The area that would one day become Rusk County was settled by American Indians thousands of years before the arrival of Old World explorers. Not far to the north of the future site of the Hendrick and Ware plantations, the Nadaco Caddo were encountered in 1542 by the remnants of the Spanish Hernando de Soto expedition near a large Caddo village. The Spanish called the place and the people they met there Nondacao, which comes from the Caddo word “Nadaakuh,” translated as “the place of the bumblebee.” This particular village was established about 250 years before the de Soto expedition encountered it, and was abandoned for 150 years before the Hendrick and Ware plantations were established. The village site was probably known to locals in the nineteenth century, since the three temple mounds the Nadaco Caddo erected there were still standing, as they are today.

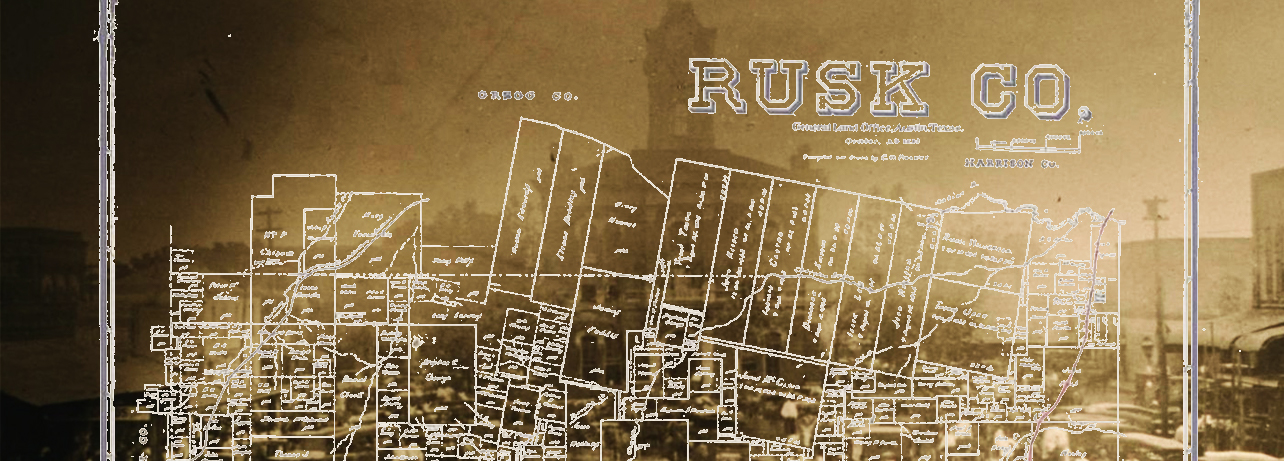

Though the Spanish claimed this territory (1690–1821), they never built permanent settlements in far northeast Texas. It was not until 1829, under Mexican rule (1821–1836), that the first land grant was made in what would become Rusk County, then part of the Mexican Government’s Nacogdoches District. During the tumultuous next 15 years—which saw the Texas Revolution (1835–1836), the formation of the Republic of Texas (1836–1845), and Texas’s annexation by the United States (1845)—several land-grant surveys within the Ware and Hendrick study area were patented to private land holders. As was typical across Texas, few of these early landowners resided in Rusk County—most used their land grants speculatively, selling swaths of land to incoming transplants from the southeastern states.

An exception to early land speculation in the future Rusk County was the Walling family, who started a community on the Sabine River during the period of Mexican rule. Walling’s Ferry (later renamed Camden, and most recently, Easton), developed around a ferry crossing built by John C. Walling Jr. near his home on the Sabine River, not far from the future Ware and Hendrick plantations. In 1844, a Louisiana-born couple joined the Walling family and opened a tavern and hotel on the north bank of the crossing.

After independence from Mexico, settlers flocked to the new Texas Republic. Among them was a contingent of interrelated Catholic families from Missouri who settled on land that would later become the Hendrick and Ware plantations. Because these Missourian migrants arrived in Texas before 1840, they were entitled to headright land grants from the Republic, and the early land surveys bear their names. The Benjamin Ellis and Edward Simon Surveys became the core of the Ware plantation, and the Jacob Foulks and William Simon Surveys became the nucleus of the Hendrick plantation.

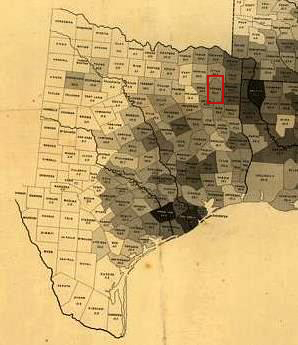

After Texas achieved statehood in 1845, more Euro-American migrants permanently settled in the area. Many of them brought enslaved African Americans with them. In 1850, almost half of the population of Texas resided in its northeast region. That year enslaved African Americans made up approximately a quarter of the population of northeast Rusk County. By 1860, enslaved African Americans were the majority of local occupants, representing 59 percent of northeast Rusk County’s population.

The Seaborn and Frances Hendrick family were in Rusk County by 1848, and the family of Levi and Elizabeth Ware had moved to Rusk County by the early 1850s. It is likely that the Wares brought numerous enslaved African Americans with them from Tennessee. It is less clear whether the Hendricks brought enslaved people to Texas from their previous residences in Georgia and Alabama.

Economy

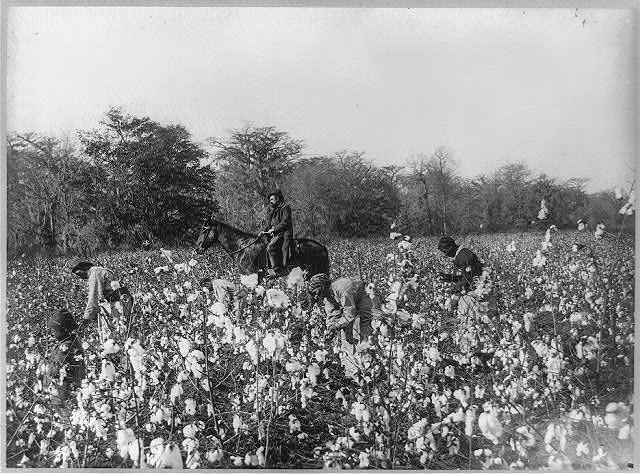

Enslaved African Americans became the backbone of Texas’s nineteenth-century agricultural economy. They cleared the forests, cultivated the land, and built new homes for their owners' benefit. Before the Civil War, most agricultural products in the state were from northeast Texas. In 1850, 88 percent of northeast Texans were farmers, and by 1860, a whopping 92 percent of the population farmed. Rusk County farmers produced corn, peas and beans, sweet potatoes, oats, and cotton; they raised beef cattle, dairy cows, sheep, and swine. Draught animals—the horses, mules, asses, and oxen that hauled equipment like ploughs and cultivators, or vehicles like wagons and buggies—were also raised. The northeastern region of Rusk County, where the Ware and Hendrick plantations were, had even higher agricultural yields than the rest of the county.

Shopkeepers, merchants, saloon operators, doctors, teachers, preachers, mechanics, ferry operators, and other tradesman were critical to supporting the rapidly growing population of Rusk County. Many free men were farmers and held other occupations. The Ware and Hendrick patriarchs both had professional lives outside the farm—Levi Hill Ware was a teacher and Seaborn Jones Hendrick Sr. was a doctor. Ware taught at the one-room schoolhouse on or near the Hendrick plantation. Little is known about Hendrick Sr.’s medical practice, though it is presumed that his skills were called upon both on the plantation and in the local community. Rusk County women also worked, holding positions such as teachers, seamstresses, tailors, laundresses, nurses, and matrons.

An Introduction to the History of Slavery in Texas

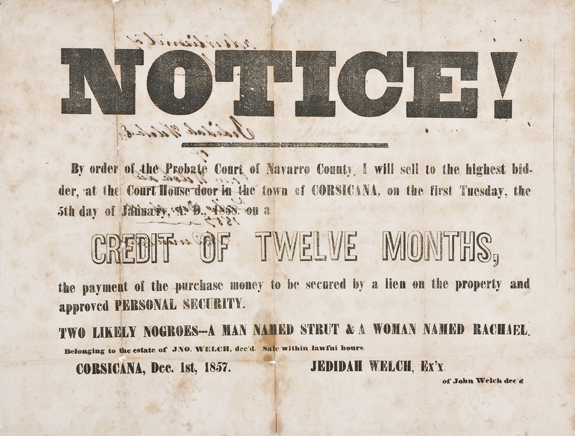

Centuries before Texas statehood, the Spanish participated in and profited from the African slave trade. However, Spaniards brought few enslaved Africans to Texas, which was still a far-flung Spanish territory in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Missions and military forts were the most common settlements on the Spanish Texas frontier. Even the largest of these, San Antonio de Bexar, had only a couple dozen enslaved people recorded in the late eighteenth century. Under Spanish slave law, Siete Partidas, the enslaved had formal legal rights. These included the rights to marry, hold property of their own, have legal protection and recourse from cruel masters, not be separated from their children, buy family members, and sometimes even free themselves through arrangements with their masters. Such rights stood in contrast to American concepts of chattel slavery, in which the enslaved were considered property to be bought, sold, and otherwise bent to their slaveowners’s will.

The arrival of Stephen F. Austin and the 297 Euro-American families he brought to Texas was a turning point in Texas’s history of slavery. Arriving in 1821, Austin and the Old Three Hundred, as these first families are known, settled in eastern Texas under a Spanish empresarial grant Austin inherited from his father. These families brought hundreds of enslaved African Americans to Texas from the southern United States. Though Austin’s land grant was made by the Spanish government, which permitted slavery, the Old Three Hundred soon found themselves to be Mexican citizens rather than Spanish. The Mexican Revolution and subsequent Mexican independence presented challenges to slaveowners in Mexican Texas, because many leaders of the Mexican Revolution opposed slavery. Though slavery was initially permitted under Mexican law, free blacks were afforded the same rights and citizenship status as any other citizen. As time went on, Mexican policy became increasingly anti-slavery, and in 1827 declared it illegal to bring slaves to the country. However, many immigrants disregarded Mexican laws prohibiting slavery or forced the people they enslaved to sign documents classifying them as indentured servants—essentially, slavery by a different name.

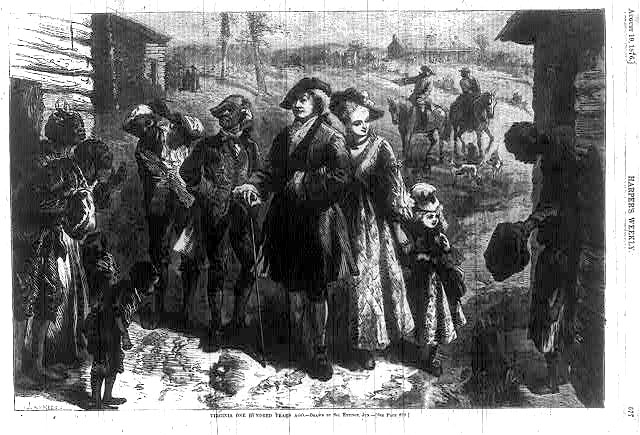

After the Texas Revolution (1835–1836)—the overthrowing of Mexican rule instigated by Euro-American migrants from the southern United States and some Tejano (Texas Mexican) slaveowners—more Euro-American southerners migrated to the Republic of Texas. The Republic not only upheld the institution of slavery, but the Texas constitution also stated that free blacks were not permitted to live in Texas unless the state Congress granted special permission. After the United States annexed Texas in 1845, slave-owning southerners poured into the new state in even greater numbers, among them the Hendricks and Wares.

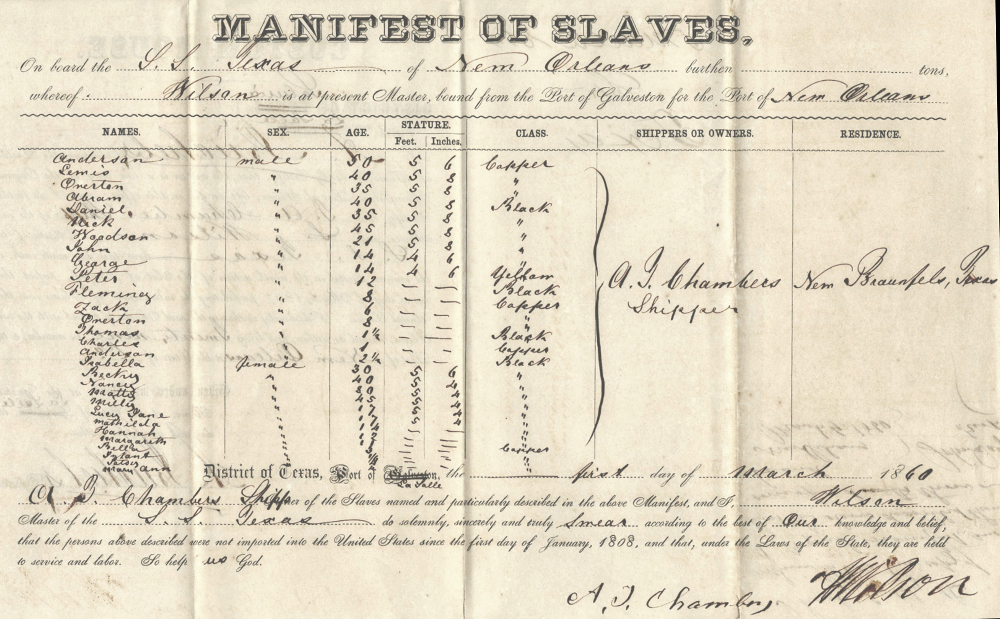

The Atlantic slave trade was outlawed in the United States by the early nineteenth century. It was not illegal in Cuba at that time, and human smuggling to Texas via Cuba continued well into the 1830s. By the mid-nineteenth century, most enslaved African Americans in Texas accompanied their slaveowners from elsewhere in the American South or were born into bondage in Texas.

Texas seceded from the United States in January 1861, joining the Confederate States of America in February. Secession was a heated issue, and many Texans opposed it, including some slaveowners and then-Governor Sam Houston. By March 1861, the Civil War (1861–1865), which would become the deadliest war in American history, had officially begun. In 1863, midway of the war, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, mandating that the rebellious Confederate states free the enslaved people within their borders. Under the Texas Constitution of 1861, slaveowners could not legally free an enslaved person. It was not until 1865 that the Confederate armies surrendered, Congress ratified the 13th amendment to the United States constitution, abolishing slavery across the country, and enslaved Texans recieved the belated news of their emancipation.

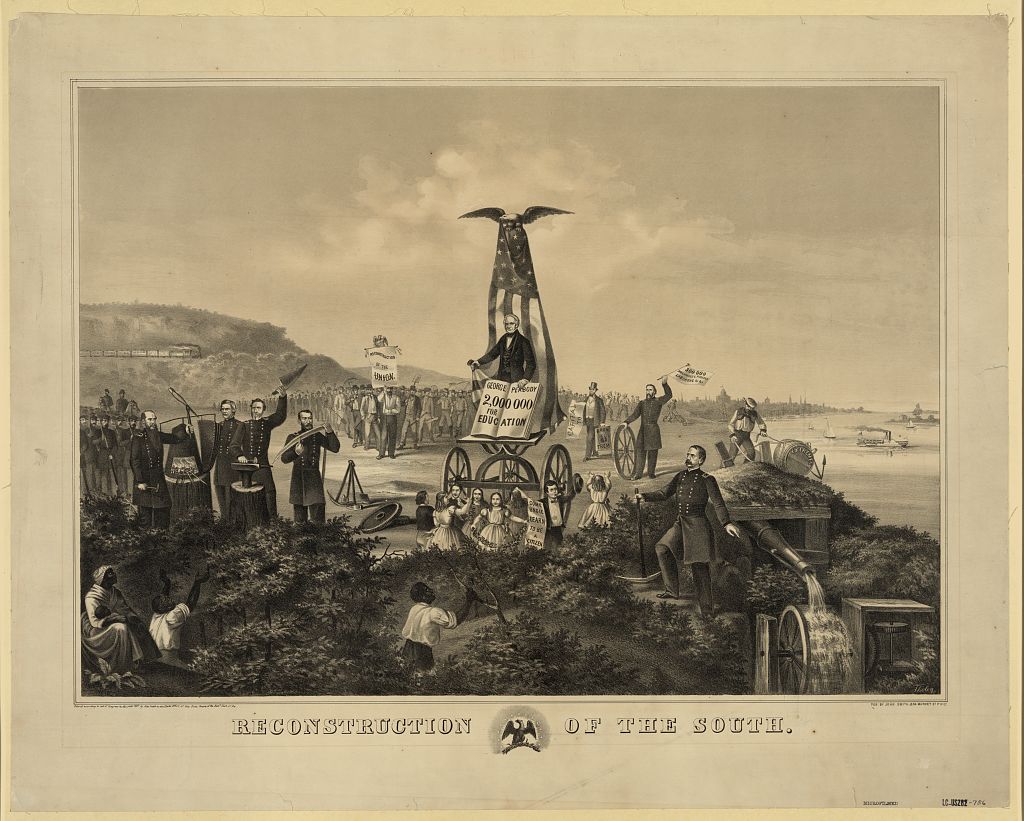

The Reconstruction period (1865–1877) that followed the Civil War was marked by federal attempts to control and reintegrate the Confederate states into the Union and to support and integrate previously enslaved African Americans, known as freedmen, into free society. Texas was fully readmitted into the Union in 1870. Reconstruction saw pointed resistance to these efforts, including the rise of secret white supremacy groups that terrorized freedmen and their supporters, and the subjugation of African Americans through tenant farming, sharecropping, and convict-leasing agreements which perpetuated cycles of poverty and oppression. Ultimately, Reconstruction efforts failed abysmally. The subsequent period—known as the Jim Crow era—saw intensified oppression of African Americans through state and local policies, social segregation, and both sanctioned and covert violence.

See the TBH Ransom and Sarah Williams Farmstead: Historical Context section for additional information about the history of slavery in Texas and the continued oppression of African Americans after the Civil War.

Rusk County Slaveowners and Enslaved

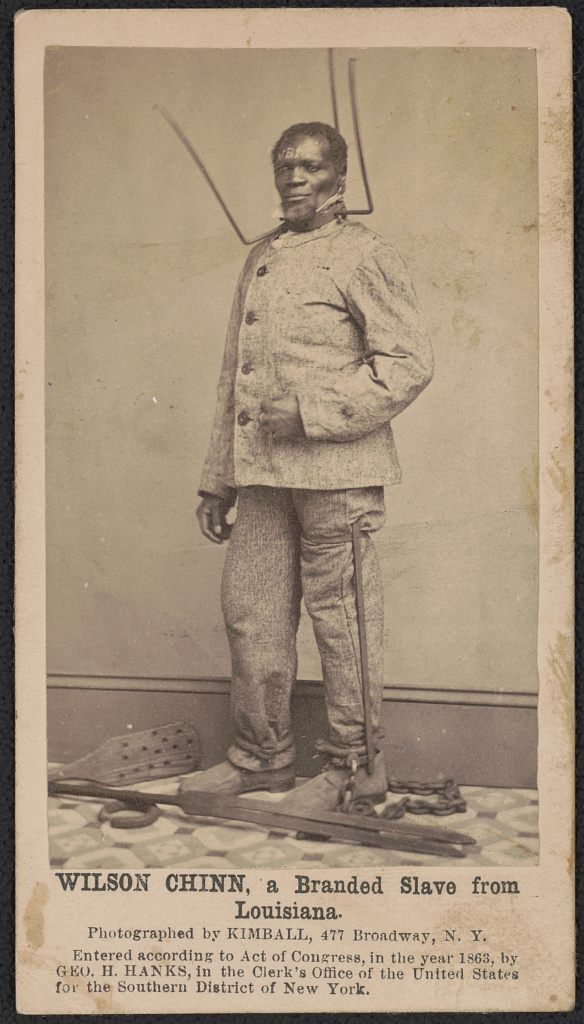

Most Rusk County slaveowners were land-owning Euro-American yeoman farmers who relied heavily on the labor of their families and typically 10 or fewer slaves to farm properties of about 150 improved acres or less. A minority of slaveowners were planters, who farmed larger areas and managed from afar. Wealth was concentrated among a very few planters who controlled a disproportionate portion of agricultural assets. This inequality permeated antebellum Texas, with the northeast region having a higher disparity than the rest of the state. Despite class differences, the practice of owning slaves had universal attributes. Chief among these was force—degrees of persuasion and punishment that ran the gamut from threats to physical violence—intended to exploit and control the enslaved.

The Ware and Hendrick families typified the dominant planter class in Antebellum Texas—they were both slaveowners and natives of the lower South. Their plantations were medium-sized and prosperous. In 1850, the Wares were near the low end of the spectrum of the wealthiest planter families, and the Hendricks were on the high end. As time progressed, the Ware plantation grew to be the wealthier operation of the two. The Hendricks enslaved 9–20 people and the Wares enslaved 22–30, with the number of enslaved on each of these plantations increasing over time.

The scant information collected about enslaved African Americans on slave censuses and tax records consists of skin color (black or mulatto), age, sex, disability (if any), taxable value, and the name of their slaveowner. The names of the enslaved were not recorded in these documents. The 1850 census data indicate that approximately 90 percent of the enslaved in northeast Rusk County were black and the remainder were mulatto.

The average age of the local enslaved population was just 18 years old. People between the ages of 13 to 40 made up about half of the population. The next-largest segment was youths, from infants to 12-year-olds, who represented 42 percent of the enslaved population. Remarkably, only 6 percent of Rusk County African Americans in 1850 were older than 39 years of age. Relative to today, life expectancies were shorter for people of all races and classes during the antebellum period, but enslaved blacks had a shorter average lifespan than the free white population.

The enslaved population of Rusk County experienced its highest rate of growth between 1850 and 1860, and the population continued to increase significantly during the Civil War. The last slave census taken, in 1860, counted 6,133 African American children and adults in Rusk County. That year, only one “colored” Rusk County resident, a male between the ages of 30 and 40, was listed as free. Compared with other counties in Texas, Rusk County had a large population of enslaved people. The highest concentration of Rusk County’s enslaved lived and labored in the northeastern part of the county. In 1860, 59 percent of northeast Rusk County residents were enslaved African Americans, compared to 39 percent of the county as a whole.

In the nineteenth century, the enslaved people of Texas were culturally and ethnically diverse, and undoubtedly this was true in Rusk County. The enslaved population likely included African Americans transplanted from myriad locations in the southern United States, African-born people, for whom the United States and its customs must have been wholly foreign, and people of mixed ancestry—commonly African, Native American, and European descent. Such a diversity of peoples resulted in creolization of cultures.

Civil War and Postbellum Economic Turmoil

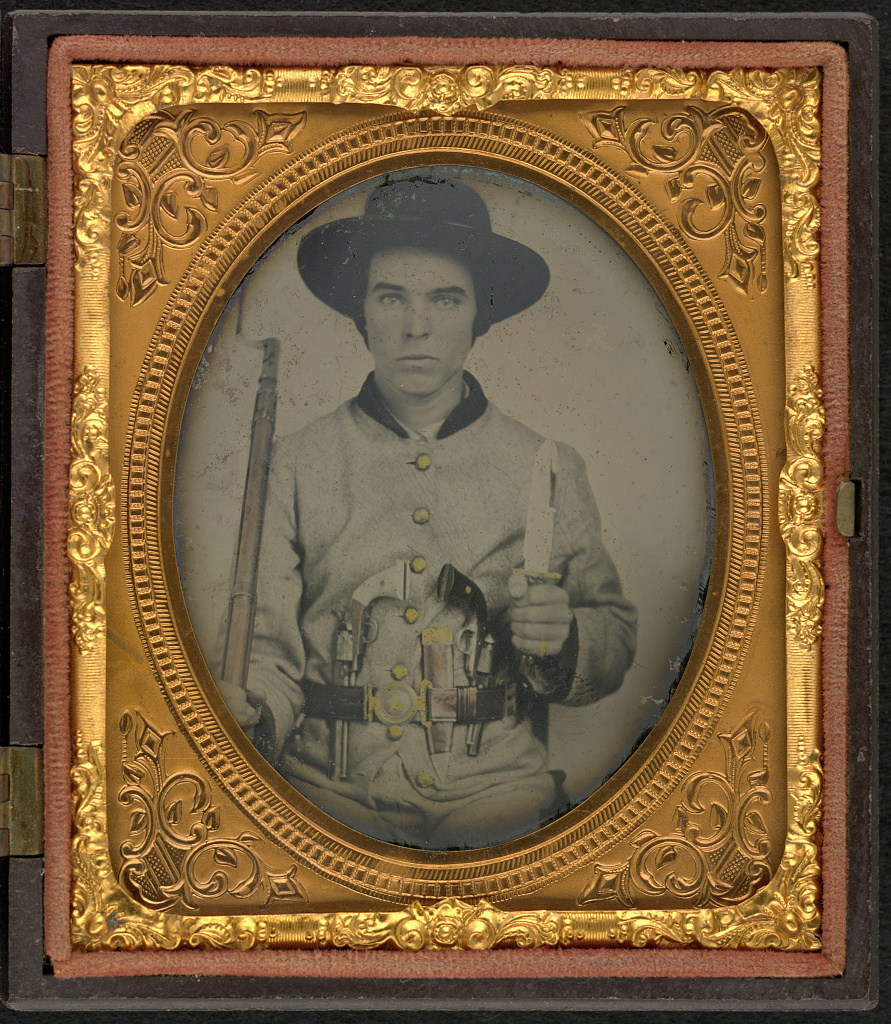

The Civil War brought economic and social instability to the region, though relatively little is known about how the war affected Rusk County. Economic data during the conflict were not precisely recorded. Rusk County was a leading contributor of soldiers to the Civil War—at least 12 Confederate companies mustered there. Among the enlisted men were two of the Hendricks’ grown children, brothers John Stephen and Allen Vince.

Elizabeth Hinton Vinson Ware Flanagan, Levi Hill Ware’s widow, and her second husband James Winwright Flanagan profited from the conflict, since they supplied large quantities of leather under contract to the Confederate government. Flanagan established a tanning yard in Henderson and operated a tannery on the grounds of the Ware plantation, which his wife owned. The Hendricks, on the other hand, seem to have suffered economically during the Civil War. It is not clear whether their economic decline was related to the war, Hendrick Sr.’s loss of a civil suit in 1861, or other circumstances, such as a devastating 1860 drought.

The end of the Civil War brought economic depression across the South. As was true for most Texas property in the immediate aftermath of the war, local land values declined, including the Hendricks’. Like many southerners, Hendrick Sr. filed for bankruptcy, taking advantage of the Bankruptcy Act of 1867, a congressional effort to lessen financial turmoil in the aftermath of the war. The releases from debt resuscitated debtors and equitable distribution of defaulted assets helped creditors. Until the unwieldy and poorly managed act was repealed a decade later, voluntary bankruptcies such as Hendrick Sr.’s were filed at a higher rate in the South than they were across the entire country during the war—counting 31,000 voluntary and involuntary bankruptcies filed in the 11 Confederate states. Because filers were usually white male merchants, professionals, or planters, with Hendrick Sr. ticking two of these three boxes, the act secured and reinforced the structure of southern class hierarchy in the postbellum era. The Bankruptcy Act upheld the economic, political, and social influence of the same men who held power during the antebellum period.

Regional Politics

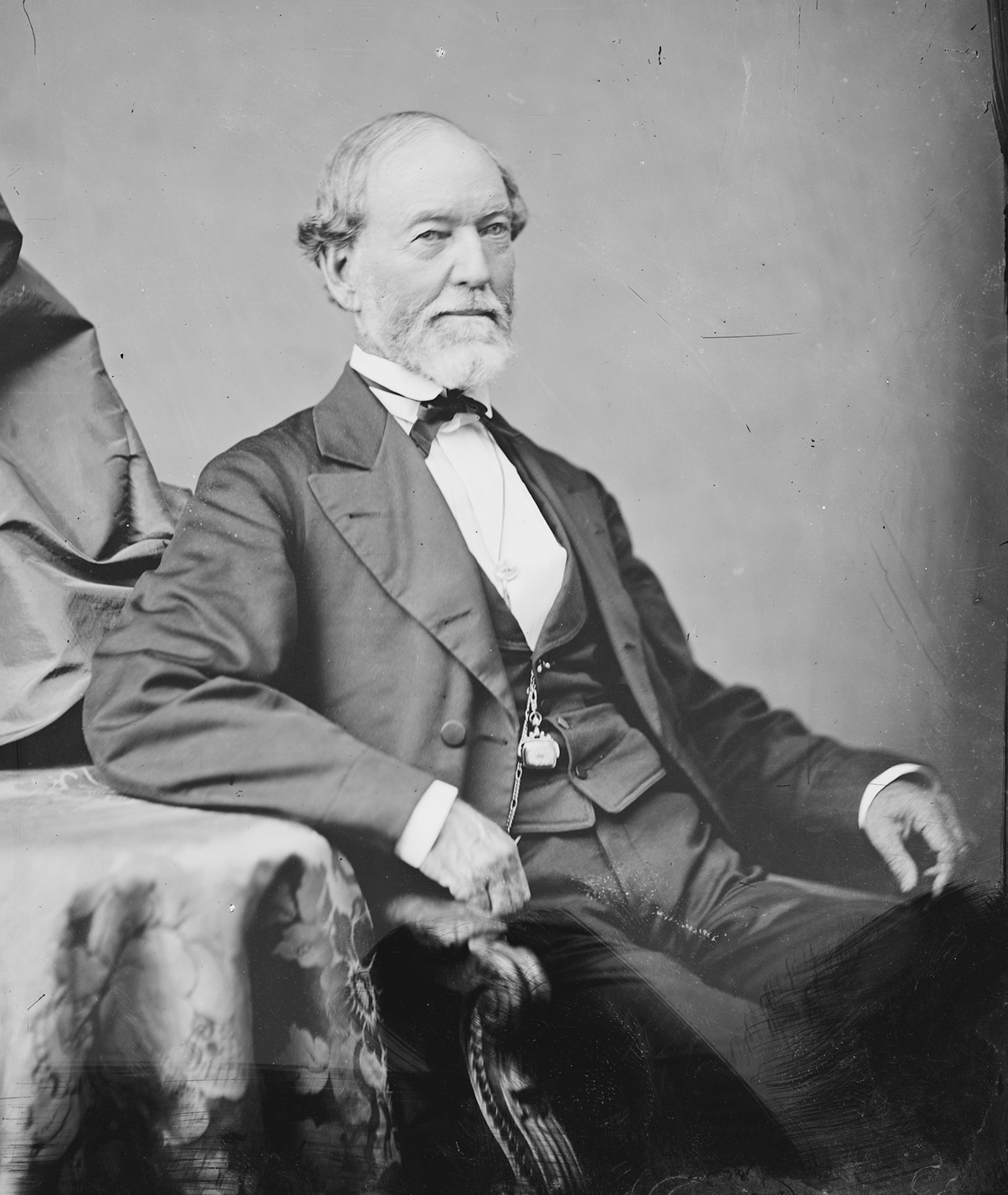

Though little is known about the political identities of the majority of the Ware and Hendrick family members, the political career of Elizabeth Ware’s second husband, James Winwright Flanagan, is well documented. Flanagan was active in politics before and after the Civil War, eventually serving as a U.S. Senator. Here, Flanagan’s career provides an introduction to major political movements before and after the war, and illuminates some of the nuances and complexities of political ideology and practice.

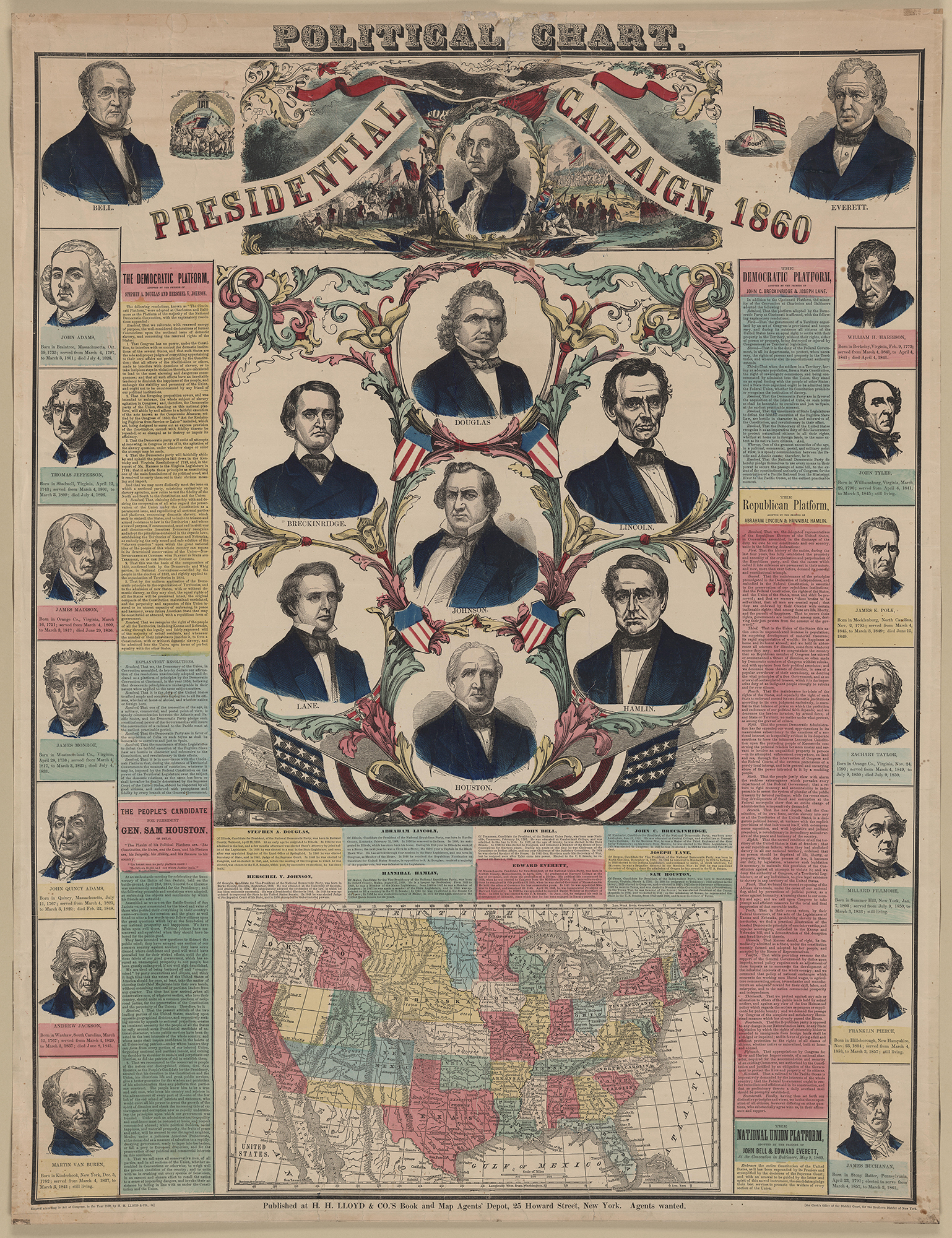

Before his marriage to Elizabeth, James Flanagan was a Whig state representative (1851–1852) and a Know-Nothing state senator (1855–1857). As a Whig and Know-Nothing politician, Flanagan opposed Texas’s secession from the United States. This unionist political stance was widespread among conservative paternalistic slaveowners, notably U.S. Senator Sam Houston. Their allegiance to the federal government linked conventional Southern Whigs of the 1830s with Constitutional Unionists of the late 1850s, holding that secession was anti-democratic and anarchical.

The Whig and Democratic parties were the dominant political factions in the early to mid-nineteenth century. Whigs were optimistic moderates who upheld Protestant middle-class ideals and were typically anti-Catholic and sometimes anti-immigrant. They supported public services such as banking and education, a reflection of their faith in government and hope for a modern America filled with opportunity. Democrats were wary of the quickly industrializing present, and nostalgically embraced the past. Democrats feared they would lose their traditional lifeways if slavery, the labor system they relied upon, was abolished. Democrats valued individuality and believed that governmental control would lead to loss of freedom.

The Whig Party’s demise in the mid-nineteenth century is linked to the acquisition of western territories by the United States. Following the annexation of Texas and the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, Mexico seceded western territories to the United States in 1848. The acquisition of these expansive territories, future states, brought the issue of slavery and whether western states were to permit it, to a head. The Whig Party did not have a clear stance on slavery; party members included both slaveowners like Flanagan and those who saw slavery as irreconcilable to the spirit of freedom. Under pressure to choose a side, the Whig Party collapsed.

Several political movements emerged from the ashes of the Whig Party. These included the Republican Party, the American Party—which included the Know-Nothing faction that Flanagan joined—and later, the Constitutional Union Party. The Republican Party took a firm stance against the expansion of slavery and garnered support in the northern, free states. The American Party and the later Constitutional Union Party maintained relatively neutral stances on slavery and were more popular in the southern United States. Like the Whigs, the American Party united behind an anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic platform. The Constitutional Unionists sought literal and strict interpretations of the Constitution. Both the short-lived American and Constitutional Union parties opposed secession. The Republican Party became the reigning opposition to the Democrats after the 1860 election of Republican, and former Whig, Abraham Lincoln to the presidency.

Locally, Flanagan did not hold political office during the war, though he did indicate southern allegiance through his sale of leather to the Confederate government. After the Civil War, Flanagan resumed his political career, running as a Radical Republican. The Radical Republicans were a party faction that sought to abolish slavery and immediately integrate freedmen into free society. As a Radical Republican, Flanagan was a delegate to the Texas constitutional convention in 1866 and 1868–1869, the Lieutenant Governor from 1869–1870, and a U.S. Senator from 1871 to 1875. Given that Flanagan was, during the antebellum period and throughout the Civil War, a slaveowner, his affiliation with the Radical Republicans is surprising. History characterizes Flanagan as an insincere superficial radical, content to restore ex-rebels without concern for freedmen. His sarcasm on the Senate floor drew laughs from the gallery in January 1872, when he disclosed that he had tired of civil rights and hoped “to get rid of this matter,” according to historian Philip Avilo Jr. The Galveston Tri-Weekly News portrayed him as a politician who “regards the treasury as the chief end of government, and a fair chance at the same as the only worthy ambition of the official.” Flanagan was a delegate to Republican National Conventions in 1872, 1876, and 1880, implying his party loyalty, but like most of the Texas delegation, he refused to include freedmen in plans for reconstruction.