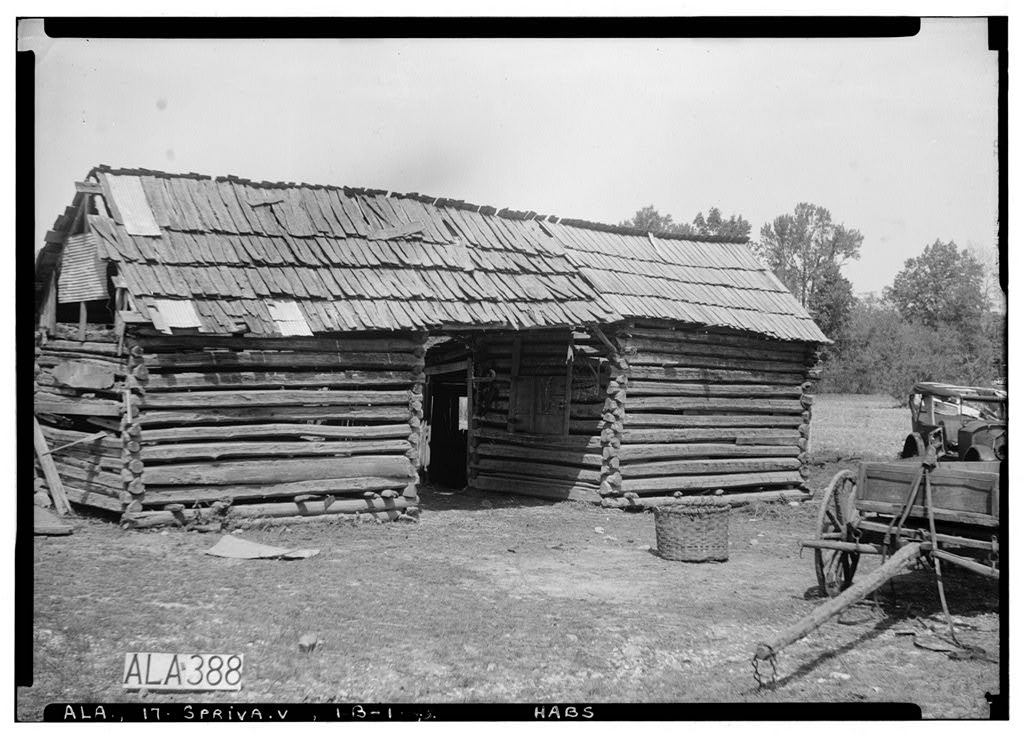

Not that long ago, the Hendrick and Ware plantations were abuzz with activity. Join us as we visit them from the perspective of a horseback rider traveling overland at the end of winter 1863. This journey imaginatively revives plantation life using details from the Ware and Hendrick archeological project coupled with a broad understanding of typical mid-nineteenth-century lifeways. Saddle up!

In the early morning light, the horse and rider navigate navigate Trammel’s Trace, a wagon-rutted dirt road that crosses deeply forested swamplands on the south side of the Sabine River. The long, slender Hendricks Lake emerges on the west side of the road. The lake naturally formed from a section of an old Sabine River channel. On its banks, several people fish for catfish. Over the clop of the horse's hooves, the rider overhears the fishermen discussing the rumor of Spanish silver pirate Jean Lafitte purportedly sunk here in 1816.

Just past the south end of the lake, the rider crosses onto the Hendricks’ property. A road branches southwest toward the Ware plantation, but the rider continues south toward the planter family's house, dwellings of the enslaved, and barn complex. The journey from the lake to the house is just shy of 2 miles and takes the horse about 45 minutes. The horse and rider travel through open oak, hickory, and pine woodlands, before climbing out of the bottomlands of the Sabine River onto undulating sandy uplands. Coming out of the forest just before reaching the Hendricks’ house, the landscape is open—African Americans enslaved by the Hendricks have cleared the woodlands and planted crops in these expansive fields. The rider sees a group of enslaved men, women, and children preparing fields for spring planting. Though it is still morning, they have been laboring for many hours. A young white man, probably 17-year-old Wesley Hendrick, is overseeing their work.

The rider crosses a small drainage before reaching the Hendricks’ one-and-a-half-story log home—the largest building on the plantation. It sits atop a natural rise which, from the rider’s perspective, makes the house appear bigger than it really is. This house is not the kind of grand, pillared mansion stereotypically imagined for a southern plantation. It is constructed of hewn logs and measures about 1,300 square feet, including the front porch and a small one-story rear addition. A fenced yard surrounds the big house complex, which includes a detached kitchen and another small building. The yard is packed bare dirt, which an enslaved woman is sweeping clean as the rider approaches.

The rider dismounts and steps up onto the 8-foot-wide porch extending the full length of the big house. The house sits on brick piers with sandstone footings that elevate its wood-plank floor and front porch 2–3 feet off the ground. The rider is greeted by the eldest Hendrick daughter, Emma, who is 19 years old. Though married, her husband is away fighting for the Confederacy, and she and her young daughter live with her parents. The two eldest Hendrick sons are also fighting in the war. The 1863 Hendrick household consists of Seaborn, Fannie, and seven of their nine children plus their granddaughter. Seaborn’s mother, Martha, lives in a small cabin nearby.

Emma invites the rider inside. As is typical of the period, the house has two rooms. The larger room, with a tall brick fireplace, is the general living space. The fireplace provides heat and evening light but is not used for cooking. The smaller room is the elder Hendricks’ bedroom. Sunlight streams into the house through glass-paned windows—a luxury that many local farm families do not have. Stairs to the upper half-story are in a corner of the main room near the fireplace. This upper room is for storage and provides additional sleeping space, as does the small rear addition.

Seaborn, the family patriarch and a doctor as well as a farmer, is gathering a couple of medicine bottles to take to an ailing neighbor. Fannie is minding their youngest child, four-year-old Julius, who is playing with a children's tea set. This morning, the rest of the Hendrick children are attending lessons in the one-room schoolhouse at the plantation’s south end.

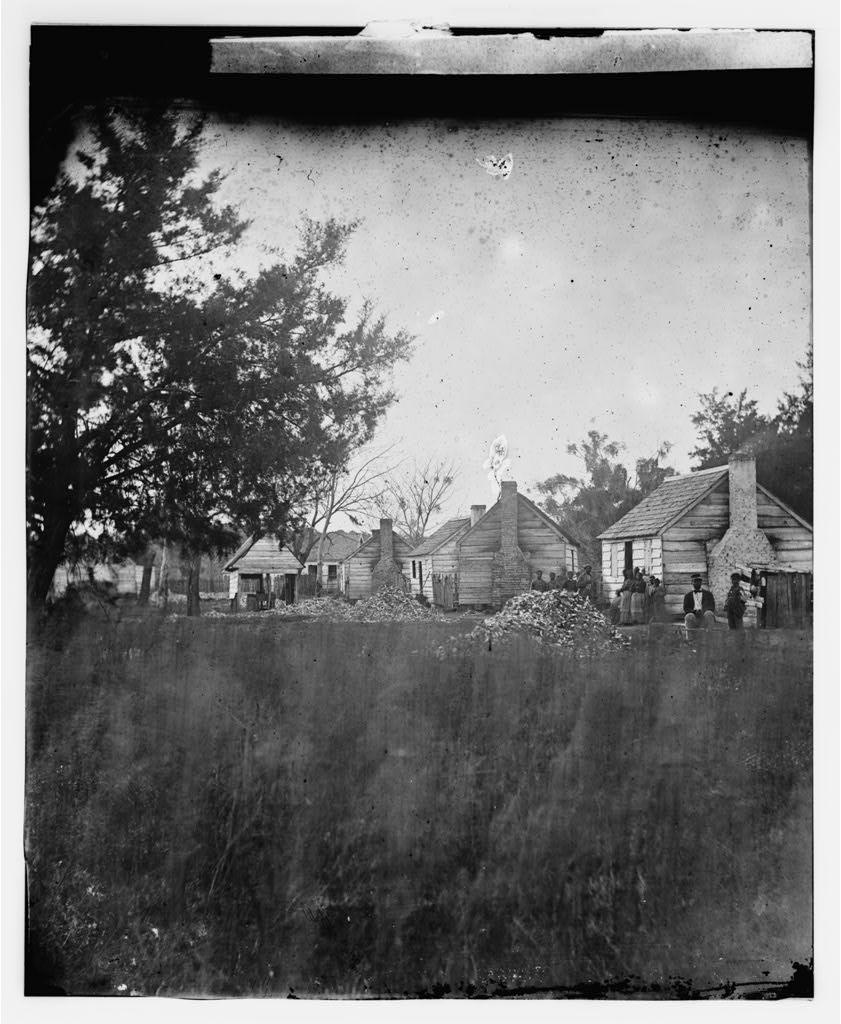

Outside again, the visitor walks about 50 feet from the house to the detached kitchen. The house is safely distant should an unfortunate kitchen fire occur. The log building has a large brick fireplace topped with a mud and log chimney. The cook, an enslaved woman in her late fifties, uses this fireplace to prepare meals for the large family. During this visit, the cook is cleaning after the Hendricks’ breakfast. She pauses to offer the rider some still-warm coffee, and pours herself a cup as well, sweetening both with a little honey.

Next to the kitchen is a shed that likely serves many purposes—additional kitchen workspace, storage, and a smokehouse for processing pork the enslaved workers preserve each fall. Beef provides a large share of the Hendricks' protein, but otherwise they have a typical southern diet, commonly eating pork, corn—fresh and as bread and hominy—occasional wheat bread, honey, fresh and sugar-preserved fruits, coffee and milk or buttermilk to drink, and vegetables such as sweet potatoes, turnips, and field peas.

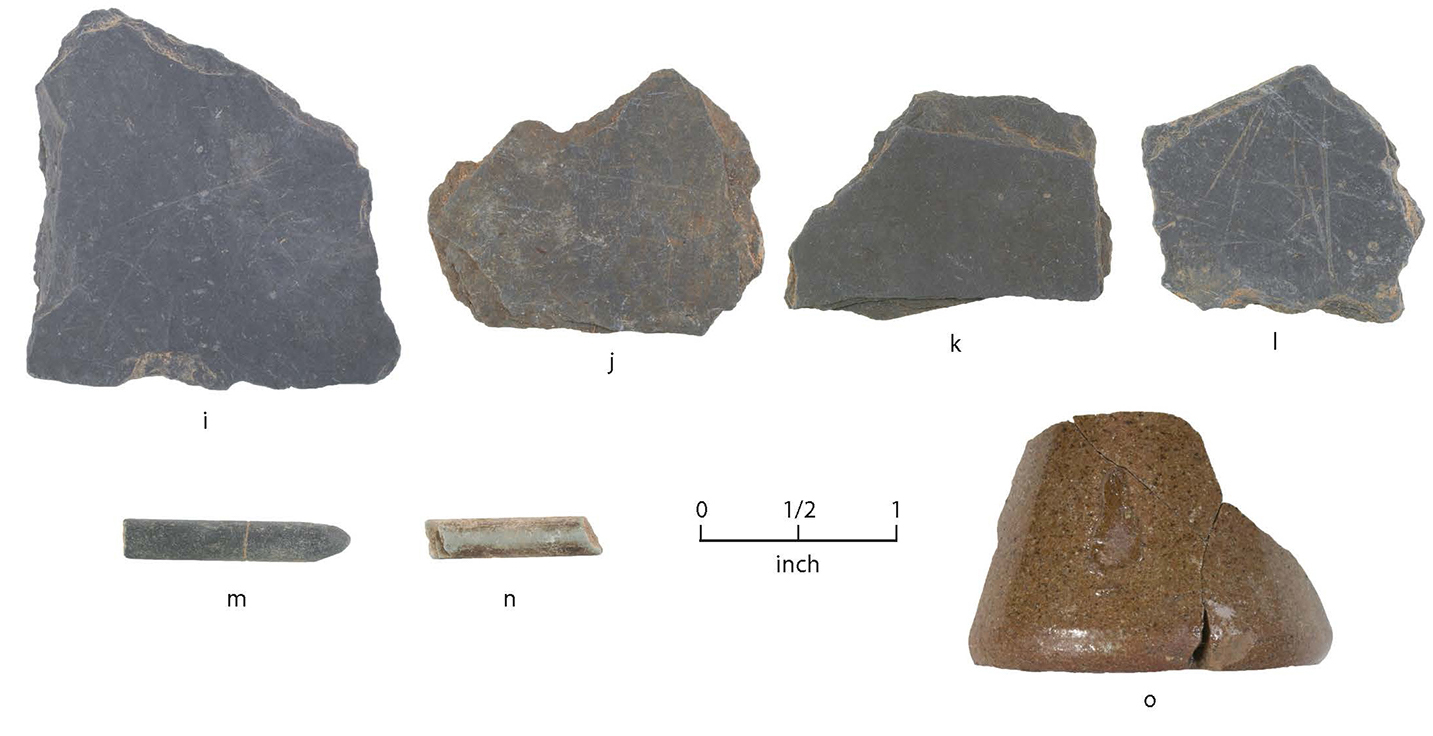

The yard in the vicinity of the kitchen is not swept clean. Instead, fragments of broken ceramic dishes, bottle glass, empty metal cans, butchered bones, and other kitchen implements are scattered across it. With so many activities occurring in the kitchen and adjoining yard area, such as chopping wood, doing laundry, and making soap and candles, it is not surprising this part of the Hendricks' yard is less tidy than others.

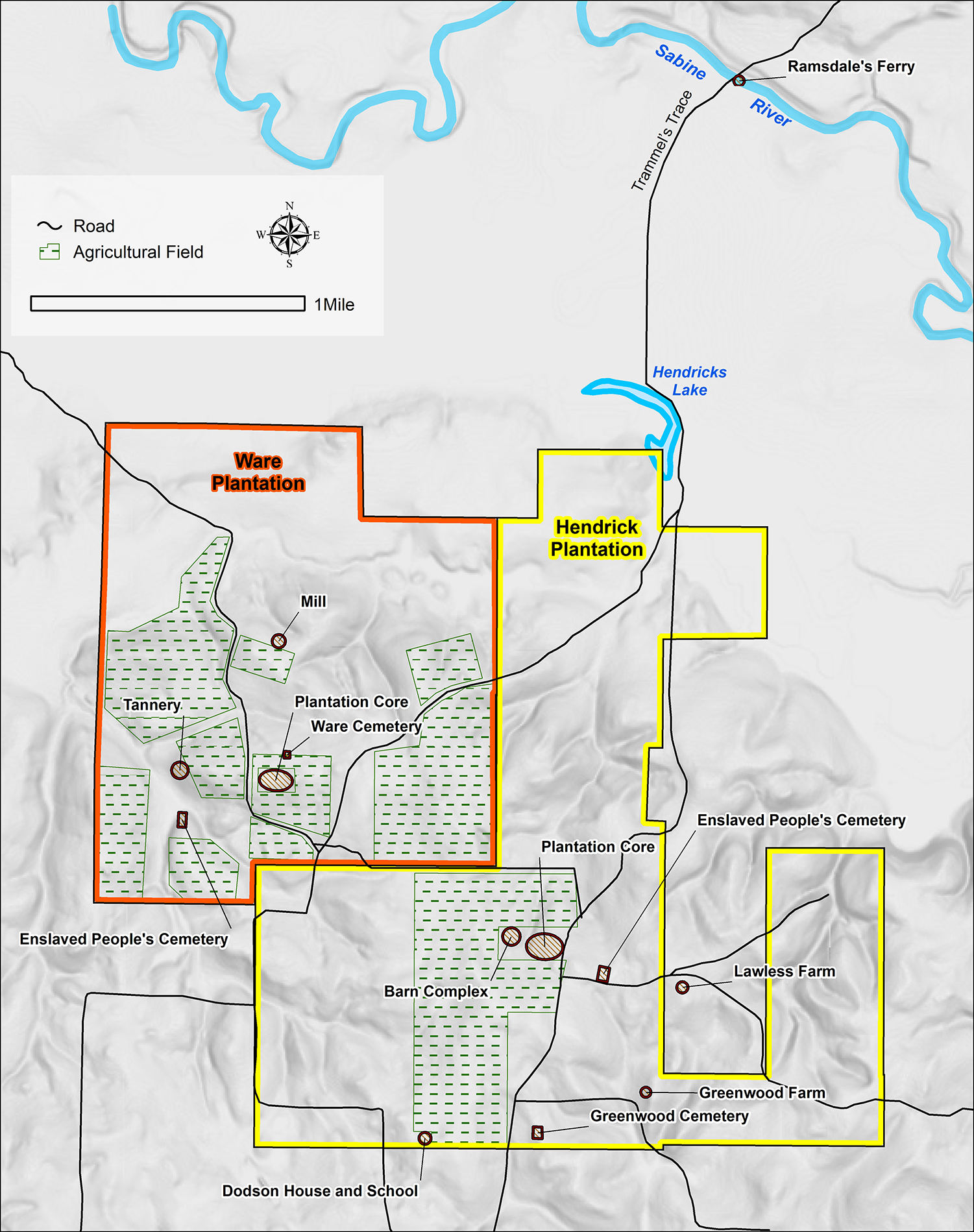

It is a short ride out the backyard gate, past an outbuilding that may have been used as living space in the warm seasons, and down the gentle slope to the slave quarters. Five log cabins arranged in a staggered row are tucked among the trees. The ground beneath most of the cabins slopes steeply towards a spring-fed creek. Each cabin is 250–400 square feet, or 16 to 20 feet on a side, with one or two small glass-paned windows and a wood and mud chimney.

This year, 19 people live here, or about 4 per cabin. At the moment, most of the adults and older children are laboring in the fields or at the big house. The visitor peers into the window of a vacant cabin and sees the dark room crowded with wood-frame beds, storage trunks, other furniture, mismatched dishes, cookware and storage crocks, an oil lamp, and an andiron stacked with firewood.

A mouth harp, tobacco pipe, pencil and paper,

and children’s marbles sit atop a table, attesting

to occupants’ leisure-time pursuits.

The sounds of children’s voices come from the furthest cabin in the row. The visitor rides towards it and finds several young children and a woman in her teens. She sits in a patch of sunlight, sorting through a dish of buttons with one hand while holding a sewing needle in her mouth. She is mending clothes, some of which are workers' tattered garments, though a few fancier clothing items which may be the Hendricks' are also among them. A child, probably 5 years old, is cutting fabric patches from an irreparable garment while younger children occupy themselves with marbles and homemade toys. The young woman startles upon sight of the rider and knocks over the dish of buttons she was sorting, scattering them in the dirt.

The children watch as the horse and rider make their way towards three other dwellings on slightly higher ground. Two of these are smaller than the slave dwellings but better built with sturdy brick chimneys. The third house is similar in size to the largest slave cabin but has a stone chimney and multiple windows. An older woman—Seaborn’s 73-year-old mother, Ann—has the front door open and is eating a late breakfast inside. She tells the visitor that a young schoolteacher named William Metcalf is living in one of these cabins, and that the third cabin is currently unoccupied, though the kin of a neighbor resided there for a time recently.

Leaving these dwellings, the horse and rider cross above the head of a spring-fed creek where the plantation occupants get water. A complex of agricultural buildings emerges ahead at the edge of a field. Upon arriving at the complex, the rider inspects these small log barns and sheds which contain tools, wagons, a carriage, fodder, and log cribs for storing agricultural products.

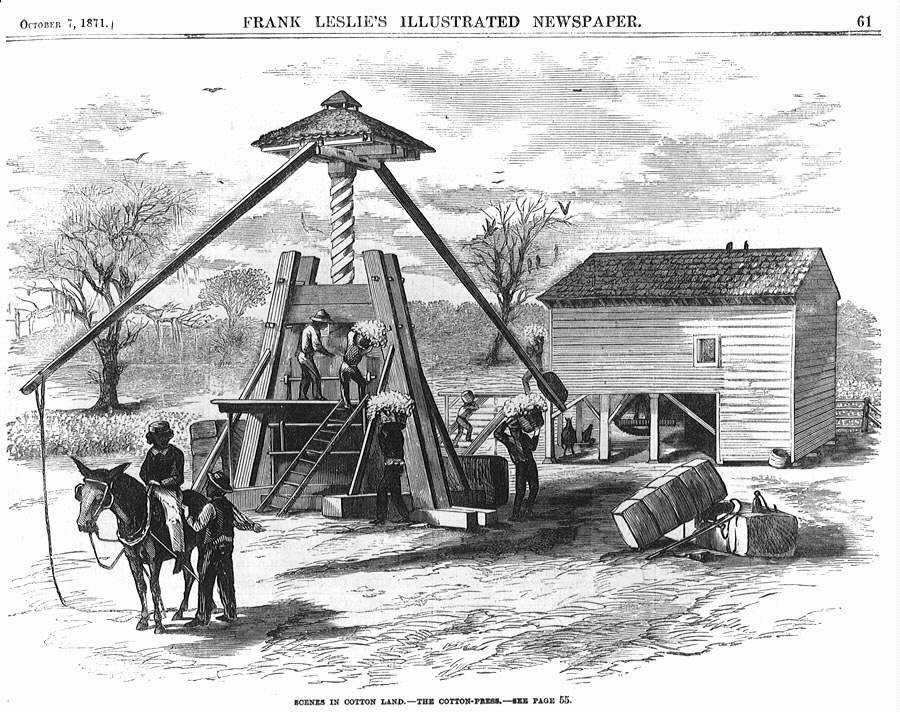

As it is winter, the storage areas are not as full as they will be in late summer and fall. In season, the log cribs are filled with corn, oats, wheat, and rye, and sacks of wool. A root cellar contains sweet potatoes and white potatoes, as well as dried peas, beans, and honey. Nearby are a cotton gin and press, used to separate cotton lint from seeds and compact the lint for baling. Baling is a winter activity, and the Hendrick plantation typically produces about 60 cotton bales, each weighing 400 pounds, which are stored in the barn before being taken to market.

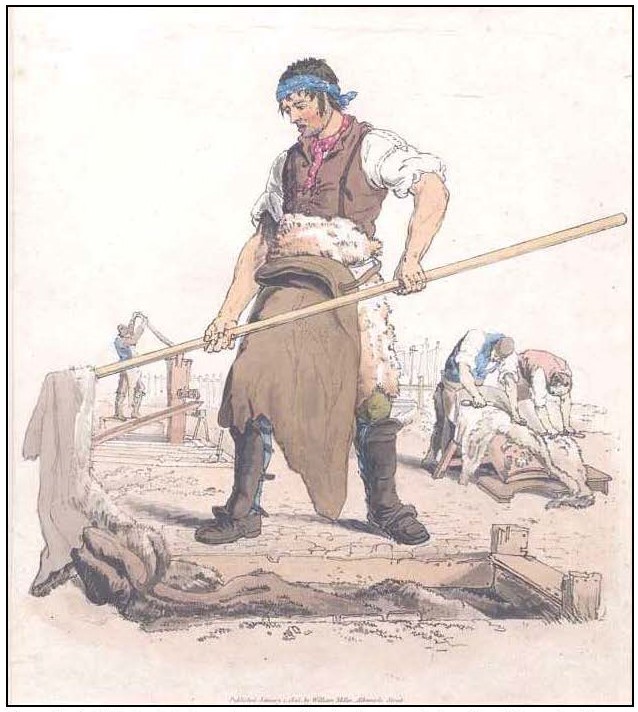

The plantation’s draught animals—4 horses, 7 mules, and 4 oxen—are kept in pens nearby. Most of the plantation’s other livestock—around 100 beef cattle, 100 pigs, 25 sheep, and 25 dairy cows—are rounded up when they need to be doctored, bred, fattened, slaughtered, sheared, or milked. The vast majority of the Hendricks’ property, totaling almost 1,900 acres, is unimproved, so their land is mostly forested. Their many livestock range freely in these woodlands.

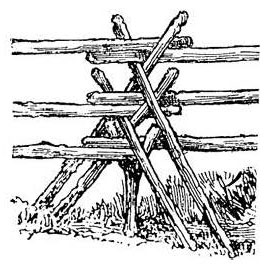

The Hendricks’ expansive 300 acres of improved fields are impressive. Stake-and-rider fences that surround the fields prevent the ranging livestock from damaging crops. The visitor gazes across the growing rows, observing that the enslaved workers have planted them in winter wheat, rye, and oats, which will be harvested in the spring. Some fallow fields await corn and cotton seeds in the coming months.

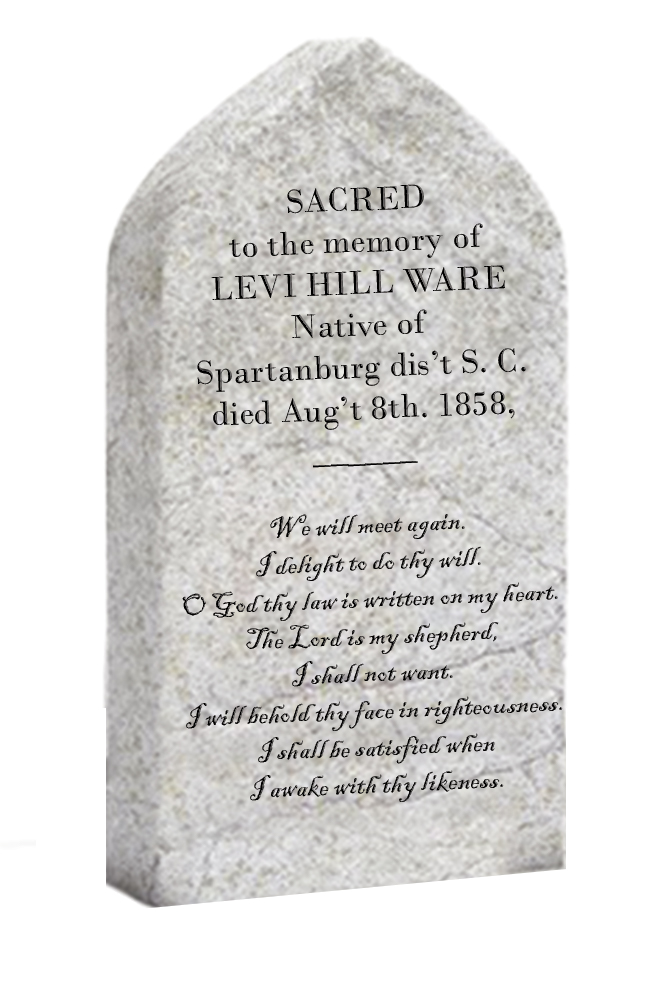

The rider returns to Trammel’s Trace and heads back north, taking the turnoff to the Ware plantation. The trip from the Hendrick house to the big house where the Wares used to live is short, only about 1.75 miles. Levi Hill Ware is dead by this time, and his remarried widow, Elizabeth, has moved to Henderson where she lives with her second husband, James Flanagan. Elizabeth still retains ownership of the plantation, and enslaved workers continue to work the land and raise livestock. The Flanagans established a tannery here that enslaved people operate and a white man oversees. The overseer and his wife,

in their mid-twenties, live on the Ware plantation.

The rider turns onto a small lane that rounds the corner of Hendrick’s large field and extends west along the line between the Hendrick and Ware plantations. After a series of turns, the rider sees the Wares’ big house on a broad hilltop. Like the Hendricks, the Wares have a detached kitchen and a shed behind their house. The rider dismounts on the property and draws water from a well about 4 feet in diameter. Both horse and rider are thirsty from their morning ride. To the south and downslope of the big house complex is a cluster of cabins. Among these is the earliest-built dwelling on the property, constructed in the 1840s by the previous owners, where the Wares likely lived when they first moved to the plantation.

Rather than turning south to this cabin cluster, the rider is drawn to a small family cemetery a few hundred feet north of the house. The graveyard is comprised of two marble headstones fronting brick false crypts. The graves are oriented east-west, with the heads to the west, and the crypts are of slave-made bricks. The smaller crypt stands 10 inches above ground, and marks the grave of an infant, born to Elizabeth and Levi Ware, who died 36 hours after birth in December 1857. Ware’s larger crypt is more than twice the height of his infant son’s with an imposing arched headstone measuring more than 5 feet long and 2 inches thick. Its western face, away from the crypt, is carved with two clasped hands framed in an oval, below which is inscribed "SACRED to the memory of LEVI HILL WARE ..."

The rider remounts and continues north. Cultivated fields are on the west and unimproved land on the east, where cattle are browsing the understory. After travelling a half mile, the rider turns east onto a road leading to the head of a ravine where the Wares built a gristmill. The mill has a supported roof protecting a pair of millstones to grind grain, fed through a hopper above, and a trough beneath to catch the meal or flour. A wood-fired steam engine provides the power to turn the upper mill stone, with the water to create the steam coming from the adjacent spring.

Returning to the main road, the horse and rider turn back south, retracing their steps about a quarter mile and then turning west onto a minor road flanked by cultivated fields. The road terminates at the relatively new tannery, which overlooks a creek. An enslaved man is using water from the creek to clean dirt, blood, and flesh from hides before adding them to vats nearby where they soak and rehydrate for about three days. The tanner explains to the rider that after soaking, the hides will be scraped again and bathed in a strong lime solution to remove the hair. After the lime treatment, they will be steeped to remove the lime, and then worked with hand tools to remove any remaining hairs and last bits of flesh or fat—a process called beaming. An enslaved youth is loading a cart with beamed hides. He tells the rider that the hides are going to Flanagan’s other tanning yard in Henderson, where they will undergo the final steps in the process—soaking in a strong tannin solution, drying, oiling, and sale to the Confederate Army. He says he likes taking the hides to Flanagan's tanning yard in Henderson, as it gives him a rare opportunity to see a family member who works in town.

Returning again to the main road, the rider continues south a short distance, following a narrow but well-worn path through hardwood and pine forest to a small ridge overlooking the confluence of two streams. Here, in a forest clearing, are the graves of African Americans who lived and died on the plantation. These graves do not have fancy marble headstones and brick crypts but instead wood markers fronting linear earth mounds that cap the graves. In 150 years, these markers will have decayed, and the graves will be only shallow depressions, if they are perceivable. The dried leaves that blanket the forest floor have been swept from the graves, indicating recent visitation and care.

Retracing their steps, the horse and rider again bear south. They cross the Ware’s southern property line and enter the southwestern portion of the Hendrick plantation. None of this land is cultivated, and hogs, cattle, and sheep abound. The road follows the west boundary of the Hendrick property for about a mile before jogging east onto the property. The rider comes upon a schoolhouse adjacent to Hendrick’s most southwesterly cultivated field. The school is a log building measuring 20 feet on each side and has a large fireplace. Because the early afternoon is sunny and mild, the door is open and the rider sees about 20 Euro-American children seated in the dirt-floor single-room building. A schoolteacher, the youthful William Metcalf, wraps up the lesson and dismisses the children, who pour out of the schoolhouse door. Though excited to be done with class, they know that the school season, about four months out of the year, will soon be over and the older children will work on their family farms. Some children play in the schoolyard, while others break into groups and begin the journey home. For the Hendrick children attending school, home is shy of a mile—a relatively short walk.

The rider heads east from the schoolhouse and turns south on Trammel’s Trace near Greenwood Cemetery where Obediah Dodson was buried in 1854 and where Martha Ann Baker Hendrick Malone Vince Dodson, Seaborn Sr.’s mother, would be laid to rest upon her death some years later in 1869. Soon after, the rider crosses the Hendricks’ southern boundary and passes through the Tatum plantation, where a turn to the right down the Henderson–Grand Bluff Road takes the traveler past several medium-sized farms to the community of Harmony Hill.

Harmony Hill is a relatively new town, established just eight years prior. It is the commercial and social center closest to the Hendrick house, about 6 miles away, and most easily accessed by established roads without rivers or major streams to cross, as opposed to Camden. Harmony Hill is a logical place to which the Hendricks, Wares, and our traveler, gravitate. The main road through town, Henderson Street, is lined with homes and mercantile stores, a grocery, a hotel, and tradesmen’s shops, including mechanics, a blacksmith, a wagoner, a miller, a hatter, and a gunsmith. It is here, on the streets of Harmony Hill, that we depart from our horse and rider, through whose eyes we have glimpsed the landscape, people, and everyday life on the Ware and Hendrick plantations.