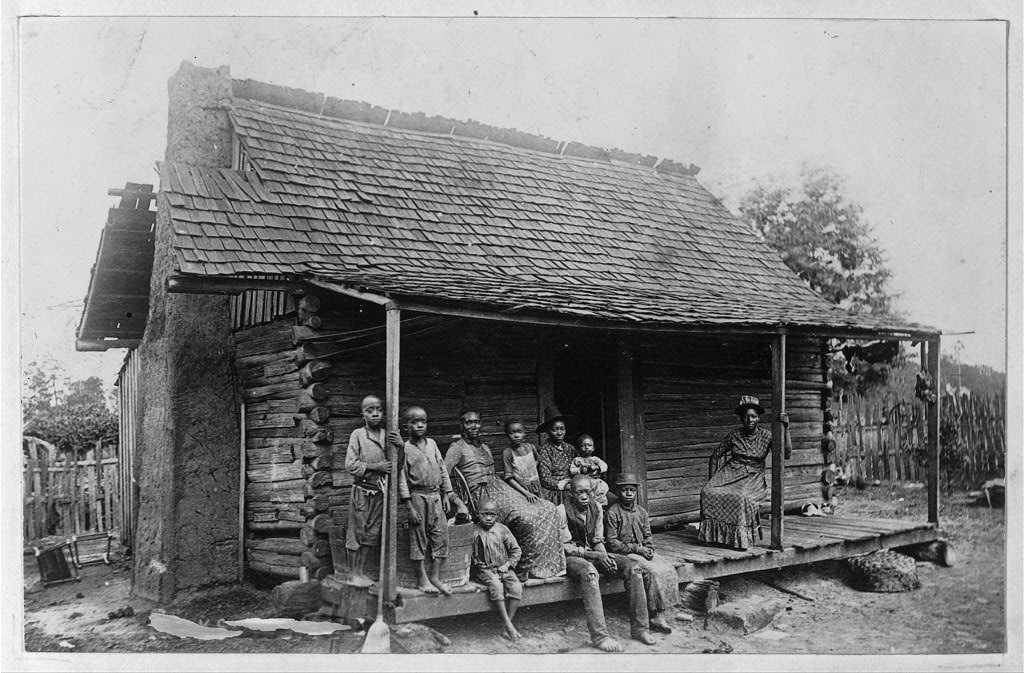

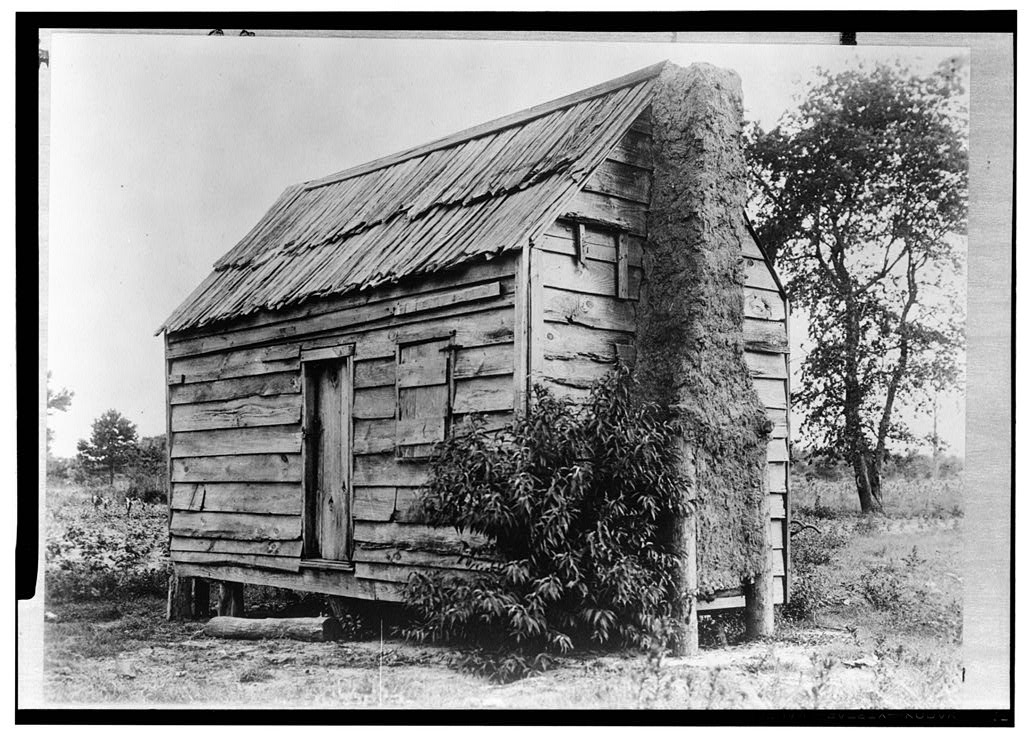

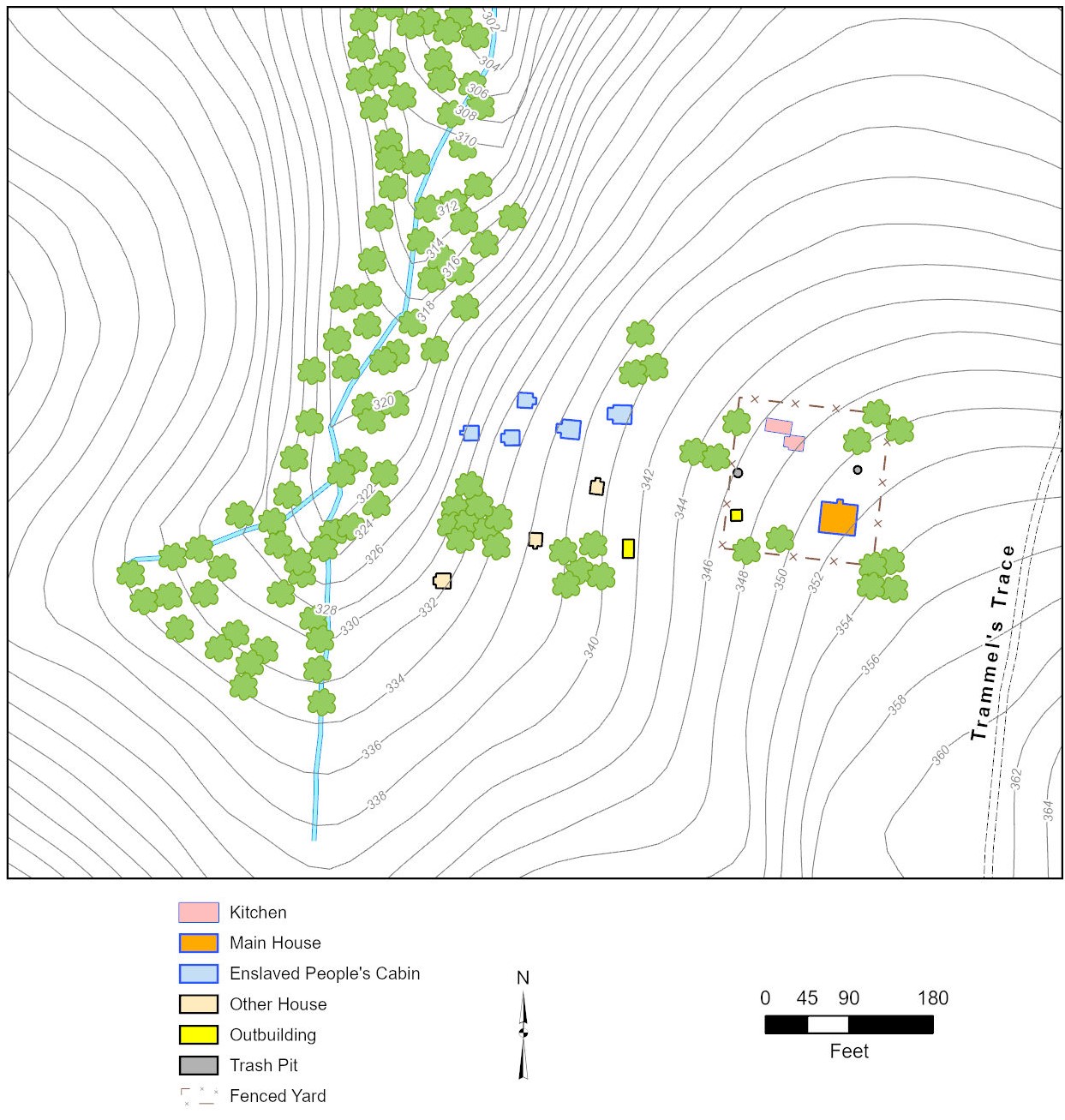

Accommodations for enslaved African Americans varied in terms of construction and quality. The enslaved lived apart from owners, but on many plantations the distance separating the two worlds was small. Evidence from excavations at the Hendrick and Ware plantations demonstrate that slave quarters were within the main plantation cores, a relatively short walk from the planter’s house. Most of the archeological information about their dwellings comes from the Hendrick plantation, where extensive excavations occurred.

Archival records indicate that Hendrick had 4 cabins for 20 enslaved people in 1860 and that the widowed Elizabeth Vinson Ware had 7 houses for 39 people. Archeological evidence indicates Hendrick added a fifth dwelling after 1860. At the Hendrick plantation, the cluster of 5 dwellings was in a 200x215–foot area, downslope approximately 160 feet from the planter family's house and kitchen. The cabins were in a staggered east-west row spaced about 20–30 feet apart. Most were on or just above ground that sloped steeply down to a spring-fed creek. Because of the slope, these were poorer building spots than the locations selected for other buildings, and the dwellings were not as well built as the big house.

One of these 5 log cabins was about 16x16 feet, and 2 were a bit larger. The others undoubtedly were similar, but too little was left when they were excavated to be certain. They had sandstone rocks supporting their corners, and four had plank floors that sat off the ground slightly. One cabin may have had a dirt floor or wood planks resting directly on the ground. Each cabin had a chimney on its west or east wall. The chimneys themselves were made of mud and sticks, but the fireplaces beneath them were built from sandstone rocks and some bricks. In at least one, the hearth in front of the fireplace consisted of flat sandstone slabs. The cabins had one or two windows with glass panes in them, and each probably had a single door that opened to the north or south. At one, the occupants laid a pavement of bricks outside the door to create a tidier work and living space, but there is no indication this space

had a roof covering or that any cabins had porches.

On average, four or five people lived in each of these dwellings. This is where they slept, cooked and ate most of their meals, and conducted many other daily activities. Recovered artifacts offer evidence of these activities: sewing, maintaining garden tools and horse tack, maintaining guns and making lead shot for hunting, children’s play, reading and writing, drinking alcohol, smoking tobacco in clay pipes and dipping snuff, caring for the sick, and making music.

The dwellings of the enslaved plantation residents contained upholstered furniture, tables or chests with drawers, trunks for storage, andirons to hold logs in the fireplaces, oil lamps, and even padlocks to keep their things secure. They had cooking pots, ceramic dishes and utensils for eating, glassware for drinking, and stoneware crocks for storing food. Personal possessions included pocketknives, hair combs, parasols or umbrellas, jewelry, and musical instruments, specifically, mouth harps.

A few artifacts found at the Hendrick plantation hint at ritual and spiritual practices in the home, which may have been intended to influence the future, offer protection, harm others, or promote heath and well-being. The most noteworthy, yet enigmatic, of these was a metal can containing a nail and two chicken bones which someone buried in the ground behind one of the cabins. Possible charms found by archeologists include a small lead star, a piece of a stalactite, two worn coins, and a brick fragment shaped like a Native American dart point. Similar evidence for African American spiritual life has been found at many other excavated sites of enslavement in the American South.

Clothing

Slaveowners typically provided clothing to the people they held captive. On larger plantations, it was not uncommon for men to be issued two pairs of pants and two shirts and for women to receive two dresses and undergarments annually. Coats, hats, and shoes were supplied as needed. House servants were usually better clothed than field hands. Clothing items could be homemade, of buckskin, homespun materials, or made from purchased bolts of inexpensive, durable fabric. Clothing was often sewn by the mistress, overseer’s wife, an enslaved seamstress, or an enslaved woman for her own family members. Sewing implements at the Hendrick plantation dwellings indicate clothing was mended, if not made, at on the plantation.

Diet

Food allowances and distribution differed considerably across the American South. Some planters dispensed uncooked food for the enslaved to prepare on their own and others provided cooked meals. Individual or communal gardens were common, and some enslaved were allowed to hunt, fish, or raise chickens for eggs and meat.

Corn grown on the Ware and Hendrick plantations was for profit and for consumption, and it was undoubtedly a dietary staple of the enslaved. To supplement this, the Wares' enslaved would have raised vegetables, especially peas and beans, greens, potatoes, and sweet potatoes, which supplied the potential for balanced nutrition. In contrast, the Hendricks' enslaved produced enough corn to sell and nourish the plantation residents and livestock but raised lower than normal levels of vegetables.

The diet of the enslaved may have been supplemented with the plantation’s produce, or they may have had their own gardens; there was ample room for garden plots on the flatter ground upslope from the dwellings at the Hendrick plantation. Archeological evidence confirms they grew peaches and collected wild plants like grapes and elderberries. Tobacco seeds at one slave cabin suggest they grew this plant, which corresponds with the large number of pipe fragments found during excavation.

Protein in the diet of the enslaved was primarily rations of pork and beef. The remainder came from wild game, including deer, opossum, rabbit, squirrel, and raccoon, turkeys, other birds, and catfish. Gun-related artifacts around the cabins suggest the slaves hunted game.

Interestingly, the cabin nearest the Hendrick’s detached kitchen had few butchered animal bones or other evidence of cooking, leading to speculation that this was the enslaved cook’s dwelling and that she ate her meals in the detached kitchen by the big house.

Labor

Most enslaved African Americans were engaged in agricultural production, but they undertook many other types of labor. Men might be stone masons or pump makers, herdsmen or livestock handlers, and women were often given roles of cook, laundress, and midwife. Few men worked as cooks, and those who did were likely under the supervision of a woman. The enslaved built houses for themselves and their owners, including such elements as handmade bricks from local clay for the Hendricks' big house piers and fireplace. Even the youngest were expected to accomplish easy tasks like carrying water and pulling weeds.

Nature ordered some agricultural activities, slaveowners determined rules on their plantations, and slaves shaped their lives around these edicts. Seasons and days of the week dictated procedures that included when to wake and sleep, what and how much to eat, and planting schedules. Slaveowners or their hired overseers or drivers directed how far apart to plant crop rows and how much cotton, corn, or other crop each enslaved should pick during harvests. The enslaved, in response to the hierarchical social structure, established practices for interacting with their slaveowners, other whites, and peers.

Some planters hired white overseers to manage and monitor the activities of the enslaved. In these situations, most slaveowners had an extremely impersonal relationship with the people they enslaved. Overseers tended toward severity and cruelty to achieve maximum production and earnings. Yet the enslaved held on plantations with an overseer were likely to have more opportunities to shape their lives under these more impersonal conditions. Elizabeth Ware Flanagan hired an overseer to manage her plantation after she remarried. In 1860, that overseer was a 25-year-old who lived on the plantation with his wife. Hendrick may not have had an overseer since by 1860 he had 18- and 22-year-old sons who could have served in that role.

The economic value of enslaved people was measured by their capacity for hard labor. For enslaved women, their capacity to bear children also increased their value. Although the Wares held many more people than average, their market value was only a few dollars more than the average—an indication that several individuals they held were considered less valuable. Even though the Hendricks held slightly fewer enslaved than the local average, the per capita value of the people they enslaved was the highest in the area, suggestive of a strong group of workers.

In Sickness and in Health

On many plantations, appealing to a medical doctor was a last resort reserved for averting loss of life and productivity. Some slaveowners implemented practices like administration of an annual calomel-and-salt tonic. When illness arose, African Americans would often first turn to their own social network and consult a folk healer. The untrained, but likely experienced, mistress or overseer’s wife was usually the next option. These women addressed medical needs with homemade plant-derived medicines to cure maladies and prevent illness.

More serious health issues benefited from a doctor’s oversight. For those whose slaveowners inflicted physical damage through overworking, branding, shooting, or flogging, a physician was often required to care for serious injuries, as were more severe accidents and illnesses. Because Hendrick was a physician, the people he

enslaved may have had better access

to health care than many.

Though slaveowners could, in theory, minimize need for a physician and maintain a healthy and productive work force by providing nutritious food, sufficient protective clothing, and dry shelter with appropriate ventilation to the enslaved, this was usually not the case. As previously described, enslaved people often had to supplement their rations by hunting and foraging, clothing was often limited to one or two sets a year, and dwellings were cramped.

Cemeteries

The Hendrick and Ware plantations each had a small African American cemetery. The cemetery started by African Americans at the Hendrick plantation, probably in the 1850s, is on top of a hill. In 2008 when archeologists visited this cemetery, 12 grave markers were observed as well as 7 depressions representing unmarked graves. Scattered now-feral ornamental plants were growing within the central portion of the cemetery. It is likely that people who died on the plantation were buried here, with their graves having sandstone or wood markers that have long since rotted. Freedmen who remained in the area continued to use the cemetery after the Civil War, and other African Americans who moved to the vicinity also buried family members there.

The African American cemetery at the Ware plantation is on a small ridge overlooking the confluence of two small streams. This cemetery probably was first used in the 1850s and may have been used last in 1898. When archeologists recorded it in 2008, it had not been maintained for many decades. Only 8 graves in a relatively large area were marked, but based on the distances between known graves, it was estimated that the cemetery has at least 15 to 20 burials.

None of the people with headstones bearing names are known to have been enslaved by the Wares, and two were born too late to have been enslaved. However, people who were enslaved on the Ware plantation may be buried in numerous unmarked graves. As at the Hendrick Cemetery, it is likely that freedmen who stayed in the area and their descendants continued to use the burial ground.